August 2, 2018

CCA Exhibition Expertly Showcases the Radical Italian Architecture Movement

The rich legacy of “radical” Italian design risks overexposure, but the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s exhibit on the movement’s protagonists avoids the genre’s clichés.

A throng of protesting students—architecture students, in fact—escort the Pop equivalent of a golden calf through the center of Florence. This incomprehensible thing, a large vacuum-inflated polyethylene tube bent back over itself in the shape of an S and plastered with nonsensical text and effigies, trundles along past the Palazzo Vecchio and the dummy David at its base. Outside the Duomo, it cuts through the thicket of tourists, who recoil in bemusement, unable to decipher the scrambled messaging. The profile of the inflatable changes, going from rigid to limp and leaking air, as it bobs in and out of view.

This was the last of a series of aesthetic disturbances to befall the city in 1968, when students occupied the Faculty of Architecture for three months. It was a variation on what could be termed a “design happening”—protest as spectacle. The implements were the Urboeffimeri, or “urban ephemeral objects,” devised by the collective UFO. Last year, this particular Urboeffimero was reproduced and hung in the courtyard of the Palazzo Strozzi, its inscrutability now tempered by the museum setting.

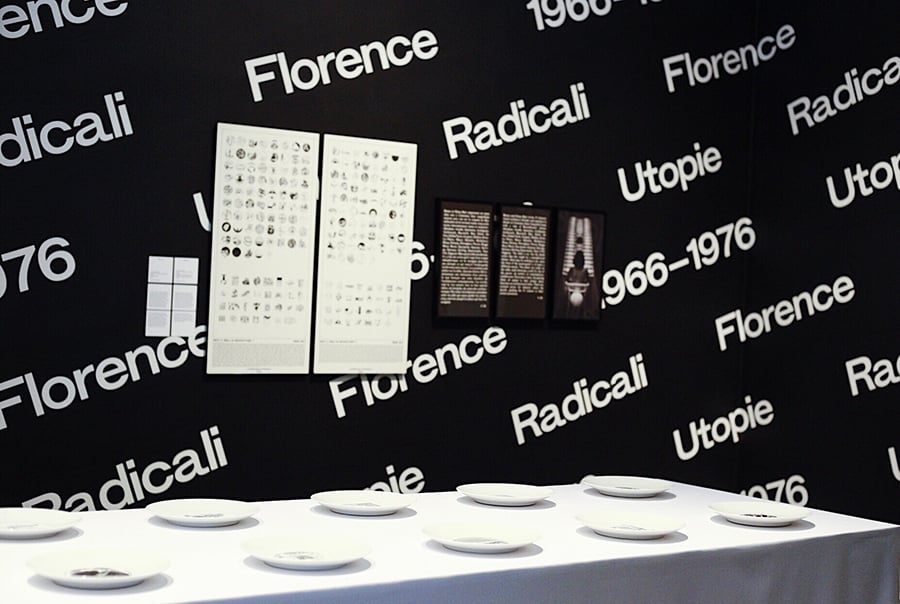

The re-creation was pegged to the exhibition Utopie Radicali: Florence 1966–1976, which commemorated the so-called Radical Architecture movement that flourished in Italy half a century ago, appearing first in Florence before spreading to other urban centers. It has now arrived, in a slightly rejiggered format (and minus its inflatable avatar), at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA). The change of context—from the arch-Renaissance Palazzo Strozzi to the CCA’s Postmodern edifice in Montreal—has to be noted, but does not detract from this enjoyable show.

The exhibition arrives at the low end (one thinks) of a revival of “radical design,” a crusade that had its beginnings in the political ferment of 1960s Italy. The works of iconoclasts like Archizoom, Superstudio, and UFO were cathectic responses to social contradictions that, at least at the time, seemed surmountable. These actions were perhaps meager, metaphorical contributions in the grand scheme of things, but by casting doubt on the meaning and value of architectural labor, this disaffected group aimed to reconceive its own role within society. To paraphrase an art critic from the time, these were architects actively on strike.

But it wasn’t to last. The writing was on the wall by 1972, with the opening of MoMA’s Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, a circus seen by many to be the tombstone of the “radical.” The moniker had not been coterminous with the early stirrings in 1966, when Superstudio opened its “Superarchitettura” installation, appearing one month after the catastrophic flooding of the Arno River. In fact, radicale was improvised years later, in 1970. By then, many of the protagonists—there are seven in the show (Superstudio, Archizoom, UFO, Grupo 9999, Gianni Pettena, Remo Buti, and Zziggurat)—had already begun their transition to industrial designers for hire. Even before The New Domestic Landscape, which paired architects with Italian brands like Artemide and Kartell, the group had gotten a taste of factory production through a number of collaborations with the manufacturer Poltronova—a crossover engineered by Ettore Sottsass, who dropped in on the scene from time to time like a benevolent uncle or druggy guidance counselor.

The designs spawned from this union of Industry, Marxists, activists, semioticians, alt-professors, eco-nihilists, and longhairs have become cult objects. That outlandish works such as Archizoom’s sordid Safari conversation pit (1968) or UFO’s Lampara Dollaro (1969; both are displayed at the CCA) have gained currency among our overlords is unsurprising. The Greek billionaire Dakis Joannou has amassed a collection of the stuff; in an effort to show off his loot, he enlisted the dubious talents of artist Maurizio Cattelan to photograph them. (Cattelan’s cheap juxtapositions of the furnishings, spit-shined to a sparkly gleam, and wanton female form were published in 1968: Radical Italian Design.)

The irony should not be overstated. Ugliness and discomfort were traits sought after by the radicals, who saw their points of intervention unfolding across urban and domestic spheres; the CCA’s adaptation expands these categories, establishing a more nuanced reading of macro/micro. In the Azione section are UFO’s Urboeffimeri and Gianni Pettena’s politicized appropriations of everyday urban life—in one infamous case, a laundry hanging—the idea being to foreground the individual in homogenized mass society. In the gallery devoted to the city, or Città, Zziggurat’s improbable tender for a Florentine megastructure, just grazing the Basilica di Santa Croce, attempts a taller order, imposing modernity on a city where “modernity was substantially extraneous,” as Archizoom member Andrea Branzi has put it.

The intimate scale of the home, however, required a different tack. Members of Superstudio speculated that one might infiltrate this domain by deploying “objects with the greatest possible number of sensory properties,” thus prompting their putative “users” to question the constitutive conditions of their little cocoon. This critical awareness, moreover, might “inspire action.”

To what end? To revolution, perhaps, or merely dancing. Many of the radicals chased utopia on the dance floor, as evidenced in the exhibition’s Disco section. (The show explores eight categories in total, ranging from “territory” to the “body.”) Alessandro Poli’s scale model for a speculative amusement structure, developed in 1966, illustrates the more constructive end of the nightclub imaginary. But for the most part, groups such as 9999 emphasized the atectonic. A collective of self-described “terrible architects” without any clients, 9999 set up the infamous Space Electronic disco as a way to earn some much-needed lira. Part of the pull was the immediacy of the experience, of unalienated human contact—but also the sense of opportunity seized and fate overturned, of space activated. As 9999 asked, “Why do we think that space is not made by sounds and perfumes or by the dark like light is?” Again, inscrutability was part and parcel of Radical Architecture.

Around this time, Adolfo Natalini, the founder of Superstudio, declared in a lecture at the Architectural Association in London that “we”—the designers, students, the man on the street?—“can live without architecture.” And, as it turns out, without design, too. Anticonsumerism was a common thread among the Florentines, who took cues from the American counterculture and Pop Art’s ironies. But this guiding impulse—the “destruction of the object”—was manifested in wildly divergent ways. Where 9999 called for the cessation of commodity production and the rewilding of Florence, Superstudio imagined a gridded energy field that traversed the earth, extending into outer space; architecture would be replaced by life-sustaining technologies. Archizoom devised not only its own utopia—an infinite interior, air-conditioned and devoid of content—but a series of garments to go with it.

These weren’t all flippant artistic acts. The ideas expressed by these (anti-) designs were creative exaggerations of contingencies of political theory. Insurgency had been brewing among the working classes with the denouement of Italy’s Miracolo Economico, the name given to the decades of development induced by the Marshall Plan. Factories sprang up all over northern Italy, where capital was concentrated, and labor flowed up from the south. The result was a massive wave of internal migration without redistribution of wealth. Peasant traditions, cultivated over millennia, were crushed under the foot of this progress.

The radicals delighted in disrupting Modernism’s positivist narratives. As participants on the left, they did not accept the superordination of production over consumption, or economics over politics. They criticized the rationalizing omnibus of technology while also self-consciously indulging in technological fantasias; even with an eye to the lunar landing, they limned alternative futures that incorporated aspects of unalienated rural life. Eventually, like their comrades and rivals alike, they would burn out on politics, and the “movement” fizzled.

Indeed, the souring of political fortunes would render the radicals’ “act of refusal” an involuntary reality. Their anticonsumerism has an air of de haut en bas about it: Working people, stuck with stagnating wages for a generation, hardly have a choice in the matter. Likewise, the radicals’ incitation to simply drop out of the system, à la Timothy Leary, remains fatuous. Today’s “dropouts” are the hopeless, the unemployed and ever-neglected populations that find themselves on the wrong side of a border. Perhaps the most “utopian” dimension of Utopie Radicali, then, is the transformative possibility of politics itself, one that might finally right ancient wrongs.

You may also enjoy “The Designers Who Made Disco.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025