March 25, 2025

Ken De Cooman Is a New Kind of Architect

Through Nshimirimana, they built connections with local craftsmen, builders, and the wider community. Most importantly, they listened deeply. “We learned from regional typologies, where industrial materials are not yet prevalent. Our perception of Burundi’s predominantly vernacular construction culture, combined with a low, self-funded budget, encouraged us to adopt and adapt local materials, spatial typologies, and bioclimatic principles.” Together with Nshimirimana and a team of 20 to 30 local workers, the young designers managed the project from fundraising to hands-on construction. For over two years, at least one of the four partners was always present on the construction site in Muyinga.

To manage the funds properly, they created BC Studies as a nonprofit legal entity. This later evolved under the BC umbrella to include BC Architects.

Collaborative Building in the European Industry

They organized BC in a highly pragmatic way. To be able to “sign off” on building permits in Europe, they founded BC Architects as an architectural office parallel to BC Studies. As their projects grew, other architects and companies took an interest in their materials and products, leading them to establish their third branch: BC Materials, a production cooperative. This initiative primarily repurposed excavated earth from other construction sites.

“There was no set of finished plans to be checked by specialized engineers and handed to a contractor for execution, as we would do in Europe,” recalls De Cooman. “Instead, the design evolved with the construction, with everyone permanently involved in discussions. It was messy, it was intense, it was intuitive, it was imperfect—and that was not a problem.” They called this approach “architecture as prototyping” and had the sense that they were onto something, even if they didn’t yet know exactly what.

Subsequent projects for NGOs and foundations followed. They designed and built a community guesthouse and a hospital in Ethiopia for children with cancer, using adobe and local stones. Later, they completed three preschools in Moroccan villages in collaboration with the Good Planet Foundation. “For us,” says De Cooman, “a narrow definition of the professional architect no longer sufficed.” When the four partners gradually returned to Europe after years of working in Africa, they wanted to bring this direct and spontaneous way of building with them. But how could they translate these “acts of building” into Europe’s highly regulated construction industry? Their solution was to blend the collective, hands-on approach of African building traditions with the possibilities of European industry.

A Materials First Approach

They focused on natural materials such as earth, hemp, and vegetal fibers, developing a method based on workshops and constant prototyping. These materials are largely unpopular in the European design industry, but the architects found that engaging craftsmen and contractors early in the process made adoption easier. “We got deeply involved with every project, expanding our role beyond design. We became material consultants, organized workshops, produced our own materials through testing and prototyping, and trained contractors on how to use them,” says De Cooman.

In Belgium alone, about 40 million tons of earth are dumped or reused as landfill each year. BC taps into this waste stream, transforming it into beautiful, local, carbon-neutral, zero-waste products such as clay plaster, earth blocks, and prefab rammed earth. “It was never about maximum profit,” De Cooman adds. “We never hold back knowledge. Instead, we hope that many companies like ours emerge across Europe, rather than us becoming the biggest or most profitable.”

Sustainably Scaling this Practice

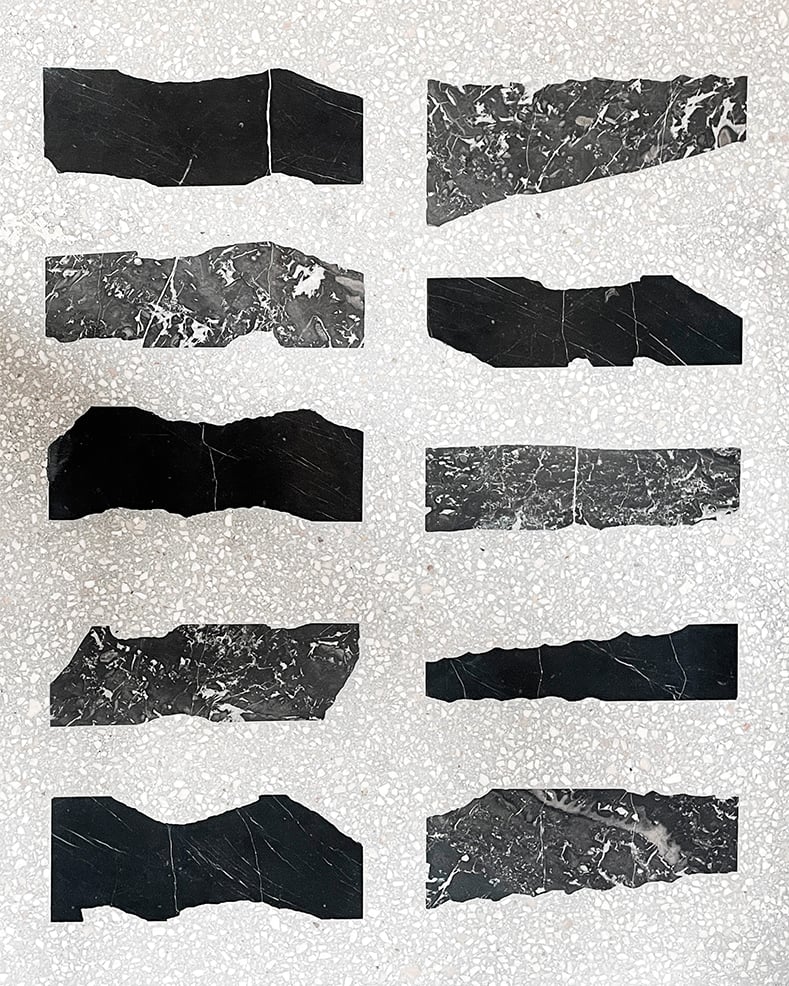

But is BC’s approach scalable to larger projects? “We are currently finding that out,” says De Cooman. BC recently completed its two largest projects to date: transforming a train depot in Arles, a city in southern France, into a design and research workshop for the Luma Foundation and converting former gendarmerie barracks in Brussels into a vibrant mixed-use quarter. These projects demonstrate how fully they have developed their methods. They start by scanning the surroundings for waste streams or sustainable materials, and adapting their designs accordingly. In Brussels, they primarily used salvaged bricks, hempcrete bricks, and clay plaster. In Arles, their most complex project yet, they incorporated waste from two nearby quarries and a recycling plant, as well as fibers and aggregates discarded by the local sunflower industry. After extensive testing and prototyping, they identified six waste products suitable for building: rammed earth, compressed earth blocks, earth mortar, acoustical earth plaster, algae plaster, and crushed roof tiles repurposed as terrazzo flooring.

The designers are already knee-deep in new projects, including the transformation of a 200,000-square-foot urban block in Brussels for a private developer. “Some real estate developers became interested when they saw we could handle larger-scale projects,” says De Cooman. For BC, this is another test of how far it can expand its methods. “We are very curious. If we want to maximize our impact on the building industry, this is the next logical step for us.”

Will BC change the industry, or will the industry change them? De Cooman smiles, “We will see.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

BLDUS Brings a ‘Farm-to-Shelter’ Approach to American Design

The Washington D.C.–based firm BLDUS is imagining a new American vernacular through natural materials and thoughtful placemaking.

Projects

MAD Architects’ FENIX is the World’s First Art Museum Dedicated to Migration

Located in Rotterdam, FENIX is also the Beijing-based firm’s first European museum project.