April 20, 2018

Architects, Armed with Data, Are Seeing the Workplace Like Never Before

Today’s designers are taking an increasingly sophisticated approach to workplace design, using sensors, internet-connected furniture and fixtures, and data analytics to study offices in real time.

This article is part of the “tech x interiors” special section that was guest-edited by the design firm Studio O+A. The section, which appeared in the April 2018 issue of Metropolis Magazine, explores how technology is reshaping the workplace. You can find the full section online here.

A workplace that improves employee productivity and efficiency has been a white whale of corporate managers for decades. But even before the office as we know it today was born, designers and innovators were already studying sites of labor, such as the factory, to devise strategies to boost worker performance. By the 1960s, Robert Propst, the inventor behind Herman Miller’s Action Office line of workplace furniture, and others were conducting workspace research that would ultimately lead to the creation of the modern cubicle.

These developments relied largely on observation and intuition to organize office workers in purportedly effective ways. Now, advances in technology allow designers to take a more sophisticated approach, using sensors, internet-connected furniture and fixtures, and data analytics to study offices in real time. “You can take into account every single employee, and people are very different,” says London architect Uli Blum. “It’s about solving the fundamental problems of getting people the environment they need. And the easiest way is to ask them,” he adds. But finding out the needs of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of workers can quickly become an exercise in futility.

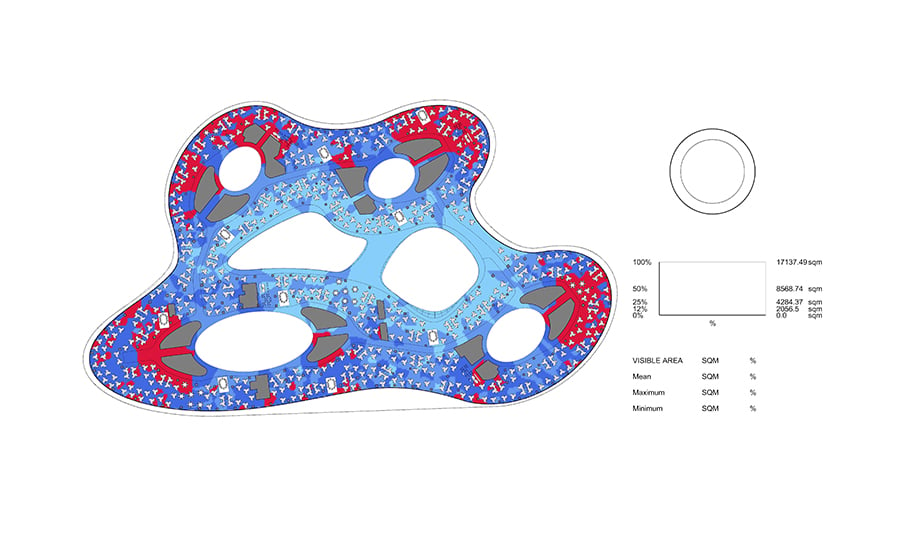

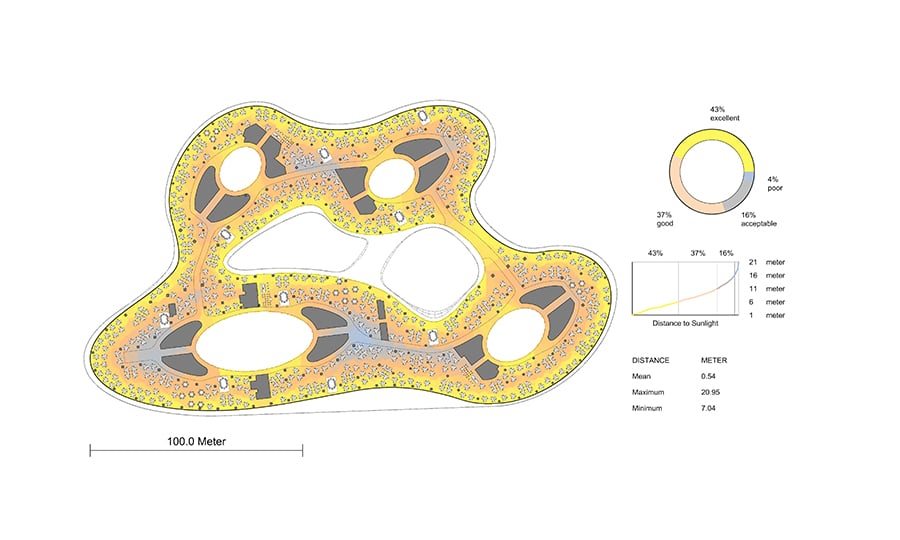

Blum helped found the Analytics and Insight unit at Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) three years ago. His team has focused its early efforts on devising methods to study the workplace and anticipate employee needs. Naturally, Blum decided to experiment with his own office first: “We installed sensors to understand our own workplace better,” he explains, referring to a cluster of devices that monitor visibility, noise, humidity, light, temperature, and air quality. Among these were smart surveillance cameras that track the location, but not the identity, of workers over time. “They don’t know who they see,” Blum says reassuringly.

The ongoing experiment gauges how employees navigate their workplace to find the spaces that work best for them. It has also become a tool for justifying the firm’s signature aesthetic. “A lot of our designers produce beautiful shapes,” he says. “But we need to be able to prove why those shapes are better than others. So we look at ways to compare, and that involves looking at spatial data.”

An effective workplace design, Blum suggests, is not one that optimizes all areas to the same standard, but one that accommodates the whole range of space and personal preferences. Yet in this way, he shares a fundamental assumption with the designers of the past: A space either helps or hinders the organization that uses it, and the designer’s challenge lies in finding out exactly which differences in a workspace will make a difference for the organization.

Frederick Winslow Taylor is widely known for shaping conditions of industrial labor in the early 20th century, but his work also had a significant impact on the development of the modern office. Scientific management, the field Taylor pioneered, improved productivity on factory floors by streamlining industrial processes according to insights gleaned from observation. By understanding the machine, worker, and factory as integrally connected components of enterprise, disciples of Taylorism established the basic tenets of the modern workplace as the meeting of people, place and equipment. Contemporaries of Taylor, such as the husband-and-wife team Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, maximized worker productivity by reducing “waste time and motion”—as they called unnecessary movements in their many time-motion studies—from repetitive operations. Their techniques vastly improved output in an array of contexts like typing and brick-laying. But this approach had its limits: Workers can only move so fast, and they inevitably become fatigued.

One way past this hurdle was to shift the focus from workers to their environment, and to ask how space itself might alleviate stress and improve wellbeing. The installation of air conditioning in factories at the turn of the century was motivated by the promise of increased machine efficiency, but it was also, incidentally, an early instance of workplace design for wellness. The idea worked, and it was a similar logic that saw AC become commonplace in the modern office, where early studies claimed gains in typist productivity of nearly a quarter.

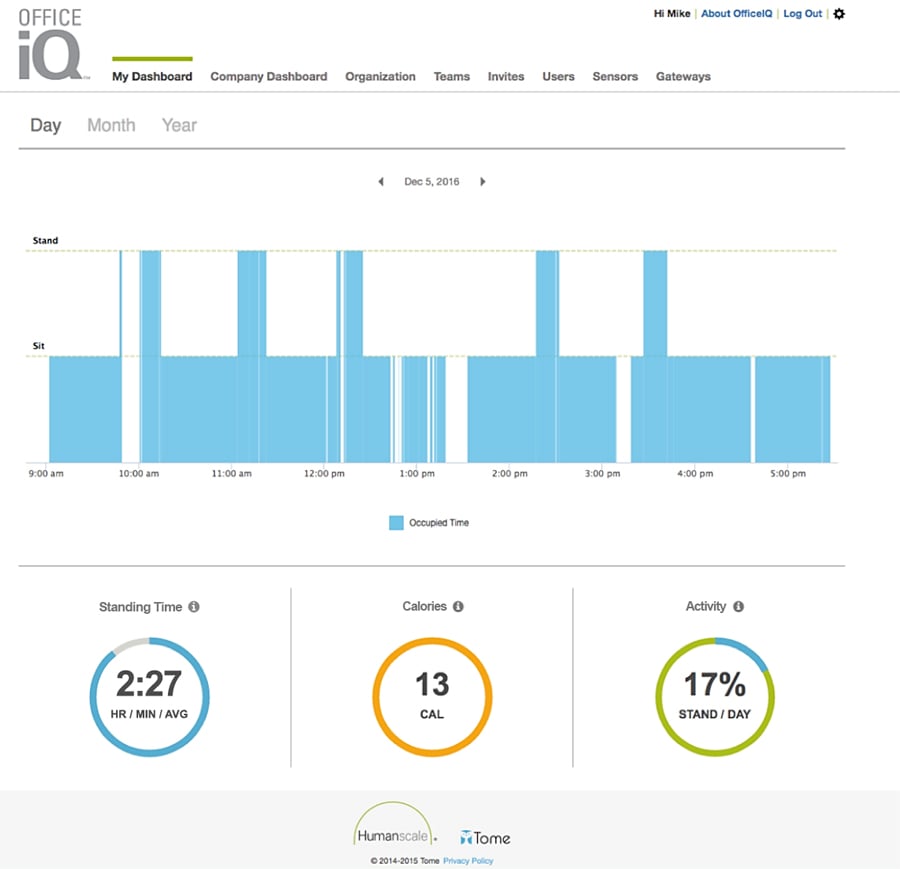

Today’s workplace experts like Blum are similarly concentrating on the relationship between work environments and employee efficiency. As the nature of work continues to evolve, finding the best ways to support workers remains a moving target. The furniture manufacturer Steelcase recently developed a digital and physical infrastructure that helps organizations use their space more effectively as more work takes place online. According to Scott Sadler, category product manager at Steelcase, “nearly half of all workspace is simply not being used.” The “Smart + Connected Workplace,” as the new concept is called, aims to streamline employee access to workspace and meeting rooms, and help organizations understand how their space is working. Connected sensors, signage, and furniture provide space availability data on a proprietary app down to the minute. Workers can seamlessly set up meetings by finding an available space that meets their needs through the app, then inviting attendees. The app will even reserve meeting rooms on both ends of a teleconference between employees working in different offices. “We try to bring all that data together so it can be where it’s most effective—in the palm of the employee’s hand,” Sadler says.

These new, immediate possibilities motivate workplace consultants like Arjun Kaicker, a collaborator of Blum’s at ZHA and the former head of workplace design at Foster + Partners. “In the past it was incredibly difficult to have a sophisticated approach to dealing with people individually,” he explains, and so more often than not planners spoke only to leadership. Even then, he adds, “if you had even 20 people, you had too many computational variables. Now we can do it instantly for 4,000 people.” Kaicker’s method suggests a turn toward mass customization in which workspace supply can be perfectly tuned to demand. “It lets us bring the user in,” he says. “Every workstation is different, so we can help people find the spaces that are best for them to work in. That’s never been done before.”

But not all architects are crunching numbers in search of an answer. For Jeffrey Inaba, a principal of the Brooklyn-based architecture firm Inaba Williams, the key to effective workplace design isn’t necessarily more information, but rather thinking strategically about what architecture can do for an organization as a whole. Spaces that can anticipate and respond to future changes in the business, such as rapid growth or downsizing, ensure that workplace architecture can effectively serve an organization in all scenarios. “The real architectural service is in thinking about how to question what the client needs,” Inaba says. “It’s the role of the architect to be projective about what can be introduced, rather than what is appropriate and obvious.”

Digital-first business models are loading other demands onto the workplace, which is called upon to be an outward-facing, real-world representation of a company that customers have mostly encountered online. “The people who are coming to us realize that as the world becomes more virtual, and work becomes more immaterial, architecture becomes more important to their business,” he says. “It’s a way for them to stand out, to produce spaces that are special because they are physical.”

The definition of an effective workplace is, as ever, constantly changing. And for Inaba, every client’s needs are different. “In many cases the turn to the physical is one that they’re making for the first time,” he says. “Design is about revealing the questions that a company needs to ask itself.”

You may also enjoy “In 50 Years, The Workplace As We Know It Will Be Extinct.”