July 26, 2016

“Vertical Urban Factory” Traces the 250-Year Evolution of Manufacturing Spaces

A massive new volume makes the case for manufacturing to return to cities, albeit in a vertical format.

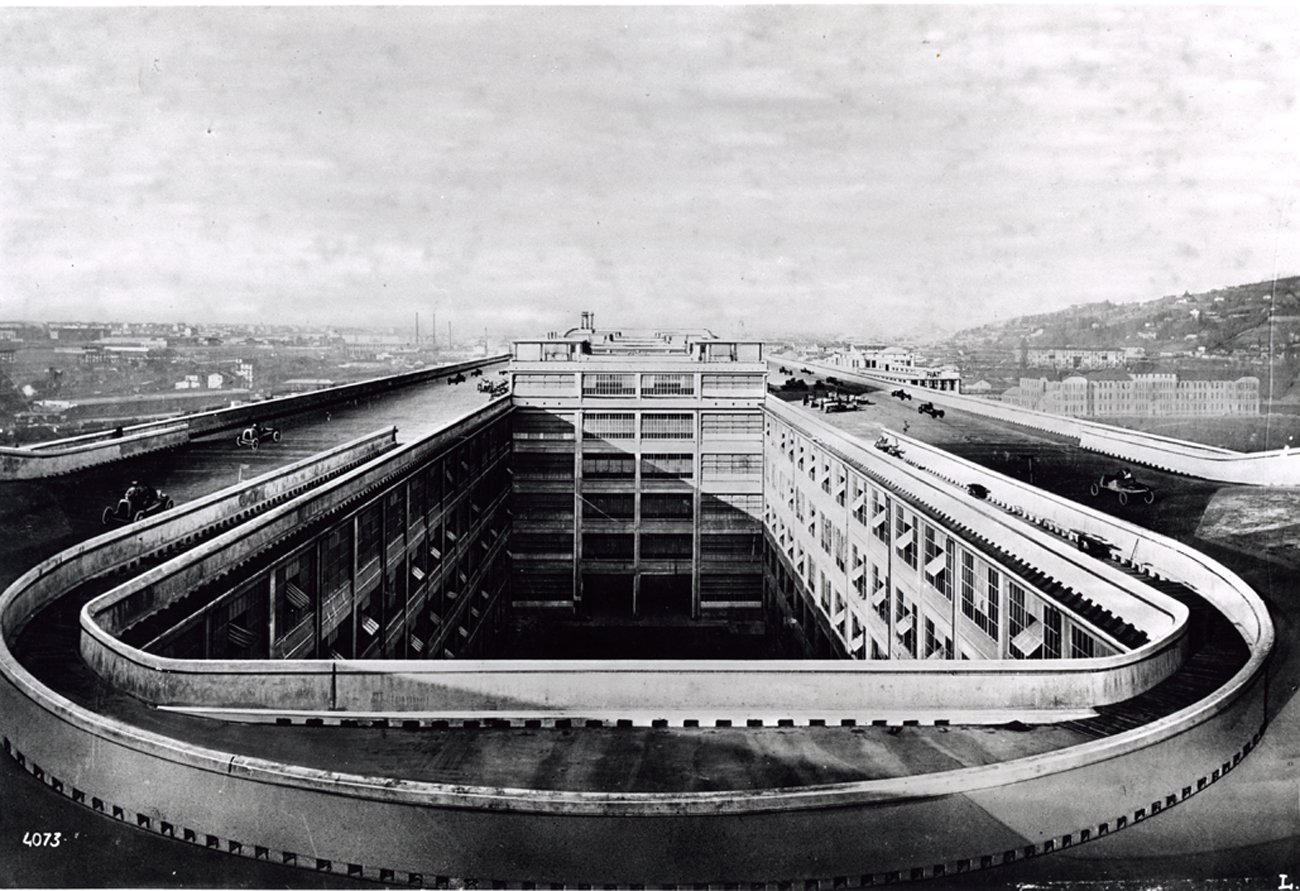

In Vertical Urban Factory, Nina Rappaport chronicles the history of a single building typology. Case studies punctuate the book’s 450-plus pages, such as the famous Fiat Lingotto factory in Turin and its glorious rooftop auto track.

Courtesy Archivio e Centro Storico Fiat

Nina Rappaport’s Vertical Urban Factory (Actar, 2016) is the fruit of nearly a decade of research, and at almost 500 pages, it shows. What began as a tangential line of inquiry became a jointly taught architectural studio, which then spawned a traveling exhibition accompanied by public forums, panel discussions, and a lecture tour. Essays and synopses appeared in 2012, incorporating the insights of the previous years. All this culminated in the new book, a comprehensive, lavishly illustrated survey of urban factory architecture from its inception around the middle of the 18th century down to the present. Not just a study of the factory’s architectural evolution, Vertical Urban Factory offers a trenchant analysis of the role it has played in shaping social space over time. Rappaport rightly argues that factories, though unjustly marginalized in the historical literature to this point, are key to unlocking the spatial logic of society today.

Beginning with the modern era, which she dates between roughly 1903 and 1945, Rappaport moves through to the contemporary period, inaugurated by the end of World War II and continuing to this day. In the book’s last chapter, she outlines the future of the factory in a manner less predictive than prescriptive. For Rappaport, the defining challenge posed by two centuries of industrialization and urbanization is how to promote equitable and sustainable growth within expanding cities. Her proposed solution is a “superurban symbiosis” that places tall, compact industrial zones alongside high-density residential blocks, thus bridging the gap between work and life.

The first of the book’s three sections sets the stage for the modern factory by describing the epochal shift from feudalism to capitalism. From there, it proceeds through the First (1760–1830) and Second (1870–1914) Industrial Revolutions. Inventions like the power loom and the cotton gin were characteristic of the First, gathered under one roof in workshops, manufactories, and mills. Conveyor belts and rivetless overhead runners were signal innovations of the Second, used in the assembly line at Henry Ford’s Highland Park, Michigan, auto plant. Rappaport relies on Karl Marx’s critique of political economy and Henri Lefebvre’s work on the social production of space in explaining the dynamics of capitalist production. Michel Foucault’s concepts of heterotopia and the panopticon recur throughout, as she contends that factories have combined elements of both. Her discussion of factory towns invokes Margaret Crawford’s notion of “pragmatic utopias”—i.e., attempts to realize ideal communities within the bounds of existing society. On factory architecture and machine-age design, the text refers to writings by the historian Leonardo Benevolo as well as the critic Reyner Banham. Brinkman and Van der Vlugt’s Van Nelle complex in Rotterdam is a paradigmatic instance of the modern factory for Rappaport: a multistoried block sheathed in glass, equipped with hanging conveyors, raised gangways, and elevated chutes.

The Third Industrial Revolution (1971–present) takes center stage in the second section, which deals with the contemporary factory. Commonly characterized as “postindustrial,” this economic phase is chiefly driven by informatics and robotics rather than manufacturing and hand-operated machinery. Whereas modern factories were associated with production, their contemporary counterparts are associated with consumption. Consequently, factory jobs tend to be replaced by those in the service sector, with heavy industry pushed out of city centers by light industry. Here, Rappaport follows the lead of Marxist intellectuals such as Ernest Mandel and David Harvey in interpreting the post-Fordist, neoliberal era as one of “flexible accumulation.” Capital is less rigidly attached to particular sites, as global competition pulls ever more distant lands into the market’s orbit. Meanwhile, the commodities produced by this economy are increasingly intangible, with digital networks of communication, microchips, and satellite feeds usurping the comparatively clunky, bulkier productions of old.

Volkswagen’s massive Gläserne Manufaktur (Transparent Factory) in Dresden invites onlookers to watch the production process.

©Volkswagen AG

Borrowing a phrase from the autonomist Antonio Negri, Rappaport conceptualizes the work involved in this type of production as “immaterial labor.” Contemporary factory architecture largely mirrors this newfound flexibility and dematerialization, emphasizing adaptability, fungibility, and mobility on the one hand and transparent, spectacular surfaces on the other. Workplaces can be set up or torn down at a moment’s notice in vacant warehouses or loft apartments. Jeppe Street in Johannesburg is one such case of adaptive urban reuse, while Volkswagen’s massive Gläserne Manufaktur (Transparent Factory) in Dresden, a marvel of pellucid construction, transforms manufacturing into public spectacle, with onlookers invited to peer inside. The “consumption of production,” Rappaport smartly observes.

Admittedly, this is a huge amount of data to contextualize, particularly given the book’s rather narrow focus on a single building type. It would be far too much for Rappaport to investigate from scratch. Luckily, as she points out early on, a great deal has already been written on the periods from the vantage of sociology, urban studies, and architectural history. Vertical Urban Factory nevertheless retains a continuity and integrity all its own. Rappaport weaves in insights and observations from a wide range of theorists without coming across as academic, and balances them out by drawing original inferences. This by itself is an impressive feat, requiring no small degree of skill. Graphic designer Sarah Gephart’s chronological overview, which spans more than 20 pages, also helps, presenting a timeline tagged with multiple markers that identify concurrent developments in culture, technology, workplace management, and industrial design. It’s a point of reference to which readers can return, as Rappaport unfolds her narrative in a somewhat nonlinear fashion. Now and then the prose, too, can be a little dry, but this has more to do with the topic at hand than with the author’s style. For the most part, Rappaport manages to keep things lively and engaging, to say nothing of her mastery of the material, which practically spills off each page.

Besides, Vertical Urban Factory introduces several useful new concepts. One of these, “process removal,” designates a technical procedure by which “all evidence of how and where something is made” is erased. Using a slightly different vocabulary, this could be seen as a mediation of the production process, itself a form of mediation. A false immediacy is thereby conferred on all manner of products, which appear magically shrink-wrapped, parceled out, and ready-made.

This gets at Rappaport’s broader distinction between economies of production and economies of consumption. In the former, factories are geared to produce as much as possible. In the latter, they are specifically tailored to meet consumer demand, customizable with just-in-time production. Consumerism is a somewhat misleading concept, however, and viewing consumption as the determining economic factor of postindustrial society is not entirely accurate. Production still determines the metabolic interaction of humanity with nature, as well as its social organization. What has perhaps changed between the two periods is not so much the objective structure of being as the subjective structure of consciousness. Rappaport hints at this when she speaks of workers’ consciousness: Whereas before they recognized themselves in what they produced, today they recognize themselves in what they consume. She might have put a finer point on it.

Likewise, “immaterial labor” fails to capture the specific features of the contemporary moment. Negri has much to answer for in popularizing this category, as the phenomenon was better grasped as mental labor (traditionally opposed to manual labor). Furthermore, it is unclear to whom the book’s final section concerning the future is addressed. Will the measures suggested by Rappaport—the imperative, among others, to “redress labor conditions for a democratic workplace”— be taken up by private citizens or by public officials? A social agent is required, one that does not yet exist.

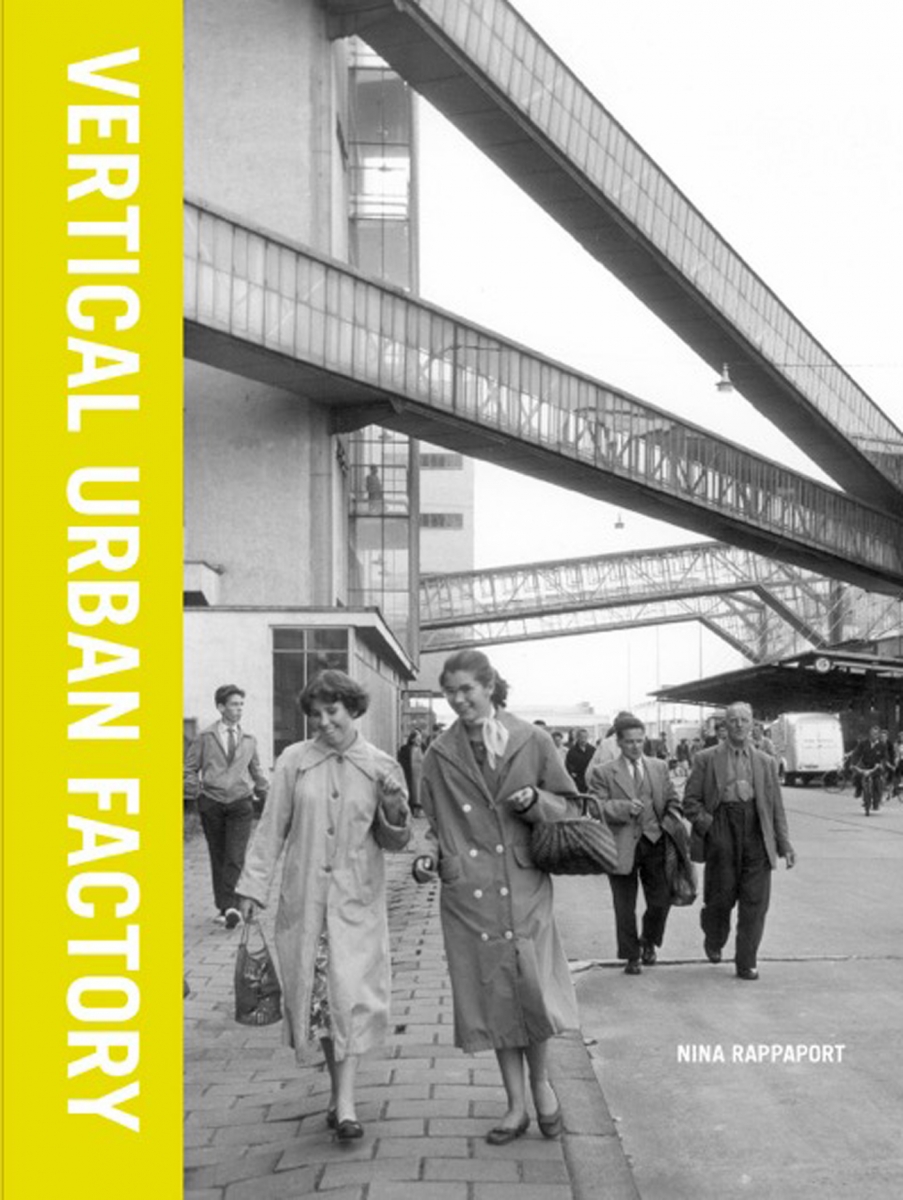

Brinkman and Van der Vlugt’s Van Nelle complex in Rotterdam is for Rappaport the paradigmatic example of the modern urban factory.

Courtesy Actar

A female worker at the Van Nelle factory scans a conveyor belt for defects.

Courtesy Collectie Gemeentearchief Rotterdam

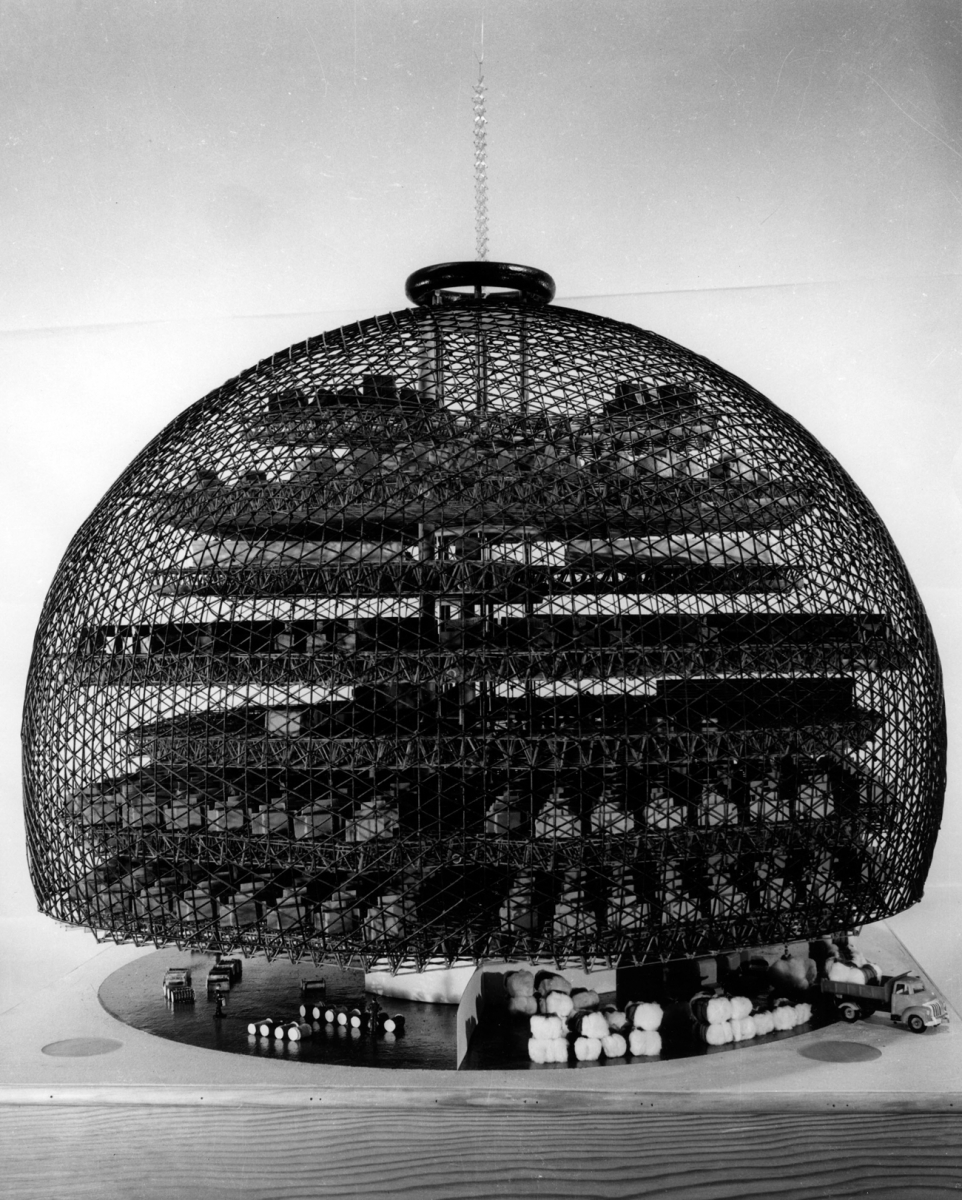

Buckminster Fuller’s speculative 1952 proposal for a cotton mill was astonishing for its innovative integration of mechanical services.

Courtesy North Carolina State University, College of Design/Photograph by Ralph Mills

Rappaport tracks how architectural style has accompanied the shift away from heavy industry to our present “postindustrial” era. Above: The Noerd Building (2011) near Zurich

Courtesy Gaston Wic

An employee at the Shinola factory in Detroit

Courtesy Nina Rappaport

Designed by Abalos & Herraros Architects, the waste management plant in Madrid recycles urban refuse.

Courtesy ©Luis Asin, 1999

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025