December 3, 2021

Can Designers Help End the Waste Age?

It remains to be seen whether we’ll be collectively willing to make the lifestyle sacrifices that are needed to end the waste age, or whether the planet becomes yet another thing we decide to throw away.

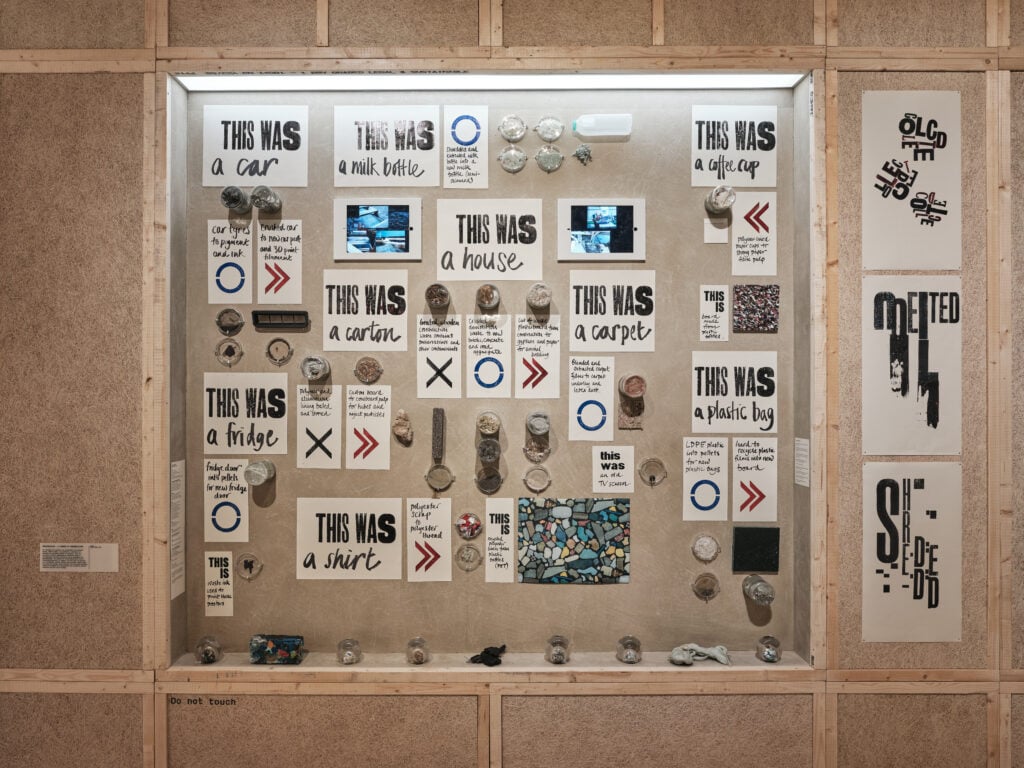

To see the problem so starkly laid out is uncomfortable, to say the least. An installation of 6,600 bottle tops collected over a single winter in Cornwall covers half a wall, while Edward Burtynsky’s photographs of mines and landfill sites serve as a reminder of the irreversible damage we have done to the earth. It is further illustrated by exhibits such as Italian design studio Formafantasma’s Ore Streams project, on electronic waste and how to curb it, and Dutch practice Studio Drift’s Materialism, which catalogs the materials that make up everyday objects—such as cars and phones—and presents them as a series of relatively-sized blocks.

Primed with all this information, the exhibition gives hope that things can change. With examples of how waste can be embraced or reimagined, visitors are shown everything from fashion made from offcuts to chairs 3D printed out of recycled plastic, to kintsugi-esque efforts to make a virtue of damage and repair, to biomaterials created out of discarded organic matter. Other displays illustrate how to stop creating waste in the first place—rentable lightbulbs, a toaster that never breaks, and easy to disassemble furniture that can be upgraded. It’s an optimistic and heartening vision of the future—not one of hardship and scarcity in face of our future challenges but one in which we live more communally and compassionately, with greater respect for our resources and surroundings.

What is largely missing in this show, though, is an analysis of how these solutions will be implemented and the underlying political context they need to respond to—the answer simply cannot just be to make more stuff. The opaquely presented statistic that low-income people account for only five percent of the waste generated (it’s not clear how this is defined or how it relates to population share) and an installation by artist Ibrahim Mahama made from e-waste dumped by Western countries in Ghana, is a reminder of the political nature of the waste age, and the economic structures that keep it going.

A more circular production system, the sharing economy, and the need to revisit pre-industrial practices are topics that are gaining increasing attention, but the disappointments of the recent COP26 conference made it clear that meaningful change requires enormous political will, ambitious investment, radical legislation, unprecedented co-operation, and the kind of long-term thinking that has so far been absent on the world stage. This may well not be the domain of the Design Museum, but it remains to be seen whether—beyond these creative innovations—we’ll be collectively willing to make the lifestyle sacrifices that are needed to end the waste age, or whether the planet becomes yet another thing we decide to throw away.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

Rice University’s New Architecture Hall Revives Terra-Cotta Tradition

Swiss firm Karamuk Kuo’s first U.S. project merges craft and performance with a custom ceramic rainscreen facade.

Viewpoints

Is the Furniture Industry Failing to Connect the Dots?

Mebl’s Michael J. Hirschhorn and Lot21’s Lew Epstein explore how the industry fails to understand how broader social, environmental, and health impacts are all interrelated.

Viewpoints

What ICFF Brand Directors are Most Excited About for 2025

Odile Hainaut and Claire Pijoulat give METROPOLIS a preview of this year’s theme, floor plan, and sustainable design highlights.