May 16, 2016

The Remarkable Story of the SCAD Museum of Art

In 1991, Paula Wallace saved the U.S.’s oldest existing railroad complex from demolition—and embarked on a remarkable 20-year journey.

SCAD Museum of Art

All images courtesy of SCAD

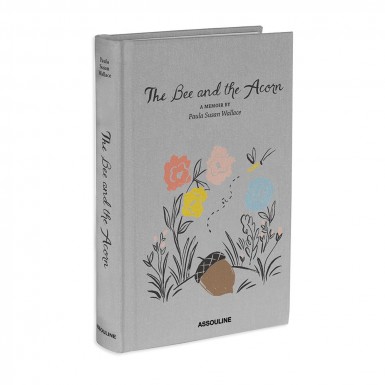

The following is taken from The Bee and the Acorn, the memoir written by the president and founder of the Savannah College of Art & Design (SCAD), Paula Susan Wallace. This excerpt, taken from the chapter titled “Lanterns,” tells the delightful origin story of the SCAD Museum of Art and explains how the school became a leader in historic preservation and adaptive reuse.

I just got a strange call,” my assistant said, one day back in 1991. “Something about a building being demolished. The caller wanted you to know.”

This wasn’t uncommon. I’d gotten some unusual calls and letters over the years, from community members concerned about suspicious students outside their homes.

“What are the students doing?” I’d ask.

“They have cameras.”

And I’d have to apologize and break the bad news to them, that maybe the students were engaged in illicit acts of architectural photography. Sometimes, it’d be parents calling about their children.

“I’m just worried,” they’d say. “She doesn’t seem to have any direction.”

“What year is she?” I’d ask. “Has she picked a major yet?”

“She’s seven.”

We’ve gotten more oddball calls about one subject than any other: real estate. Some days, it seemed like everyone on the Eastern Seaboard with or without a real estate license was trying to get us to buy some historic property where General Sherman’s troops had bivouacked. According to tour guides and real estate agents and homeowners, Sherman’s men commandeered nearly every home in Savannah for some purpose.

“This home was a Union hospital,” they’d say.

“Sherman’s troops appropriated this one for a saloon.”

“His chickens roosted in this very carriage house.”

Sometimes the stories were about the Marquis de Lafayette or maybe John and Charles Wesley, but there was always a story. Always.

I suppose it’s normal for people to want some connection to a city’s myths, but I’ve fielded too many crazy calls to believe them all, especially calls about buildings, famous people who lived there, slept there.

“What building were they talking about?” I asked.

“The man said something about a depot,” she said. “Something about some developer who was going to bust it up and sell off all the Savannah gray bricks for one dollar apiece.”

This was the Central of Georgia Railroad Depot, the oldest existing railroad complex in the nation, the beginning and ending of every rail line in America. I decided to go see for myself. Were they really going to raze it?

In the car, across the cobbles of Taylor and Jones Streets, I thought about the sad situation of this property, arguably the most important historic structure in a city full of them. Here was a building where Sherman did more than sleep, as its capture represented the beginning of the end of the rebellion, despite the Confederate soldiers’ setting fire to the depot, not wanting the Union to get their hands on a year’s worth of cotton, bales of it stacked to the sky—although other stories suggested it was the Union soldiers who burned the depot as a warning to Confederate ships in the river. The one common thread in both versions is that the fire was so bright that it was visible for miles out at sea. Some even said they saw it from Bermuda.

Nearly one hundred years before Sherman, one of the bloodiest battles of the Revolutionary War took place on that same ground. If any earth was sacred in the city, this was it.

By 1991, the property’s value was in the much-coveted Savannah gray bricks, fired at Henry McAlpin’s Hermitage Plantation upriver. By the late twentieth century, most of the original antebellum depot—the size of two city blocks—had lost its roof. It was less a historic property than a historic wall. But some wall. I was worried we’d get there and find it gone, nothing there but a wrecking ball in the dirt. I hadn’t thought my life would turn out like this. I’d read my Jane Jacobs, seen firsthand how cities shape the human imagination, how cities are in many ways the greatest of all human creations, the ultimate act of art and design. The university tried to be a good steward through adaptive reuse projects that respect and retain a building’s heritage significance while adding a modern stratum.

For SCAD, education is that modern stratum, the new idea we put into old buildings, just as Jacobs so famously advocated. Across the colonial city of Savannah, the university added new chapters to the stories of its places, and I wondered if we would ever play a role in the story of this depot.

When our car emerged from the trees and turned toward the vast site, though, we saw no flames, no wrecking ball, not a soldier nor an army of hard hats. Just pigeons, and weeds, and the charred walls of the old sheds, hanging on for dear life.

“Maybe it was a prank call,” I said.

…

But it was no prank. I made a few inquiries, got the whole story—about the developer who’d bought an option on the property so he could erect a parking garage. A city needs those, but not on hallowed ground. The actual demolition, I was told, was scheduled for four days later. The destruction of the depot threatened to nullify the National Historic Landmark status of the property, risking a domino effect, where Savannah could lose whole swaths of history, whole districts.

A few calls stopped the wrecking ball, but only for a moment.

We needed this property. I just didn’t know what we would put there.

“We need dorms,” my colleagues in administration said.

“We need an athletics facility,” said others.

Athletics played an important role at SCAD, and yet, what this particular site needed was not tennis courts and bleachers.

Every few months, the property tiptoed up the scaffolding to the hangman’s noose. Injunctions would stop it, then lapse, then more injunctions. SCAD offered to buy the property, with the promise that we’d preserve what was left of it, and the Savannah Morning News announced its support of our efforts: “Clearly,” the editorial board wrote, “the SCAD sale is the best of all possible worlds.”

We prayed, we hoped, and then, with a chorus of defenders across the city, our lower bid was accepted.

Immediately, we did what work we could to stop the deterioration, braced precipitous walls, fenced off the most perilous areas. To get a sense of the immense size of the property, imagine a parcel of land deep enough to hold the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the Louvre. At one end was what they called the old Gray Building, in the Palladian style, six immense Doric columns holding the pediment. We rechristened it Kiah Hall, in honor of educator, artist, civil rights activist, and SCAD trustee Virginia Kiah, and we set about our work. As always, students were brought in to study the restoration process, how to conserve interior ceilings, how to peel back each layer of paint to expose the same bitumen black used to paint the locomotives. Soon, Kiah Hall would house the Earle W. Newton Collection of British American Art and the Shirrel B. Rhoades Collection, donated to the university.

But behind Kiah Hall, where the holy ground was located, we had no idea what to do with that, its forest of wild indigo and broomweed and brick, those titanic Romanesque arches stretching for two city blocks, where trains had once spilled their secrets and where students now sat on the sidewalk staring through at a safe distance, painting, photographing, drawing, capturing the light through the ruins.

We fenced it off, secured it, set ourselves to dreaming about what it could be. Students sketched a thousand sunsets through its empty arches, and a thousand more, generation after generation of ragweed beaten back, and pretty soon, the university had grown up around it, vast new residence halls on one side, the Ex Libris bookstore on another, Eichberg Hall and the SCAD School of Building Arts to the south, Crites Hall and Bergen Hall to the north, where students studied performing arts and photography.

“I think it’s time to do something with the old sheds,” I said to Glenn one day in 2007.

“Like what?” he said. “They’re so long, the space is endless.”

As were the possibilities.

Poetter Hall (the old armory), The Savannah College of Art and Design.

…

We never set out to become one of the world’s leading nonprofits devoted to historic preservation and adaptive reuse. In 1979, we bought the Armory because we didn’t have the money to build something new. But it was beautiful, and it had a history, and we felt like our tiny little school might benefit from living in a place with a good story. That’s how it started. That’s it. No grand scheme.

In the years since, the story of the Armory was joined by more stories, of the nunnery where the sisters who taught Justice Clarence Thomas lived, of the Harmonie Social Club, and a power station, a textiles factory, a public health office, and many private homes and nineteenth-century schoolhouses where SCAD students now take classes year-round. In Atlanta, digital media students study in a former NBC affiliate studio and writing students sit with Colson Whitehead and Margaret Atwood and Augusten Burroughs in Ivy Hall, the oldest Queen Anne-style private residence in the Southeastern United States, now a SCAD writing center. The university thrived in many structures that had originally served altogether different purposes. In Lacoste, we have the boulangerie, where the village’s bread was baked for three centuries. A historic synagogue in Savannah is now the student center, a vaudeville playhouse is now home to the Savannah Film Festival, Savannah’s first department store is now the Jen Library, where students spend their days, and then go home at night to a redesigned midcentury Howard Johnson motel that’s now just one of many SCAD residence halls around the world.

We’d done it all, but we’d never done anything quite like this ancient railroad depot. It was a ruin.

“What should we make here?” Glenn asked, walking the site with me.

“How about a museum?” I said.

…

At about the same time Glenn and I had begun to conceive of a new museum on the site, a SCAD-magic miracle happened. It came in the form of a man named Dr. Walter Evans, a Savannah native who’d become a prominent surgeon in Detroit and one of the world’s foremost collectors of African American artwork, representing more than one hundred fifty years of art history. Walter and his wife, Linda, were friends and confidants to many great artists and writers, from Romare Bearden to Alice Walker.

Walter and Linda had returned to Savannah, and they’d quickly become community leaders, investing in the life of the former West Broad Street corridor where the defunct Central of Georgia railroad complex stood. We sat in my office, and he shared his vision.

“We need a home for the art,” Walter said. He wanted somebody who’d take care of it, who wouldn’t store it away, a place where schoolchildren and students could benefit from hearing and seeing and learning the tales the art could tell. I took Walter to the site, where the walls were all that stood of the old depot.

“What if the work lived here?” I said. “The Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art at the new SCAD Museum of Art.”

He looked long and hard at the ground and then looked up and told me a story. Two slaves from a plantation near Macon, he said, once came to this depot. This was long before the Emancipation Proclamation. But they’d heard about the Declaration of Independence, and they’d made up their minds to seek out a new life and liberty, the pursuit of their own happiness.

“Their names were William and Ellen Craft,” he said. “And they devised a plan. A plan to escape.”

Ellen, fair skinned, would pose as a wealthy white planter, a man, and William would be her valet. Together they would come to Savannah, then board the train heading north to free states. On a winter morning in 1848, Ellen donned homemade pants and green glasses and covered her newly shorn hair with a top hat. She wrapped her arm in a sling to avoid having to sign her name, and to dissuade conversation, she feigned deafness.

“They boarded the Macon train, she in first class, William in the slave car,” he said, “and they arrived right here, right where the platform used to be.”

The Crafts then switched trains and headed north, transcending race, class, even gender on their way to freedom. Walter and I sat down with Bob Jepson, another benevolent, kindhearted, generous university donor, and launched a capital development campaign. We broke ground on a rainy, cold January afternoon in 2010.

“I wish it were a prettier day,” I said to Walter.

“The rain is just making the ground soft,” he said. “So we can get to work.”

…

I had only one person in mind to design the new museum: Christian Sottile. He ran an urban design firm in Savannah with his wife, Amy, whom he met while they were students at SCAD. Christian had created the most important city plans for Savannah since General Oglethorpe conceived of the squares, and he was known around the nation and the world for his passion, his intelligence, and his belief that design should be mindful of history but not enslaved to it. Best of all, he was valedictorian of the SCAD Class of 1997, and earned a Master of Architecture from SCAD. In 2011, I named him dean of the SCAD School of Building Arts.

Christian and I walked the site, talking, while he sketched ideas. I shared my thoughts with him, how we needed a gallery dedicated to alumni artists, and a gallery dedicated to the Evans Collection and African American artists, an experiential gallery, a theater for lectures, a café, studio spaces for the Collaborative Learning Center, a courtyard and outdoor theater, and, of course, classrooms, where students from across disciplines could take advantage of the closeness of the exhibitions.

“The question,” Christian said, touching the ruins with his hand, “is what can all this be? It’s not a depot anymore.”

“And it doesn’t need to be.”

“But these walls, these bricks.”

“Seventy thousand bricks,” I said. “At last count. And I want to use all of them.”

We wanted to do more than build a museum around a few old walls. We wanted to do something civic, something monumental.

What he envisioned was a dialogue of contrasts, where a new concrete structure would rise inside the original perimeter of the historic brick ruins. Where walls were gone or crumbling, smooth concrete surfaces would emerge.

“We’re building a structure that will be a part of the cityscape forever,” he said. “Original materials, new execution. Endings, beginnings.”

We would preserve the ruins as we found them—and start from scratch. A new building with a storied history. The SCAD Museum of Art would become a conversation between past and present.

It took nearly two years. Hard hats were all the rage in those days, when my hair remained in the shape of a construction helmet for weeks at a time. In the tradition of Frank Lloyd Wright, I wanted to cohere the entire design into a single mise-en-scène, from the walls to the stairs to the hardware on the doors. I wanted everything to be designed, considered, thought about.

The SCAD team, led by Glenn and me, consisted of dozens of dedicated staff who stayed busy with the project on winged feet. Christian designed and realized our classrooms, a student lounge, a terrace overlooking a courtyard, the entire space a cathedral of learning, with whiteboards and computer labs and a herculean digital tablet that we designed ourselves. At twelve feet long, it was—at the time—the largest interactive device in the world, at least the largest intended for use by the public, designed for guests to learn more about the museum’s exhibitions and collections.

As historic preservationists say, “The greenest building is the one that’s already built,” but we went even further, by using renewable materials and energy-efficient structural elements, outfitting the museum with low-energy light fixtures, zoned climate control, exterior cooling towers, low-flow plumbing fixtures, and low-emissivity glass. Scattered excess bricks were incorporated into the park-like Alex Townsend Memorial Courtyard, and reclaimed heart pine timber trusses were transformed into acoustical slat walls for the museum theater, surrounding the audience in a cocoon.

It wasn’t just the building that’d be innovative; the programming would be equally unorthodox, especially for an academic museum. We would not try to build huge collections and then raise money just to store the art, keeping it locked away. I listened to my wise and wonderful friend Lorlee Tenenbaum, who advised that we create a mutable space, revolving, fluid, something new every season. The SCAD museum would be open to artists from other countries, with new exhibitions every time visitors returned. It wouldn’t be one museum—it’d be a thousand museums.

“If this place is a dialogue,” I said to Christian, “we need a climax.”

“The high point,” he said.

“A statement.”

“I have some ideas.”

What we needed was a signature structural feature, a memorable architectural element that would be, in and of itself, a work of art. We talked and talked, about the history of the place, what it meant then, what it meant now. We discussed the great fires of 1864, the place as a point of departure for newly freed slaves on Emancipation Day.

“It’s a phoenix,” Christian said. “This structure burns, collapses, is wracked by war and time, and now it has risen, high.”

What he conceived of, in the end, was brilliant—literally.

It was perfect, an eighty-six-foot-tall tower of light, a beacon of balefire to draw visitors from around the world, prismatic, reflecting, absorptive, capturing sunlight during the day and providing a diffuse glow in the evening, marking the entrance to more than eighty thousand new square feet of museum space.

He showed me the sketch.

“I’m calling it a lantern,” he said. “Translucent glass and steel. A tower of light.”

…

SCAD Museum of Art

On opening night, in the fall of 2011, we anticipated a few hundred students, and when we arrived, I was shocked to see lines snaking out both sides of the building, right under the gleaming white lantern.

“How many students are here?” I asked Glenn.

“They stopped counting at twenty-five hundred,” he said.

Inside, the students laughed, smiled, picked their jaws up from the floor, absorbing everything from the work; sculptures and reliefs by Liza Lou; portraits by Kehinde Wiley; a SCAD-commissioned video installation by Bill Viola; another site-specific sculptural installation by Kendall Buster; and selections from the Walter O. Evans Collection of African American Art by Jacob Lawrence, Aaron Douglas, and nearly forty more artists. All night, I overheard bits of jubilant conversation among the students, who couldn’t believe we’d made this for them.

I was swept away in a surge of joyful tears, my hand grabbed by faculty friends who wanted to show me a favorite piece, my arms enveloping Walter, and plenty of high fives from members of the university’s Design Group team, who’d dedicated two years to this sublime work of art and architecture.

The SCAD Museum of Art would go on to be featured on CNN, in magazines and newspapers, the critics swooning, the public raving, the students gasping, and the building receiving accolade after accolade, including the American Institute of Architects’ National Honor Award for Architecture. Christian, too, was honored with the AIA Young Architects Award. In the four years since it opened, tens of thousands of visitors have rejoiced in their experience on this sacred ground. The whole precinct around the museum has seen new life. What was once a ruined plat of careworn desolation is now full of life, students walking to class, back to their rooms, to dream dreams born in these old walls that long ago we raced to rescue.

I still think of the Crafts, their powerfully courageous, creative act of freedom. And I think of the enormous hearts and visions of Savannahians like Walter and Linda and Bob and Alice Jepson and many, many others over the years who have helped make it possible for Savannah to sail proudly into another century by preserving the best of its past, and pushing on toward an even more remarkable future.

Not long ago, Glenn and I were in the car on our way to an exhibition of Oscar de la Renta’s work in the André Leon Talley Gallery, the museum’s lantern shining brightly across the city skyline, and I had to laugh.

To think, someone had wanted to make it a parking garage.

Want to read more? Purchase The Bee and the Acorn here.