October 16, 2020

A City’s Surface Reflects Its Inequities

With the multiplying risks of urban heat and the pandemic, a city’s streets and sidewalks tend to highlight vulnerabilities in urban communities.

Surfaces of all kinds are top of mind these days, so we decided to look at all aspects of them, in these articles, from A to Z. Thinking of surfaces less as a product category and more as a framework, we use them as a lens for understanding the designed environment. Surfaces are sites of materials innovation, outlets for technology and science, and embodiments of standards around health and sustainability, as well as a medium for artists and researchers to explore political questions.

Few parts of our urban environment feel more inevitable than the paving of our streets and sidewalks, those transitory spaces whose omnipresence helps them escape the more acute criticism commonly directed toward buildings and parks. But with global warming advancing apace and millions of urban dwellers experiencing more and hotter hot days, a city’s surface is increasingly seen as a site of inequity—one whose health effects the pandemic has sharpened.

Heat waves posed an augmented challenge this summer, as indoor spaces such as malls, movie theaters, and cooling centers became difficult or impossible to use because of the dictates of physical distancing.

For already overexposed and underserved urban communities, these “compounding vulnerabilities,” so dubbed in a recent discussion hosted by the Global Resilient Cities Network with Columbia University’s Center for Resilient Cities and Landscapes (CRCL), are nothing new.

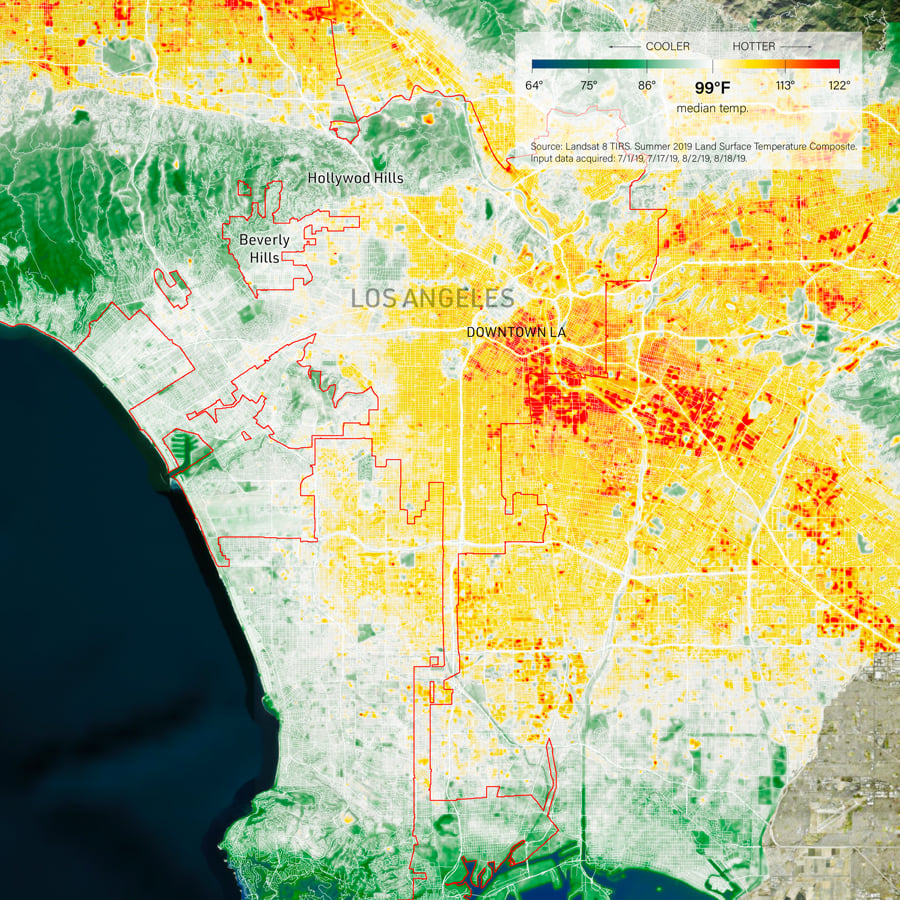

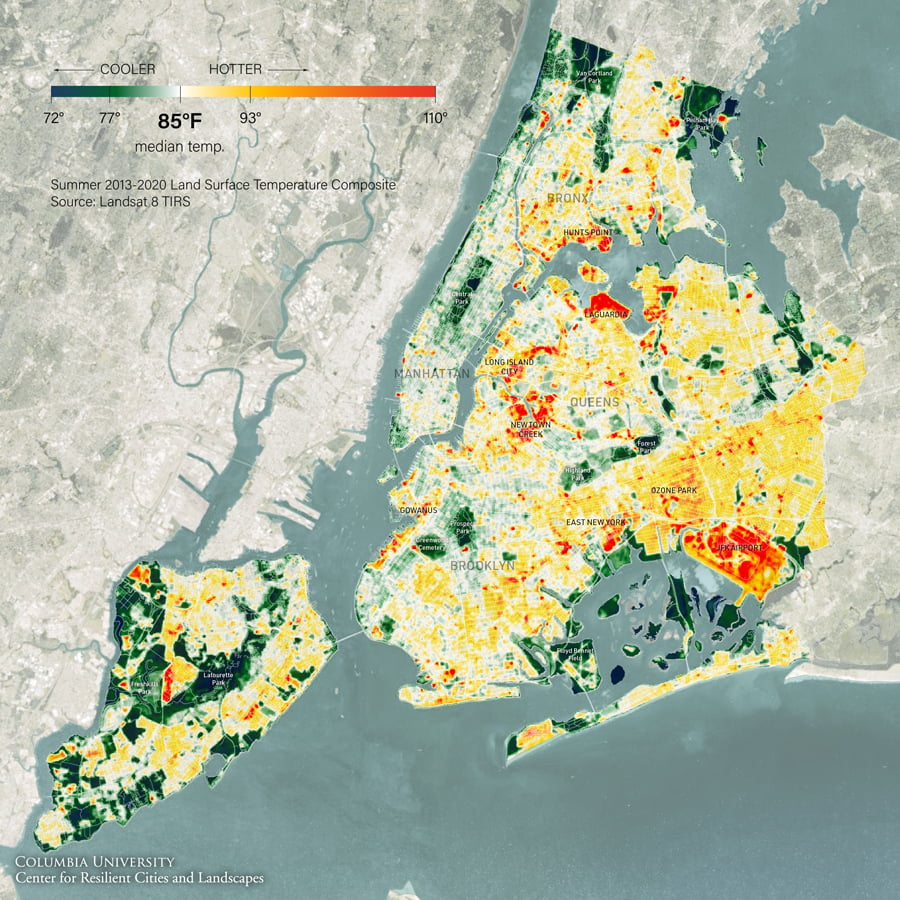

In fact, heat can be seen as a spatial proxy or indicator of social inequity: Areas historically neglected, or even targeted, by planning are particularly vulnerable to the urban heat island effect. Grga Basic, a researcher at the CRCL, adduced the examples of Los Angeles, where 1930s redlining patterns map neatly onto a contemporary thermal map of the city, and Tel Aviv, whose Bauhaus center enjoys cooler temperatures than its socially marginalized and markedly less shaded periphery. (Though data from the pandemic is spotty, Basic further indicates an overlap of heat exposure and fatalities in Brooklyn neighborhoods.)

Surface-level adjustments to urban heat islands are possible through greening a city’s paved and impervious forms. (Landscape firm Djao-Rakitine, for example, has developed movable “lawn typologies” for Paris.) Painting surfaces in lighter colors can repel heat absorption, but within limits—colorful paint can increase glare. Ultimately, urban heat must be viewed not as an isolated, sited problem, but instead in the context of inequitable patterns of urbanization. In this regard, access to cool streets is far from inevitable; regrettably, in Basic’s words, its distribution is “logical and entirely expected.”

You may also enjoy “For Thomas Woltz, Soil Is the Most Important Surface There Is”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025