December 18, 2024

The Politics of Adobe Architecture

Looking at Adobe

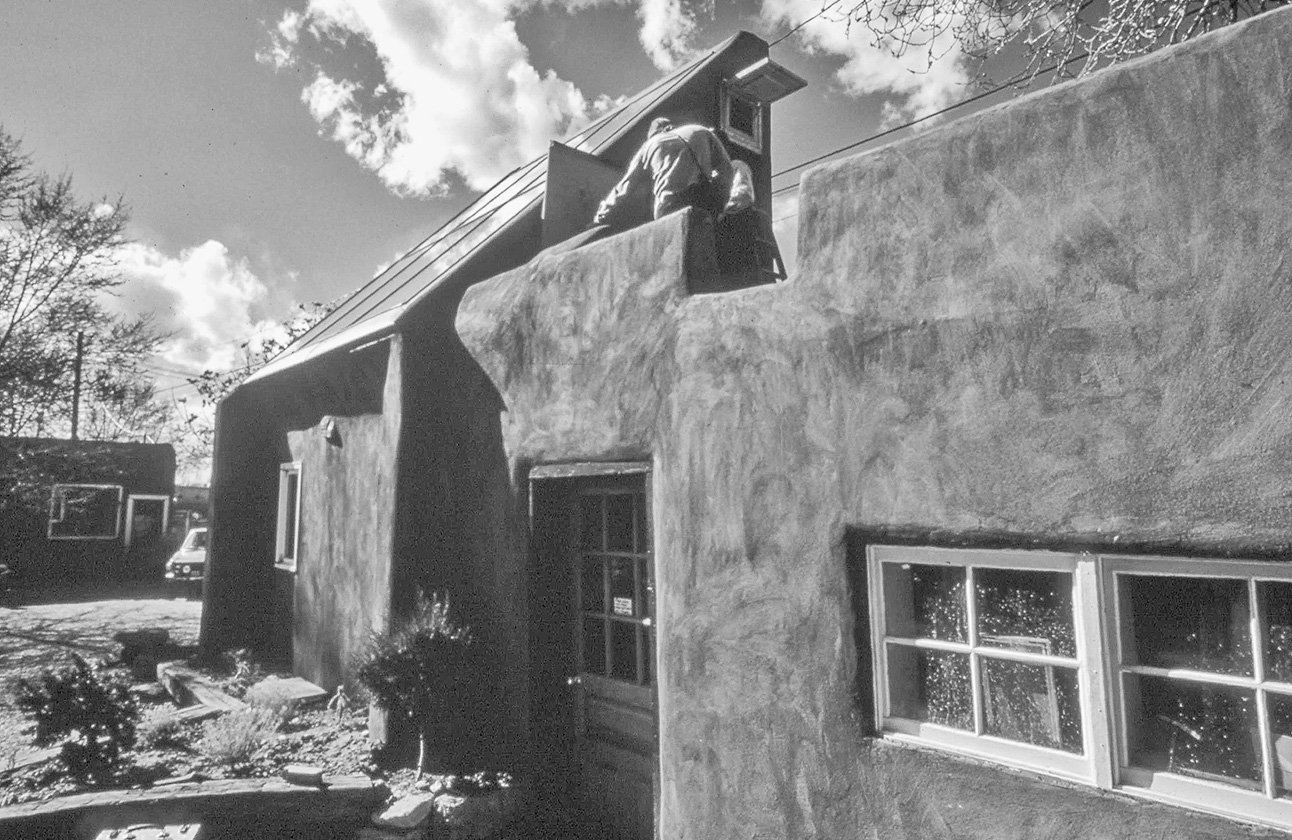

While adobe construction has been used in the Americas for thousands of years, Narath’s term “solar adobe” refers to the unique energy discourse that surrounded the material in the Southwest (specifically New Mexico) throughout the 1970s. The first chapter of the book, “Mud Machines,” situates this discourse within the self-build and “appropriate technologies” movements by analyzing Unit 1, a 1976 adobe and glass home designed by architect William Lumpkins for First Village. A 40-acre community outside Santa Fe, First Village was funded in 1973 by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and was advertised as the “first planned environmental community.” Conceived as a project that would show the potential of solar energy and earthen construction as a response to the oil crisis, Unit 1 was the focus of many exhibitions and national magazine articles, as well as large-scale studies of passive solar heating by research organizations such as the Solar Group at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

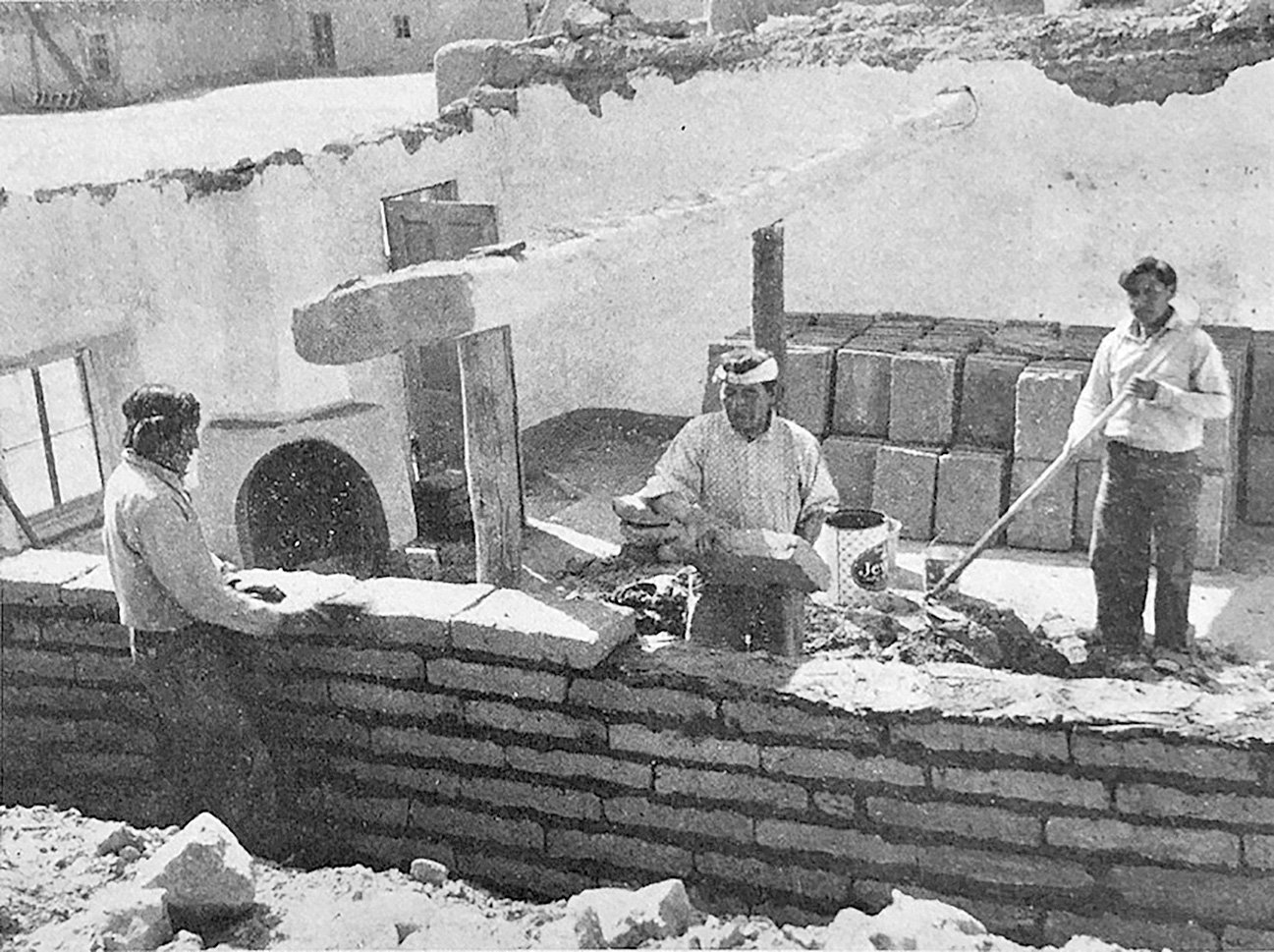

At the time, Lumpkins was a well-established architect in California and New Mexico, where through hundreds of projects he had honed the construction of what he described as “instant old houses.” These “Spanish-Pueblo compositions” were the product of revivalist fantasies, writes Narath.

“Before the adobe was plastered over, construction workers used double-bladed axes to chop windows, door openings, and corners into concave and convex forms in order to simulate the sculptural contours of a long-weathered earthen building.”

There’s a statistic floating around that up to 25 percent of the world’s population lives in homes made of earth. Yet for so many, it’s hard to imagine living in mud. Narath’s book illustrates how people who didn’t grow up in earthen homes look at adobe homes, imagine earthen architecture, fantasize about pueblo communities, and capture raw earth— with their cameras or bulldozers.

Toward Indigenous Planning

In 1974, HUD cited the architecture of Taos Pueblo as a precedent for housing programs in American cities, stating in an issue of HUD Challenge magazine: “Unruffled by the Industrial Revolution and the space age, Taos is a classic example of low-income multifamily housing in its purest form, financed through sweat equity and subsidized by Mother Nature.” Ironically, at the time of publishing, HUD had been actively threatening Native communities with wood frame and concrete block housing developments since the mid-1960s. Narath points out that these government-sponsored housing programs damaged the Pueblo-built environment more than anything else.

His last chapter positions this complicated history of adobe experimentation in New Mexico against a body of work emerging simultaneously among Native scholars, designers, and preservationists—most notably Indigenous planner and Isleta Pueblo member Theodore Jojola, who wrote in METROPOLIS in 2021: “In the Pueblo context, the term ‘architecture’ embodies more than a building’s form, function, and decoration. Architecture does not stand separate from other landscape elements around it.”

Since his experience as a student in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning program in 1974, Jojola has been challenging the environmental and political forces—employment, property ownership, access to education and transportation, and resource development—that were rapidly transforming his and nearby Pueblo communities. Employing personal observation, oral histories, and lived experience (methodologies glaringly missing from the likes of Lumpkins and Scully), Jojola’s documentation conveys not just the HUD unit’s technical failures but also the government’s disregard for local tribal cultures in favor of complete assimilation into the “American mainstream.”

Soon after graduating from MIT, Jojola began teaching at the University of New Mexico, serving as the director of Native American studies from 1980 to 1996; later he founded the Indigenous Design + Planning Institute in 2011, an initiative formed to foster sustainable communities among Indigenous populations.

Learning from Adobe Architecture

“Outside of earthen construction circles, solar adobe is largely forgotten,” Narath concludes. Yet despite solar adobe’s difficulty in finding a place in modern architecture and architectural academia, adobe construction continues today. Solar Adobe comes at a time when contemporary uses of earth architecture are becoming more frequent, as the projects (p. 92) and products (p. 100) in this issue illustrate.

More and more academic initiatives, such as Columbia’s Natural Materials Lab and Yale’s Center for Ecosystems + Architecture, are investigating the environmental and cultural impact of biobased materials and their life cycles. Architects like Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello are experimenting with 3D-printing Indigenous building materials. TV shows like Nathan Fielder’s The Curse are highlighting the inequities of gentrifying passive house building practices in New Mexico Pueblo communities. Even the Museum of Modern Art attempted to grapple, albeit unconvincingly, with modern architecture’s relationship with counterculture and ecology in its recent show Emerging Ecologies.

Perhaps most important, Narath’s research reflects a critical shift in the way materials are researched and discussed in architectural history.

“Thinking about materials foregrounds the uneven dynamics of the extracted and consumed, raw and refined, and visible and invisible that have come to structure the movement and manipulation of building materials, as well as the trails of pollution, cleanup zones, and living communities that often lay in their wake, under capitalism,” he writes. “One of the clearest goals of solar adobe was to collapse the distance between extraction and consumption.” It’s painfully apparent that we still have a lot more to learn from the simple, time-tested adobe wall.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

Inside METROPOLIS’s Sustainability Lab at NeoCon

Discover tools, ideas, and inspiration to make thoughtful material choices for a sustainable future.

Projects

Storm King Takes the Parking out of Sculpture Park

Storm King Art Center’s Capital Project has completely transformed its parking, visitor pavilions, and grounds for a more accessible—and less car-centric—outdoor art experience.