May 22, 2020

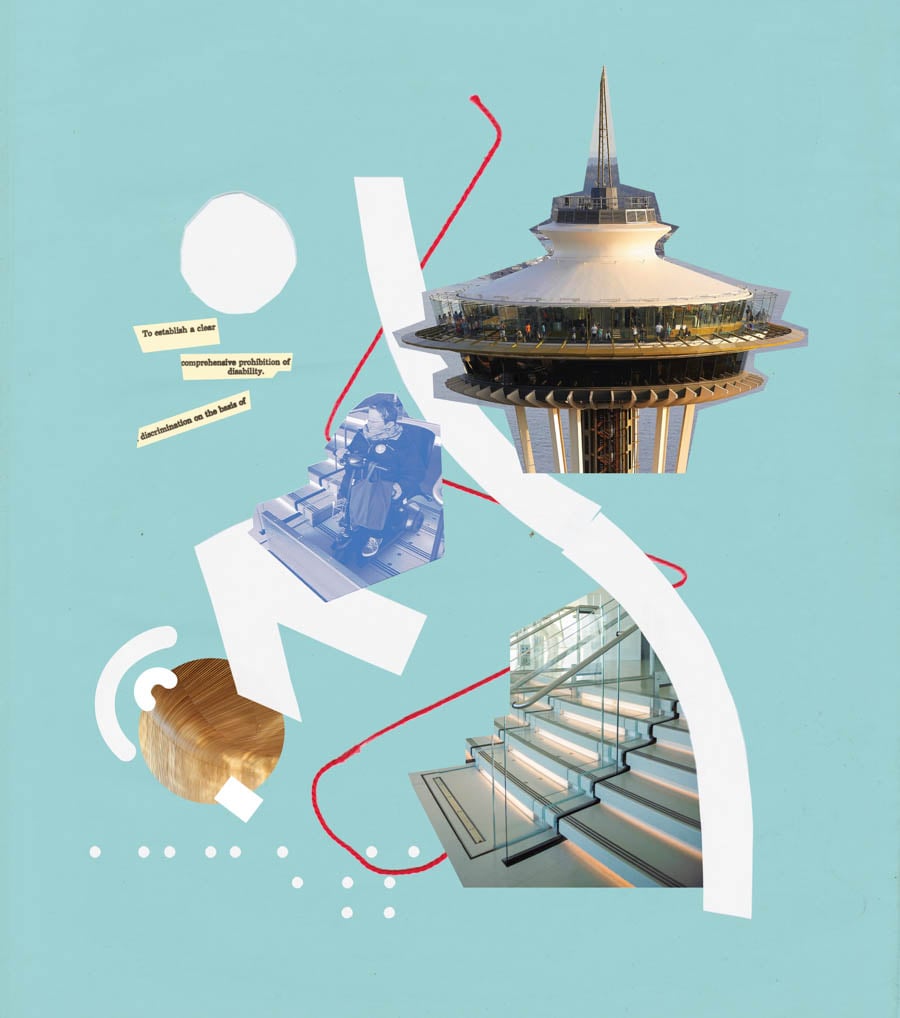

Why Are There So Few Great Accessible Buildings?

Design historian Bess Williamson assesses the state of accessible architecture in 2020, which marks the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Barely two weeks after the New York Times praised Steven Holl Architects’ new $40 million Queens Public Library branch in Hunters Point as “one of the finest public buildings New York has produced this century,” several local blogs revealed its missteps when it comes to accessibility. The fiction section, for instance, features a lofty hideaway of shelves framed by steps on either side, creating cozy reading nooks but eliminating access to the shelves for wheelchair users. In fact, the building overall seems to be designed for only stair-walking types. Among a range of staircases, floating platforms, and stepped seating arrays, it is equipped with only one elevator, which might set off alarm bells for anyone who has ever attended a children’s storytime in a public library and tried to navigate the space with a stroller.

Opened less than a year shy of the 30th anniversary of the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Hunters Point library stands as one of the more notable architectural blunders in several decades of them. The ADA was a landmark work of bipartisan civil rights legislation and the first countrywide law in the world to require access across public and private spheres. Its emphasis on the built environment as a barrier to inclusion is the model for other countries’ guidelines and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. And yet when we hear the term “ADA compliant,” we hardly think of great architecture. Few architects have adopted the notion of access as a form giving principle: Instead, the work of access remains a legal minimum, and its design features are often left to lower-level design staff and rarely noticed unless they are not working. Indeed, as the New York Times noted in a follow-up article, Holl’s design was in compliance with the law, given that the library offers a retrieval service for any patron who is not able to visit the stacks. For the kinds of buildings most likely to be viewed as icons of contemporary design, access is rarely more than an afterthought

As a professor of design history, I often ask students to name notable examples of accessible architecture: What icons can we point to as great illustrations of integrating the rules they’ve learned about ramp grade, bathroom layout, or sound quality in buildings? They rarely have reference points, though some may name Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum as a possibility. (Although Wright himself did not express interest in accessibility, many wheelchair users identify the ramp as a joyful, if steep, experience.)

To find the best examples of accessible architecture, we need to seek out disabled people themselves—as architects, project planners, and occupants of buildings. Today, some of the best examples of accessible architecture—buildings that truly stand out for their accomplishment of accessibility far beyond the legally required basics—reflect a more positive outcome of the post-ADA era: greater agency and representation of disabled people. In the past two decades, as disability community organizations have expanded to serve a population with more rights, some of them have been able to put capital and creativity toward new buildings that model approaches to design that exceed legal requirements.

In 2007, Access Living, a community-based organization founded by and for disabled Chicagoans, opened a new headquarters designed by LCM Architects, a firm whose principals include Jack Catlin, a disabled architect who had worked with the organization for several decades as an advocate for improved access in the city. The building, a four-story office block on a busy section of West Chicago Avenue between two subway stations, has a welcoming, open entrance at grade rather than separate wheelchair and stepped entrances. Its interior floors are organized around two large elevators, which also create the visual profile for the building as a vertical brick block with a glass facade. In the office areas, adjustable-height desk systems, soft upward lights, and spacious doorless bathrooms all represent accessibility built-in from the start. Overall, Access Living has the appearance of a professional office space (which it is), but its design aesthetic of open and airy, geometric space offers a high-design look that was rarely associated with community-based organizations in prior decades.

In the 2010s, two important nonprofits in the Bay Area—Berkeley’s Center for Independent Living (TheCIL) and San Francisco’s LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired—moved into new office spaces that offered distinctive design.

TheCIL was founded in the 1970s as a grassroots organization seeking independence for its members, and over the years had been the origin point for several offshoot groups, including the Bay Area Outreach and Recreation Program, Through the Looking Glass (an early childhood and family education center for families with disabilities), and the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund, one of the leading legal advocacy groups of the U.S. disability rights movement. While these groups tended to be located in renovated and improvised spaces during their growth, the project to build a shared campus signaled the greater symbiosis of their network. The Ed Roberts Campus, designed by Leddy Maytum Stacy Architects, opened in 2011 as an 80,000-square-foot, two-story building that includes entrances from a parking lot, rapid-transit station, and sidewalk, all connected with a spacious elevator with large buttons at foot level that can be bumped easily by wheelchairs, feet, or children’s hands. In the entrance, and visible from outside, is a large red ramp that provides ample room for two wheelchairs to pass each other as they roll up and down to and from the second floor. This ramp provides a visual cue to the building’s accessibility, but many other features make access both visible and seamless, from advanced air-filtration systems to accommodate people with chemical sensitivity to a water feature that allows blind visitors to orient themselves by sound. Like Access Living, the Ed Roberts Campus was designed with an explicit focus on being a model of universal design as well as a functioning building for disabled and nondisabled workers and visitors.

With the support of a major fundraising campaign, San Francisco’s LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired was similarly able to pursue a headquarters that empowered its users, moving into a renovated office building in the Civic Center area in 2016. The building takes a different approach from the cross-disability organizations at Access Living and the Ed Roberts Campus by designing primarily with blind and low-vision people in mind. That means features like textured floors, tactile handrails, and a strong emphasis on quality of light, providing wayfinding tools for those who use white canes or touch to navigate, or who are sensitive to harsh lighting. The principal designer, Mark Cavagnero, collaborated with Chris Downey, a blind architect and the president of the LightHouse, to attend to the usability of the building. A prominent skylight and adjustable lighted wall panels show the architects’ awareness of the spectrum of vision in the blind community, rather than the widespread perception of blindness as a total lack of sight. Acoustic quality, too, is significant— from the sound of steps on the Brazilian hardwood stairs to finely tuned, accessible sound systems.

In all of these buildings, design signals the solidity of these organizations and networks to a 21st-century disability community. They also track changes in architectural practice since the ADA, particularly as the architects closely engage disabled people in their design processes. Disabled architects Catlin, Downey, and Karen L. Braitmayer of Studio Pacifica contribute first-person experience to the technical definitions of access represented in codes.

Access Living, the Ed Roberts Campus, and the LightHouse remain less familiar to many students and designers than higher-profile libraries and museums, but perhaps they will shape new practices that center disability rather than treat it as a sideline. Their form-focused approach to accessibility reflects the growing prominence of disabled people in public life, and set a higher standard than “ADA compliant” for buildings to come. Further, all of the buildings exhibit a certain flexibility— anticipating a range of users’ abilities, as well as giving extra space or multiple means of interacting or moving through the space. In pandemic times, designers are newly aware of uncertainty and the need to prepare for sudden changes of plans. These disability-specific spaces, reflecting the design work and knowledge of disabled people themselves, show that access can be a creative pursuit far beyond the legal minimum.

You may also enjoy “Mabel O. Wilson is Updating the Narrative of American Architecture to Include Black Architects”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.