May 9, 2012

Community-driven design with the other 90%

Photo by Architecture for Humanity Watching torrents of brown water cascade down the hill, filled with garbage and visibly eroding the rocky landscape, we were dramatically reminded of the importance of modern storm sewers. This humble piece of infrastructure, generally hidden from view, goes unnoticed during the course of our everyday lives in the United […]

Photo by Architecture for Humanity

Watching torrents of brown water cascade down the hill, filled with garbage and visibly eroding the rocky landscape, we were dramatically reminded of the importance of modern storm sewers. This humble piece of infrastructure, generally hidden from view, goes unnoticed during the course of our everyday lives in the United States, but on a hillside slum in urban Haiti during the rainy reason, there is nothing more important. From the perspective of public health, this regular deluge in the informal settlement of Villa Rosa is devastating, spreading disease, soaking possessions, and sometimes sweeping away entire buildings.

Photo by Architecture for Humanity

Villa Rosa is a dense hillside settlement of about 12,000 residents located at the edge of Port-au-Prince. In addition to the annual problems brought on by the rainy season, Villa Rosa was one of the areas worst hit by the earthquake of 2010, forcing many of its inhabitants into tent camps or homelessness. But while the earthquake was devastating, in the rebuilding effort there is an opportunity to build back better. Basing its efforts on community engagement, the Villa Rosa project team from Architecture for Humanity (AFH) plans to do just that. Architecture for Humanity is a nonprofit organization founded on the idea that only a small percentage of the world can afford architectural services, but it is the remaining population that needs them most. The Villa Rosa project is an urban redesign effort of broad scope, spanning mapping, community engagement, NGO coordination, planning, and design. The goal is to bring the economic and infrastructural benefits of planning to the hastily assembled hillside of Villa Rosa.

Villa Rosa began its current phase of existence in 1986 with the fall of the Duvalier regime. The exit of the government meant the end of suppressed urban migration, allowing squatters to occupy the recently vacated hillside next to Route Canapé Vert. Left to develop without regulation, the settlement has grown dense as newcomers build their homes on any and all unoccupied space. Pathways are the leftover gaps between buildings, rather than routes that preceded them, so circulation is an ever-changing maze of narrow footpaths. Thus it was mapping that began the Villa Rosa project, painstakingly walking the neighborhoods and entering the locations of significant buildings and roads by GPS. Parallel to this effort, the community engagement team began reaching out to local organizations, as well as connecting with other NGOs working in the area. One year into the project, this was the part of the effort we three graduate students from the University of Minnesota School of Architecture plugged into.

Villa Rosa Microplanning Guidelines, Architecture for Humanity

Prepared by Niko Kubota and Chrsitian Beauleiu

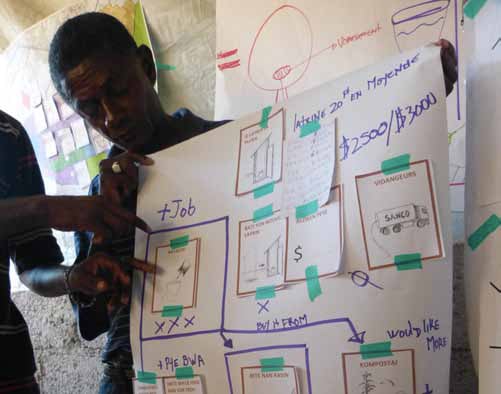

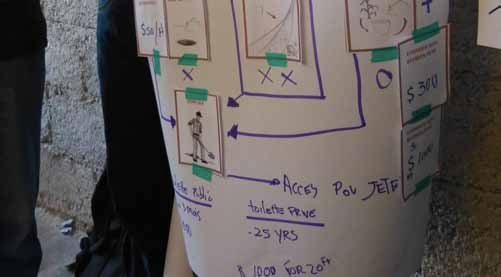

Community engagement is an integral part of the design process. While AFH and partner NGOs were mapping the different neighborhoods at Villa Rosa to locate damaged houses, paths, and water points, owners were rebuilding their houses on sites surveyed as vacant the day before. In this environment, feedback and direction from the community is vital to understanding what is happening on the ground. Thus a portion of the Villa Rosa team focuses on the design of community charettes to drive the design process for new infrastructure, from retrofitting schools, to water point construction, to drainage and path infrastructure. With the necessary tools to democratize the language of planning, the community is able to guide the rebuilding process.

Community Infrastructure Design Charette

Photos by Architecture for Humanity

Photo by Niko Kubota

While mobilizing and gathering community input, the Villa Rosa team must simultaneously digest this information and synthesize appropriate urban design interventions. Most concrete of these strategies is the design of effective drainage systems that incorporate small public spaces, seating, and plantings, but the project’s interventions go beyond physical infrastructure. Many of the problems endemic to Villa Rosa spring from the complex challenges of urban poverty. One example of this is the problem of waste removal. While in developed nations, municipal governments collect taxes and provide a coordinated system of waste collection, Villa Rosa lacks any kind of municipal government, much less taxes to support something less vital than food and transportation. In this kind of situation, the standard approach of planning needs to change.

Internally displaced persons camp in the middle of Villa Rosa

Photo by Architecture for Humanity

The community currently relies on a series of ravines that cut through the settlement to wash away all of the uncollected trash, but the sheer volume often overwhelms the few drains, clogging them and causing flooding. At locations without any manmade drainage, rain results in rapid erosion, destroying paths and collapsing houses. Water delivery is also difficult. DINEPA, a government agency, provides subsidized water at a few points in the north of the settlement, but these are available only once a week for a few hours, and carrying capacity is usually limited to one manageable 5-gallon bucket for the users who must transport all water by foot. The alternatives to this once-weekly service are a few small private businesses that sell water from their own wells or collect rainwater and sell it at a higher price.

A Villa Rosa water point, recycling collected for redemption

Photo by Architecture for Humanity

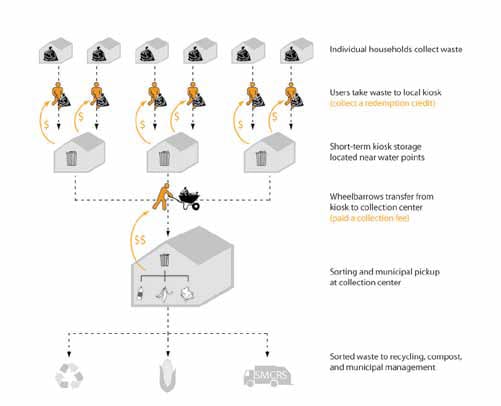

Behavioral change is vital to improving living standards (such as starting a culture of trash collection where it did not previously exist), but can be difficult to implement without government enforcement. Social science findings point to bundling errands as an effective method of changing behavior. At Villa Rosa, AFH is targeting water collection, an already necessary errand, as an opportunity to roll in a new trash collection regimen. The strategy is to build kiosks distributed across the settlement that would accept trash and sell water. As trash collection is not currently practiced, the combination of these activities makes it much more likely that a new habit can be formed, especially if a financial incentive for recyclables can be established. In this way, design is being used to make a comprehensive process that is based around the built structure of the kiosk, but goes beyond that into developing a new pattern of user habits.

Villa Rosa Community Action Plan Phase Two Report, Architecture for Humanity

Prepared by Niko Kubota

Villa Rosa Community Action Plan Phase Two Report, Architecture for Humanity

Prepared by Niko Kubota

We make up a small part of the team of planners and architects here, but the process feels right. Meetings and discussions across the team allow ideas from different parts of the process to interact and sometimes bleed into each other. Although the project is confined by the budgets and schedules of partner organizations, it is this collaborative effort that drives the Villa Rosa planning process, allowing it to move beyond a simplistic exercise in imposing Western systems onto a developing country. This is the kind of design process that we believe is paving the way for the future of the urban design discipline. It moves beyond the idea of a single master-planner creating “Radiant Cities” and “Brasilias”, to something more akin to medicine: examining, making a diagnosis, and then formulating a specific treatment appropriate to the patient. We hope that it will be this more humble, incremental approach to development that will begin to heal the maladies we will inherit from rapid urban growth of today.

Water and Sanitation Charette

Photo by Architecture for Humanity

Jessica Andrejasich holds a BArch from the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana; Niko Kubota at holds a BA from Bowdin College in sociology; Kristen Salkas holds a BA from St. Olaf College in biology and studio art. All three are second-year graduate students at the University of Minnesota School of Architecture and Volunteers at Architecture for Humanity, Haiti.