March 13, 2024

Billy Fleming and His Students Are Designing a Green New Deal

So, Fleming took the students to Narsaq, a small sheep farming town, which sits next to a largely untapped deposit of “green minerals.” For decades, this area supplied Europe and the United States with uranium to power homes and build nuclear weapons—meanwhile “spewing radioactive dust and tailings and all kinds of other things” around Narsaq, he explains. Now it’s in high demand as the world’s second densest deposit of rare earth elements such as neodymium which is needed for wind turbines and the motors in electric cars.

Here, Fleming’s landscape architecture and city planning students have the opportunity to imagine career paths outside of elite design firms, by learning from the frontlines of environmental crises and energy transitions. The studio’s main goal is to forge alliances with activists and the majority Innuit community, including from the movement Urani? Namiik! (Greenlandic for “Uranium? No!”), which fought to close the uranium mines, and Innovation South Greenland, a government agency that combines the roles of tourism board and conservation agency. Above all, the studio asks students to work in close collaboration with the communities they are designing for, to envision alternative futures.

This challenge begins with a hair-raising journey to Greenland’s tiny Narsarsuaq Airport (often listed among the world’s scariest landings.) This year, weather held up some students in Iceland.

Fleming’s studio introduces students to landscape architect Jane Hutton’s theories of reciprocal landscapes and considers how the “far-away, invisible landscapes where materials come from” are linked to cities where most consumers—and designers—live. Narsaq was chosen as one such place, against competition from the lithium rich salt flats of Atacama Desert and Cobalt-mining regions of the Democratic Republic of Congo. “Places like South Greenland are only on the radar of climate scientists and mining operators, and, obviously, the people who are from there. Those are places where the work you do in a studio—and the work you do after a studio, the work you do in academic and design research—can not just move the needle, but actually be part of much longer term, substantial and transformative.”

The Arkansas native’s criticism of design education is informed by his own zigzagging journey to pedagogy. Fleming, a landscape architect by training, worked in the Obama administration’s White House Domestic Policy Council’s Office of Urban Affairs and Economic Opportunity, before turning to organize opposition to Donald Trump as part of the Indivisible movement.

Today, he credits his time in politics to how he thinks about design and questioning: why do so many designers get the climate crisis so wrong? “The average design practice, however well-intentioned, is one of many contributors to biodiversity loss and climate change around the world,” he says. Fleming’s 2019 article in the journal Places made an example of Rebuild by Design, a design competition that invited firms to bid for funding for New York’s post-Hurricane Sandy recovery. The biggest awardee was The BIG U, a headline grabbing proposal for $335 million flood barrier system around lower Manhattan by architects Bjarke Ingels Group that included retractable floodwalls and waterfront parks. Rebuild by Design made admiring headlines with promises that designers could make climate resilience “playful”—before largely being shelved for a system of concrete seawalls. “It’s impossible to argue that the net impact of professional design practice has meaningfully reduced carbon emissions or addressed issues of spatial injustice,” says Fleming. “There are exemplary projects in each category, but they’re often a very small part of any firm or field’s broader practice or practices.”

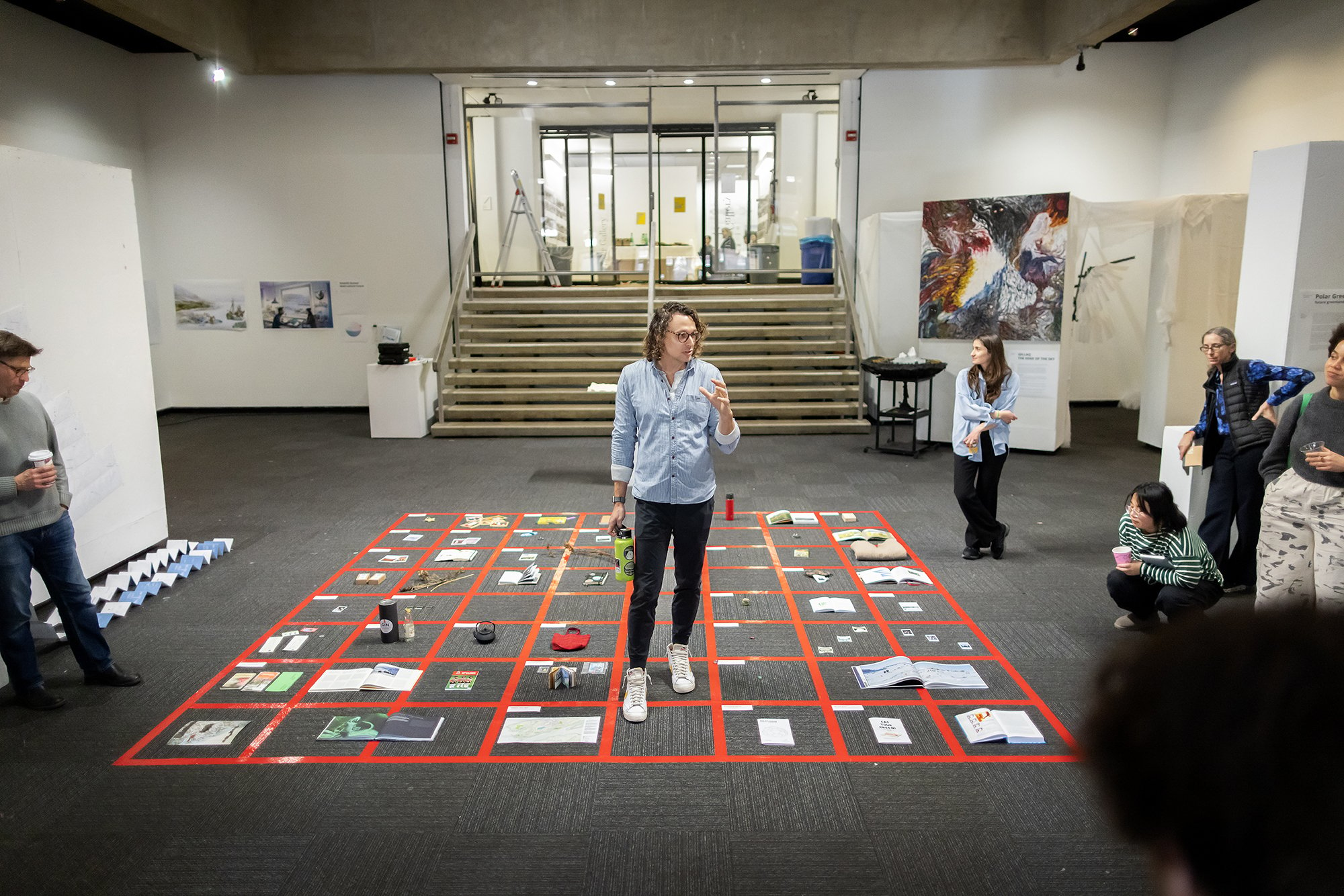

Five years on, he has put flesh on the bones of the policy proposal for the Green New Deal. The McHarg Center’s 1200 Project: An Atlas for the Green New Deal imagines that the nation will be ready at some point for “massive, national-scale action on climate” and tries to populate the missing spatial design solutions that it would need.

He wants students to be a part of this process, in envisioning, “high-impact built projects and prototypes for the resilient futures we’ve been promised.”

He remains unconvinced that the travel studio—with its emphasis on fleet-footed global adventures—can ever make sense in today’s climate. But if this journey can make Narsaq more visible to the world outside, perhaps it can also be redesigned as a prototype for building lasting collaborations. “It’s a place that matters deeply, not just to me, but to any question of a just transition or internationalism or climate justice. And it’s a place where I do feel like the work that’s possible within the constraints of an academic school of design can actually have an impact.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

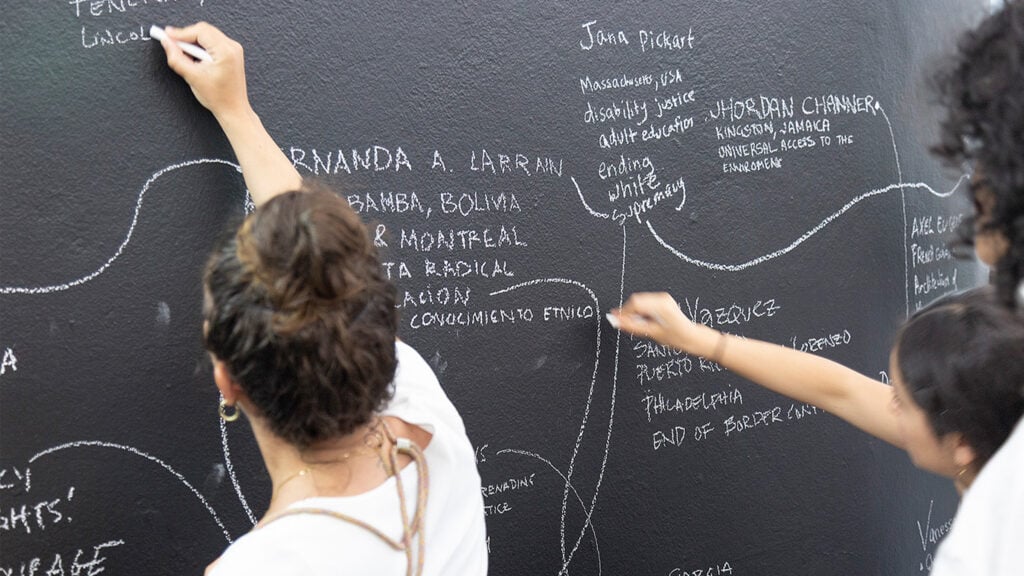

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.

Profiles

The Next Generation Is Designing With Nature in Mind

Three METROPOLIS Future100 creators are looking to the world around them for inspiration.