September 15, 2017

New Exhibition Showcases Stunning Pieces by the Wiener Werkstätte

The Neue Galerie’s “Wiener Werkstätte 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty” opens October 26.

When Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Fritz Waerndorfer established the Wiener Werkstätte in May 1903, bringing together artists, designers, and craftspeople under one roof, it is unlikely that they comprehended the prescience of their approach to design and fabrication. Unsatisfied with outside manufacturing firms, the young Viennese designers took inspiration from the British Arts and Crafts movement and sought to counter what they saw as the impersonal character and low quality of goods made by more industrial means.

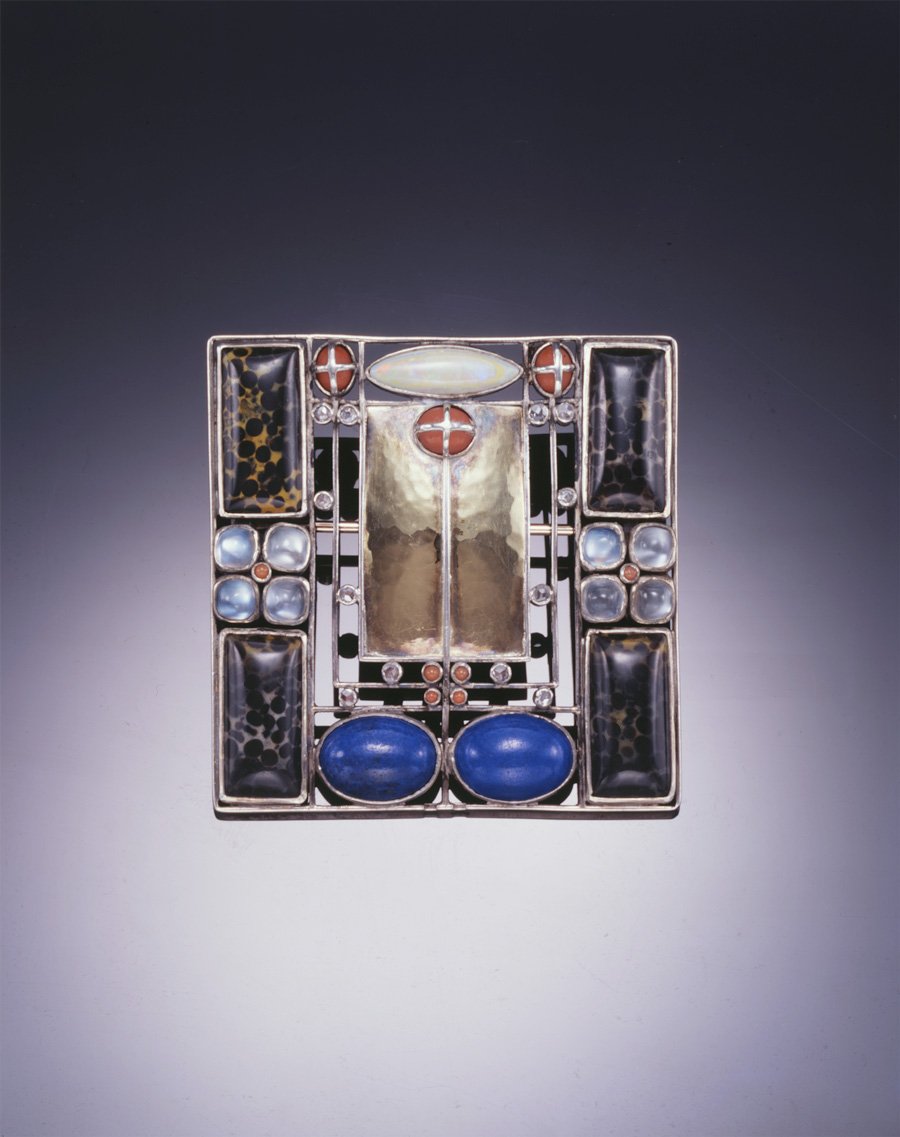

“They tried to move away from an industrialization method of production,” says Janis Staggs, cocurator of an upcoming comprehensive exhibition at the Neue Galerie that examines all aspects and artists of the Wiener Werkstätte style. The exhibition, titled Wiener Werkstätte 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty and opening October 26, focuses on how the young designers, artists, and patrons associated with the style were motivated by a renewed focus on quality, and how products can serve to elevate the lives of their users. Its galleries will reflect the prolific output of the group in Europe and the United States, encompassing such diverse media and products as furniture, drawings, fashion, architecture and interior design, wallpaper, and decorative objects. Exemplary pieces include a 1904 brooch of diamond, opal, and other precious stones by Hoffmann and a 1920 bird-shaped silver candy box by Dagobert Peche, a creative director of the Werkstätte from 1917 to 1919.

Despite its lofty ideals, however, the collective’s functioning was very much conditioned by the economic and political turmoil that defined Europe in the early 20th century. With the outbreak of World War I, for example, many of the Werkstätte’s craftsmen were conscripted for military service, and access to metals required for production was restricted by the state. And, lacking an effective business strategy or management structure, the firm was especially vulnerable to the global economic fallout following the 1929 stock market crash. “They knew a lot about art, but they knew nothing about business,” says Staggs. Furthermore, cultural trends shifted away from the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art,” approach so valued by the Werkstätte: “People didn’t want to live in a space completely designed in one aesthetic,” Staggs explains.

Even with the collective’s relatively short life span, characterized by a tension between the luxury aesthetic of its output and the persistent indigence of its artists, the Werkstätte’s approach to production can be understood as laying the groundwork for contemporary design and, more generally, consumer culture. Its emphasis on quality materials, consumer knowledge, small-scale fabrication, vertical integration, and custom production foreshadowed central aspects of contemporary material culture. As the exhibition makes progressively clear, the Wiener Werkstätte’s design thinking, creative output, and work culture continue to affect—and mirror—the design experience.

You may also enjoy “Rediscovering Sottsass: A Q&A With Met Curator Christian Larsen.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025