September 11, 2024

Shannon Goodman is Helping Make Material Reuse the Norm

Though the demolition contract had already been signed, Goodman—feeling a surge of courage and clarity after a six-month yoga teacher training—surprised herself by speaking up: Couldn’t some of the building’s original materials be salvaged for reuse, especially since Perkins&Will’s leadership was targeting LEED Platinum for the renovation? “Why would we only think about grinding this up and recycling? It didn’t make sense!” recalls Goodman. Working closely with the demolition contractor, Goodman went from assuming the endeavor would be a good exercise but not a “needle mover” to diverting 80 percent of demolition and construction waste (60 tons) from landfills and distributing it to more than 20 local nonprofit organizations.

“That was the beginning of everything,” says Goodman. Inspired and propelled by the office project, Goodman went on to cofound Atlanta’s Lifecycle Building Center (LBC) in 2011, with the help of private donors and supporters at the U.S. Green Building Council, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and other organizations that were equally compelled and captivated by Goodman’s passion. “If one commercial office building could have that impact, what could we do if we had that every day?” says Goodman.

The LBC has been answering that question for the past decade-plus from its headquarters in two 100-year-old warehouse buildings totaling 70,000 square feet on Atlanta’s industrial corridor Murphy Avenue. With a $70,000 operating budget, Goodman and her team of seven assess projects for deconstruction, help salvage and collect materials, store and redistribute those materials and products to nonprofits and disadvantaged communities, lead job trainings to create a workforce of people who are skilled in deconstruction and construction, and more. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Goodman also ran a $3.5 million capital campaign to renovate the warehouse. “It’s constant triage,” she says. “Though we’ve been around for 12 years, we are very tiny. Our industry is so grossly underinvested, and it will only change if there is an interest to expand to service the commercial sector.”

Despite its small size, the LBC’s challenges are emblematic of those embracing the growing deconstruction movement—or a circular economy—in the United States. The idea is simple enough on its face: To reach net zero by 2050 and avert the worst impacts of climate change—as called for in the Paris Agreement—building trades need to go beyond energy efficiency to address embodied carbon. Globally, cement and steel production alone account for 10 percent of CO2 emissions. In a 2022 report and circularity toolkit, Arup and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation put it this way: “In a circular economy, renewable materials are used where possible, energy is provided from renewable sources, natural systems are preserved and enhanced, and waste and negative impacts are designed out. Materials, products, and components are instead managed in loops, maintaining them at their highest-possible intrinsic value.”

But the stumbling blocks are many: There is no clear road map or framework for stakeholders, policymakers, and others for developing, financing, or operating these “managed loops.” In some cases, cities are taking the lead. Ithaca, New York; Portland, Oregon; Baltimore; Palo Alto, California; and San Antonio have all adopted deconstruction ordinances. And some, like San Antonio, have material collection programs similar to the LBC’s, as well as contractor training.

But Atlanta, said Goodman, is not going to lead from the top down. “It will have to be incentivized,” she says. Because of that Goodman helped develop ReBuildATL, a coalition of more than 40 local nonprofits, academic institutions, industry partners, and government agencies dedicated to community and industry outreach and education, as well as paid vocational training for disadvantaged individuals, enabling them to find long-term, living-wage jobs in construction, demolition, remodeling, facility management, and more. “The long-term moonshot for this whole initiative is to enable low-income homeowners and residents to address deficiencies and issues in their homes, like a hole in the roof or an inefficient building envelope,” says Goodman. “They most critically need access to renewable, lower-cost energy, and are the least positioned to access it.”

Another area where Goodman hopes to see progress is in what those in the industry call “material passporting”—the standardized system through which suppliers, contractors, and architects can more easily log and specify reclaimed materials from deconstructed buildings. Europe has gone much further in this area: Madaster is used by at least six European nations as an online registry of materials and products from the built environment, with insight into how they could be used again. In the United States, Goodman says, companies like asset management and exchange platform Rheaply are aiming to do something similar.

To that end, Goodman is expecting to hear this summer whether Build Reuse—a nonprofit empowering communities to reuse construction and demolition waste, where Goodman is on the board—will receive a $6.7 million grant to help develop Environmental Product Declarations (or EPDs) for reclaimed materials. EPDs tell specifiers about the environmental impact or performance of a material over its lifetime, allowing them to choose the most sustainable option. “Reclaimed building materials have really low embodied carbon, but how can you quantify that?” asks Goodman. “Build Reuse will lead this process to create this EPD system for a dozen or so categories to begin to give reused materials a seat at the table.”

Finally, Goodman wants to be telling more stories about reclaimed materials and where they end up, or the jobs created in the process (such as the five formerly incarcerated people whom the LBC was able to hire full time, with benefits, to help clean up the warehouse’s site, a former brownfield). The more people can see that through line, the more inspired they will be to adopt and engage in deconstruction. There’s also a “yuck factor perception”—the moment that something is treated as trash, it loses value. “Our systems aren’t designed for that value to be utilized,” says Goodman. “Nothing is going to change systemically if we’re focusing on making people feel bad. We have to give them a reason to do something different. They have to see those stories of impact.”

THE FUTURE OF COMMERCIAL MATERIAL REUSE

In November 2023, Mannington Commercial announced its Build Reuse membership, making it the first flooring manufacturer to join the national organization, for which Shannon Goodman serves on the board. The nonprofit is dedicated to the recovery and reuse of building materials, and Mannington joins a growing membership network that includes Rheaply, Urban Machine, and Elkus Manfredi Architects (p. 62), among other groups from real estate developers to construction companies, reuse retailers, deconstruction contractors, and salvage companies.

Through the partnership, Mannington’s associates working with customers on projects can now contact Build Reuse when projects require the removal of carpet products. Build Reuse then collaborates with its local market partners to determine the most environmentally responsible removal method and identify reuse outlets for the recovered carpet.

According to Goodman, Build Reuse is currently focused on facilitating the expanded reuse of carpet tile, but the model will be adaptable for other product types, such as LVT, in the future. “Through this collaboration, we are demonstrating how a product manufacturer can proactively change not only their own behaviors to expand reuse practices but also create behavioral shifts in the marketplace by inspiring other manufacturers, clients, specifiers, and others in the built environment ecosystem to choose material recovery and reuse as an alternative to disposal,” says Goodman.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

- No tags selected

Latest

Products

Discover the Winners of the METROPOLISLikes 2025 Awards

This year’s product releases at NeoCon and Design Days signal a transformation in interior design.

Profiles

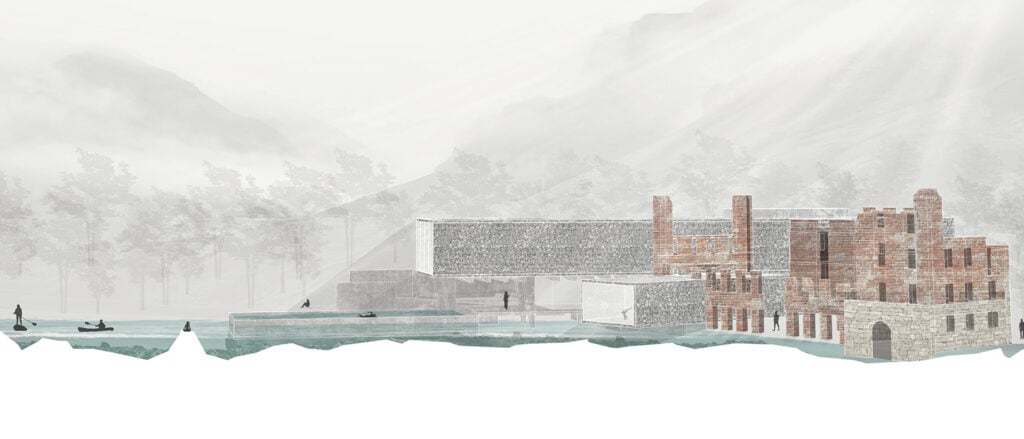

These Architecture Students Explore the Healing Power of Water

Design projects centered on water promote wellness, celebrate infrastructure, and reconnect communities with their environment.

Projects

KPF Reimagines the Arch in a Quietly Bold New York Facade

The repetition of deceptively simple window bays on a Greenwich Village building conceals the deep attention to innovation, craft, and context.