August 25, 2010

Americans bring their “can-do” approach to Venice

The form of Duck-and-Cover produces the big box logo from a Google-Earth point of view, and a verdant garden at street-level, image courtesy RSAUD Starting this Sunday, August 29, when the Venice Biennale opens (and runs through November 21), there will be a lot of chatter about what feeds architecture and design thinking in 2010. […]

The form of Duck-and-Cover produces the big box logo from a Google-Earth point of view, and a verdant garden at street-level, image courtesy RSAUD

Starting this Sunday, August 29, when the Venice Biennale opens (and runs through November 21), there will be a lot of chatter about what feeds architecture and design thinking in 2010. Here, we’re kicking off the discussion with a look behind the scenes at the U.S. Pavilion. Its curators, Jonathan D. Solomon and Michael Rooks named their show Workshopping: An American Model of Architectural Practice. The title, they say, is meant to evoke our “can-do mentality”. Solomon, acting head of the department of architecture at the University of Hong Kong, for instance, starts his catalog essay by recalling the work of engineers who figured out how to save the Apollo 13 mission, urging architects to act as “initiators” who collaborate with other professionals to create a “charged atmosphere of solution-finding”. Could this be Horatio Alger meets Bob the Builder? No, it’s more like a call to action to solve some fierce, global problems: flooding, sprawl, lack of housing, poor access to fresh food and clean air. I spoke to Solomon and Rooks, who is Wieland Family curator of modern and contemporary art at Atlanta’s High Museum, just as they were about to fly to Venice to mount the show.

How do you define “workshopping”? How is that different from collaboration?

Jonathan D. Solomon We use the word workshopping to define architect-initiated collaborations that advance in the spirit of problem-defining as well solution-finding. This way of working privileges research, social engagement, and private initiative for public benefit. It empowers architects to take on the needs of the city. While workshopping, like all architecture, requires collaboration between multiple disciplines, it sees architects as initiators and leaders of these collaborations.

Why did you choose the particular participants? What aspect of their work fit the exhibition?

JDS We wanted this exhibition be a conversation, so we chose exhibitors who would be able to set off each other’s differences rather than take refuge in their similarities. We gathered a geographically, ideologically, and generationally diverse group who represent seven very different approaches to practice in the American city.

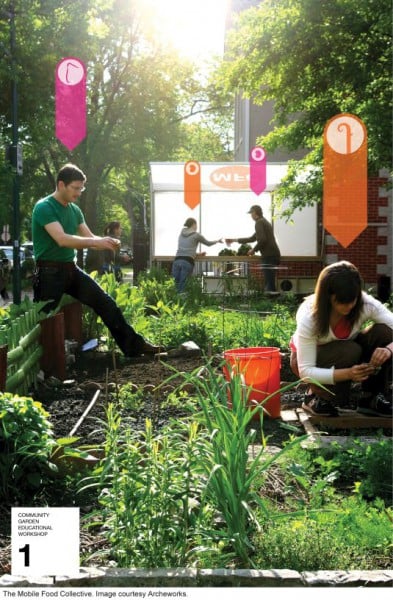

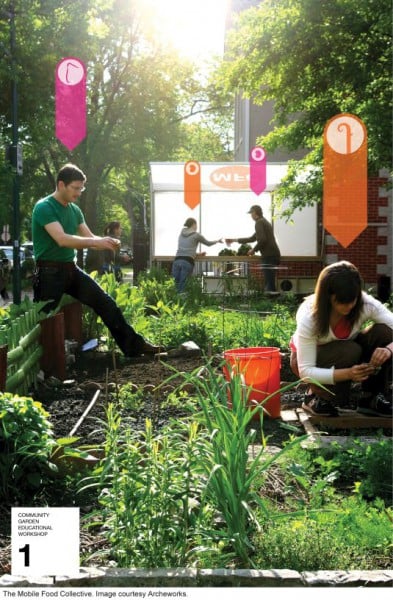

The Mobile Food Collective, Image courtesy Archeworks.

Michael Rooks ArcheWorks is the alternative design school in Chicago, New York’s Terreform is the research NGO founded by Michael Sorkin, and cityLAB is a UCLA think tank. They are examples of hybrid institutions that see the city as a territory for working out social and cultural problems of our day. The projects range in focus from resource management to social sustainability, from post-urban public space to affordable housing.

New York City (Steady) State, Terreform, New York, NY Michael Sorkin

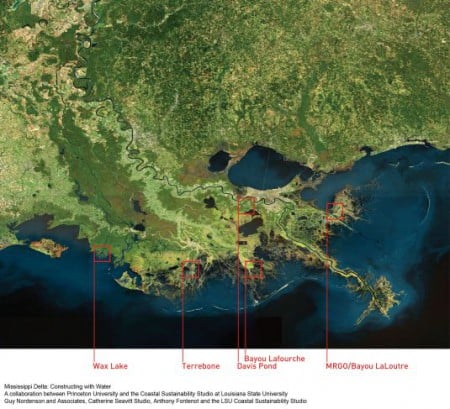

Guy Nordenson’s team of professionals and institutions from a variety of fields combines research, analysis, and design, which becomes the foundation for proposing solutions to rising sea levels in New York and New Orleans. Their collaboration, under the team’s leadership, transcends any one purview.

Mississippi Delta: Construction with Water: A collaboration between Princeton University and the Coastal Sustainability Studio at Louisiana State University Guy Nordenson and Associates, Catherine Seavitt Studio, Anthony Fontenot, and the LSU Coastal Sustainability Studio.

John Portman & Associates epitomize the model of a practice where the architect acts as designer and developer. By working in both public and private spheres the Portman office has been able produce truly transformative results like bringing their home city, Atlanta, into the 20th century. More importantly the model of space the firm invented in the 1960s—the continuous private interior for public use—has in this century become a model for development worldwide, especially in Asia.

Peachtree Center, Atrium Interior Copyright 1985 Jaime Ardiles-Arce

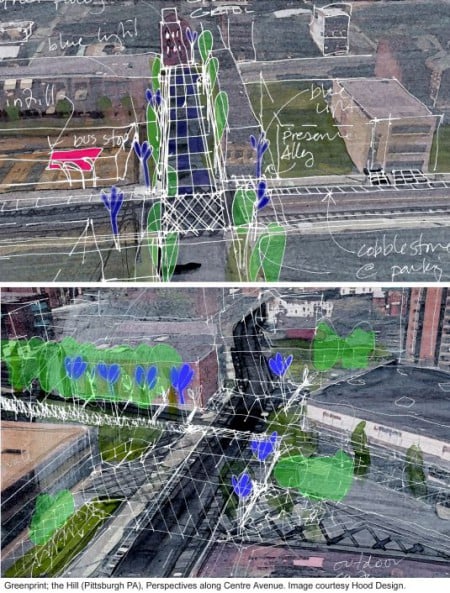

JDS Walter Hood runs a small landscape architecture firm in Berkeley along principles of community participation, while maintaining the authorship and expertise of the architect. His approaches are radical; we are showing a model that his office built to be carried out into the site so that anyone passing by could leave comments on post-it notes. Then the model comes back in and new iterations are prepared.

Greenprint, the Hill (Pittsburgh, PA), Perspectives along Centre Avenue. Image courtesy Hood Design.

MOS, a young and dynamic office from New York City, is engaged in rethinking architectural solutions from the ground up. Asked to conceive an installation for the pavilion’s open courtyard that would encourage social interactions, they proposed a canopy of reflective Mylar balloons tethered to nylon straps. Like their installation at PS1 last summer, the Biennale’s Instant Untitled envisions not only new structures and uses for materials, but new ideas about what public space in the city can be: temporary, a little precarious, ecstatic.

Rendering of Instant Untitled, a new site-specific installation for the courtyard of the American Pavilion at the 12th International Architecture Biennale. Image courtesy of MOS.

MR What binds these diverse practices together is a shared conviction and commitment to better the city, and shared willingness to re imagine the practice of architecture, if necessary, from scratch.

Christopher Hawthorne (one of cityLAB’s board members) recently wrote an essay called “ On Credit” in which he points out that many architects refer to the importance of “collaboration” but, at the end of the day, are not at ease sharing the limelight. Would you say that Hawthorne’s assessment is an accurate one? If so, is it one that’s changing?

JDS I would be inclined to turn this around and say that architects need to be even more aggressive about being recognized for the work they do, especially when in a collaboration. We need to respect our profession as the leader of the building industry, if we expect others to respect us. A basic principle of this stance is to insist on being recognized for our unique contributions. Workshopping requires architects to take responsibility for the solutions they propose. How can they do this if they are not recognized for the contribution they make?

MR For example, if you look at what cityLAB has brought to Venice, you’ll find a rich lineage (they call it their Operating System) for the architectural project mapped out on the wall: They document how the project was initiated, how is it supported, how is it researched, and eventually how is it designed. The architect is, and should be, identified among all the professionals in this process.

JDS This is another way in which we would differentiate workshopping from a typical collaboration, which tends to be accompanied by the flattening out individual contributions in order to recognize collective effort. We are very interested in the different forms of hierarchies that different forms of practices employ. To compare the cityLAB Operating System with the organizational charts for John Portman & Associates for instance, is fabulously illuminating.

Please explain what you mean by architect-initiator. Do you think an architect is better suited to be initiator of such collaborations than, say, an urban planner?

MR Our exhibitors include architects, landscape architects, engineers and academics. The kind of initiative we admire is hardly the province of architects alone.

JDS Architecture, by its nature, is collaborative, and architects receive one of the broadest educations available, which positions them well to work in this way. Architecture creates excellent conditions for workshopping but what really matters is the initiative.

How is workshopping American? Or how is it an American model?

JDS We are very sensitive about this title! In fact, in Venice, we are taking every step to open up our conversation to a global context, and we are finding a good degree of agreement amongst our colleagues that this type of work in the city can take place in North America much more readily than in, say, Europe or Asia. This is not to say that these practices could not flourish elsewhere, but they would have to overcome significant obstacles that conditions elsewhere—political, regulatory, cultural—may not be friendly toward.

MR It is our responsibility as curators not simply to select our country’s most talented or accomplished architects, but to put forward the proposition that the United States offers something unique to the global community. We humbly present workshopping in Venice as an American model, with the hope that the international community can benefit from the work we’re showing.

Angela Starita is a writer living in Brooklyn. She recently went back to school to study the work of architect Lina Bo Bardi.