September 2, 2011

Duck and Cover

As David Monteyne’s fascinating volume, Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), makes clear, the most important thing to remember is that these structures were not meant to advertise blast protection. The Cold War generation of Americans first encountered them in elementary school, where the civil defense programs, as […]

As David Monteyne’s fascinating volume, Fallout Shelter: Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), makes clear, the most important thing to remember is that these structures were not meant to advertise blast protection. The Cold War generation of Americans first encountered them in elementary school, where the civil defense programs, as we later found out, seemed to symbolize only conjoined paranoia and feckless optimism, made all the more ridiculous when we learned about the palliative nature of duck and cover drills. They seemed to be saying that if the school building couldn’t protect you from Soviet warheads, a desk surely would.

The Office of Civil Defense (OCD), which spearheaded the fallout shelter program, made early distinctions between the notion of “fallout” and “blast” protection, but soon abandoned the latter aim as virtually impossible. By 1961, blast protection claims disappeared as multi-megaton nuclear bombs grew in number as did the knowledge of their effects. No, OCD never imagined that your school basement would, in fact, emerge unscathed from the mushroom cloud. “The basic premise of fallout shelter,” Monteyne writes, “is that the explosion of the nuclear bomb must occur elsewhere; there is no need to protect people from radiation if they were already vaporized at ground zero.” Presuming, no doubt correctly, that even a distant explosion would prove massively destabilizing, the fallout shelter program sought to establish central gathering spaces, stocked with supplies, which would offer some central refuge for the citizenry.

The proposal for public fallout shelters inspired initial opposition, though not for the reasons you might imagine. Congress repeatedly turned down requests for shelter funding, balking at the potential costs and the implications of central planning involved. So the OCD turned its efforts to encouraging private shelter design, producing considerable literature on how best to build them in backyards or basements. Yucca Flats proved a testing ground for shelter prototypes, which the OCD promoted to a variety of media. There is an element of the cartoonish to all this in hindsight, with the book’s photos revealing test sites not far removed from the model village in the opening of Indiana Jones and the Crystal Skull. Monteyne, while making clear that civil authorities were generally doing the best they could with the information they had, certainly appreciates the levity of these efforts, and regularly employs prose considerably more wry than anyone has a right to expect in a book about civil defense. In describing a shelter model, he notes, “In the foreground sits the crew-cut father, protecting the entry as it were; behind him, mother wears a dress and high-heeled pumps; their son seems to be smiling, knowing that the shelter was built according to data determined on ‘Doomsday Drive’ at Yucca Flats.”

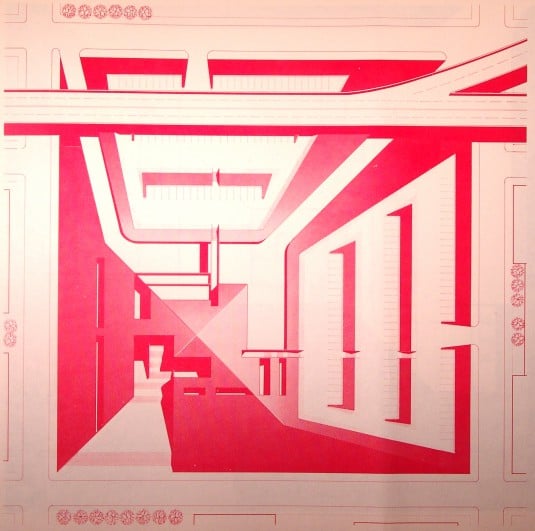

An intensive exercise in protective design at the University of Kentucky resulted in this pyramid-like fortress design. “Site plan of Charles Moore’s pyramidal city hall for “Tortilla,” designed for the charrette at the University of Kentucky. From Office of Civil Defense, City Halls and Emergency Operating Centers (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1965).

An intensive exercise in protective design at the University of Kentucky resulted in this pyramid-like fortress design. “Site plan of Charles Moore’s pyramidal city hall for “Tortilla,” designed for the charrette at the University of Kentucky. From Office of Civil Defense, City Halls and Emergency Operating Centers (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1965).

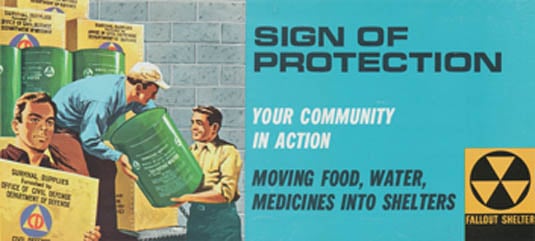

Congressional parsimony was overcome with the Kennedy administration, as the President announced the goal of “fallout protection for every citizen.” It was determined not to pursue a construction program, but to determine what existing infrastructure might suit shelter purposes, and a National Fallout Shelter Survey was commissioned in pursuit of this undertaking. The criterion for “shelter” designation was quite loose, with an inclination towards the subterranean and windowless but including plenty of locations that simply provided ample space. The OCD found a massive rate of compliance by the building owners they approached; one 1969 figure reported an 88% rate of participation; while 16 years earlier, by 1953, some 153,000 exterior fallout shelter signs were deployed. These cropped up in a wide range of buildings – schools, churches, office buildings, government facilities, among them. Participation wasn’t merely a question of accepting signage; it required building owners to “provide space for the permanent storage of water, high-energy crackers and supplements, and kits for sanitation, first aid, and radiological monitoring.” Stocking proved another considerable undertaking, drawing upon broad civic support; the government obviously provided the supplies, but businesses, fraternities, trucking companies, and social clubs volunteered to transport materials to countless basements.

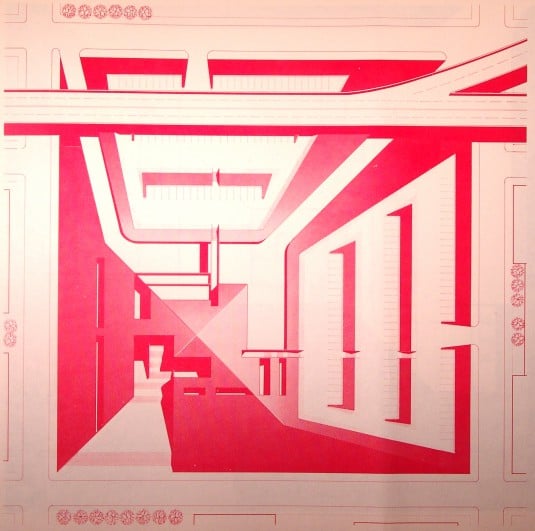

A prototype school project, constructed almost entirely underground. “Perspective of Abo Elementary School and Fallout Shelter, Artesia, New Mexico. Photograph courtesy of Byron Miller.”

A prototype school project, constructed almost entirely underground. “Perspective of Abo Elementary School and Fallout Shelter, Artesia, New Mexico. Photograph courtesy of Byron Miller.”

But the OCD program didn’t stop there. They sought to influence future designs in suitable directions, proposing a variety of windowless, squat, and subterranean schemes. In an effort to popularize them, the OCD approached the American Institute of Architects (AIA), which, seeing an opportunity to promote the stature of the profession, consented to host a design competition with school design as its first subject. The characteristics of the winning entries were not surprising. As Monteyne notes, “Most of the entrants that received awards betray bunkerlike characteristics, indicating the turn away from a glassy, open world architecture and toward more solid forms. For example, many of the entries feature massive bearing walls, enormous earth berms, and thick slab roofs as barrier shielding. In the representative grand-prize winning design by Ellery C. Green of Tucson, a professor at the University of Arizona, the shelter area is surrounded by an arrangement of almost windowless classroom blocks, which are buffered with giant planters and revetments.”

Two subsequent design competitions, for a shopping center and community center, produced results even more bunkerlike. In this, the OCD and AIA found themselves exerting pressure at a precisely fortuitous moment – that cusp between a window-heavy International Style and the rise of Brutalism. It’s difficult to determine precisely which influence this OCD nudge commanded in the private sphere, but its influence in the private sphere was distinctly palpable, and, as with any such government encouragements, its impact became a subject of outsized debate. Monteyne quotes the critic Lewis Mumford, from The City in History, “What began in the nineteenth century with the burial of urban architecture for function and aesthetics, had become in the nuclear age the burial of all urban activities: once the ‘authorities [had] sedulously conditioned their citizens to march meekly into cellars and subways for ‘protection’.” AIA’s critics, architects among them, challenged the implicit preparation for war that these efforts seemed to encourage, and the notion that nuclear conflict was, in fact, survivable. Manufacturers also took alarm. Builders of wooden homes, similar to those used in early nuclear tests, continued to maintain that their products could withstand fallout, despite ample evidence that their residents could not. Glass manufacturers feared this rising distaste for windows. One, Libbey Owens Ford, took out national ads extolling their product as “the one magic material that encloses without imprisoning.”

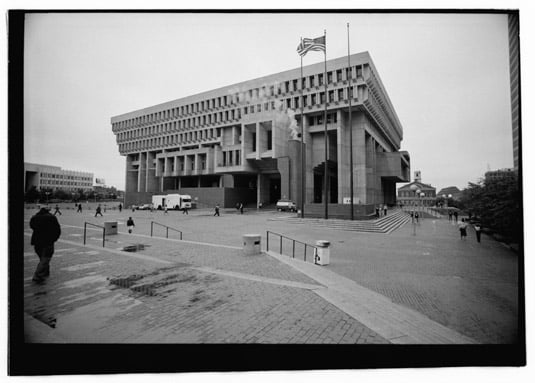

It’s no surprise that one of the most hated works of public architecture from the era – the Brutalist Boston City Hall – was one dearest to the OCD. The hulking structure was, in countless regards, an exemplar of design in accord with OCD criterion. While it was not explicitly designed for civil defense, “many aspects of fallout shelter were inherent to the bunker architecture of the building—its mass, overhangs, thick concrete waffle slabs, and the way it burrowed into the grade of the site,” notes the author. Boston City Hall actually contained the local civil defense office as well as large, sheltered gathering spaces, and a basement stocked heavily with OCD supplies (some of them still moldering there, as the author’s photos reveal), and about everything a civic architect could desire from public architecture – aside, fatally, from a knowledge of radiation drift which, in fairness, few understood well at that time.

Boston City Hall

Boston City Hall

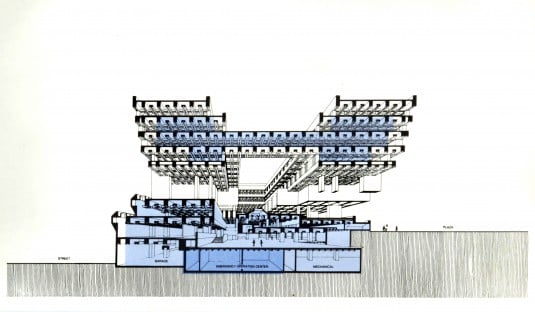

“East-west section of Boston City Hall. Emergency Operations Center in dark blue; fallout shelter spaces in light blue. From Office of Civil Defense, Boston City Hall/Boston Massachusetts: Buildings with Fallout Protection, Design Case Study 7 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1971).”

A rise in exactly this public understanding of radiation risks, not to mention staggering increases in missile payload amounts, contributed to a gradual withering of the fallout shelter program. Fallout shelters continued to be classified into the 1970s, though federal stocking of shelters ended in1969. Many supplies were removed in the mid-70s; hilariously, some of these long-in-the-tooth crackers were sent to Bangladesh as food aid. Fallout shelter signs began to fade into memory (a brief check confirmed plenty on sale currently on EBay).

The principles of design originally encouraged in the fallout shelter program are more than a mere memory, however. The OCD morphed into the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency in 1972, while the new Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) “republished (with minimal editing or new content) dozens of earlier technical reports, guides, and directives related to fallout shelter,” notes Monteyne.

FEMA architectural security recommendations continue to recommend design principles first established for fallout shelters; you can find ready examples of these continuities in civic architecture, from city office buildings to embassies. Monteyne’s fascinating look at this inglorious chapter in American history may be a cautionary tale. Those fading fallout signs are more than mere yellowing curiosities, they’re reminders that civil defense ideas, however sound at their inception, often don’t even have the shelf life of a cracker.

In the May 2011 issue of Metropolis, we told you about another book on this subject: Waiting for the End of the World

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He has written for The Wall Street Journal, City Journal, The Weekly Standard, and PopMatters on urban policy, cinema, historic preservation, literature, and higher education.