December 11, 2009

Loving Panton

For more than three decades now, two bright-orange Panton Chairs have graced my apartments in New York City. They started out in the living room, then migrated to the bedroom, and now they’re my dining chairs, to be seen clearly from every angle of my tiny downtown loft. And I love looking at them—their shiny, […]

For more than three decades now, two bright-orange Panton Chairs have graced my apartments in New York City. They started out in the living room, then migrated to the bedroom, and now they’re my dining chairs, to be seen clearly from every angle of my tiny downtown loft. And I love looking at them—their shiny, smooth, sensual plastic forms, their striking Sixties color, their generous seat pans from the front, sleek profiles from the side, and humanoid bottoms from the back please my eye endlessly. Believe it or not, I also enjoy cleaning them—going over the smooth plastic with a damp cloth, then buffing it dry is a satisfying moment, in contrast to my other furniture, which needs vacuuming, dusting, and sometimes toxic stain removers. My Pantons, in fact, stand in defiance of complex maintenance. They are truly Modern chairs in this regard too. And reports to the contrary, my Pantons did not throw guests across the room, break under them, or in any way cause discomfort or bodily harm to anyone. As far as I’m concerned they’re ergonomically, sculpturally, materially, and aesthetically perfect.

As someone who sometimes teaches design history, I also appreciate the chairs’ breakthrough design and materiality, product engineering, and manufacturing methods. The Panton, after all, is the first chair made of one piece of material, a process that took many years and many trials to develop and perfect, starting in the early 1960s. Knowing these historic facts also increases my appreciation of the chairs. And understanding that many trials and errors go into innovative products reminds me that design breakthroughs are not about “aha!” moments, but a sustained commitment to an idea.

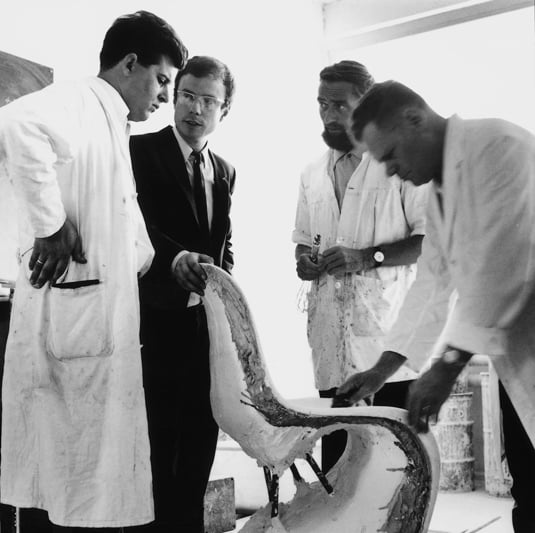

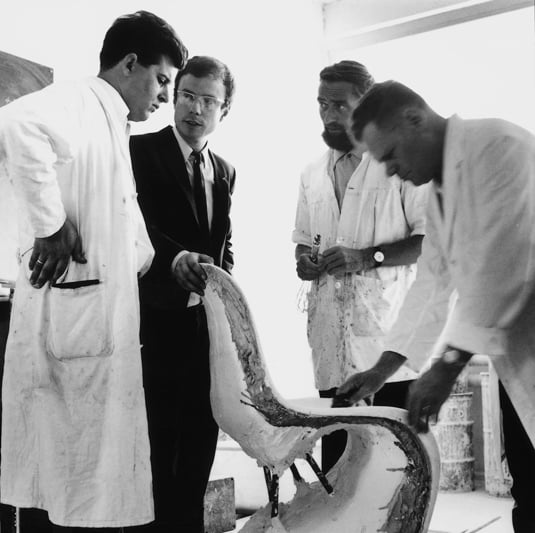

A Panton Chair prototype, from 1966

A Panton Chair prototype, from 1966

The first Pantons were made of hand-laminated, fiberglass-reinforced polyester by Vitra in collaboration with Herman Miller and saw the light of day at the Cologne Furniture Fair in 1968. But the process required a great deal of hand work and the chairs were way too heavy to stack, as Panton envisioned them. A new material, polyurethane hard-foam, was tried next, making mass production possible, though there was still a considerable amount of spackling, sanding, and painting required to give it the sleek, Modern feel the designer was after.

Then came, what seemed at the moment, the perfect material, a thermoplastic polystyrene (Luran S) developed by BASF, with properties that allowed injection molding, which aided efficient production. Though these chairs were made of liquefied pre-dyed plastic granules, they still needed processing after they came out of the molds. And because injection-molding technology at the time could only produce a uniformly thick shell, the chair’s stress points had to be reinforced by thickening its sides, and placing a kind of rib structure under the seat. These are the chairs I own, not the most recent models made of polypropylene, which have a matte surface but weigh less than mine do. I like my shiny chair better than their most recent incarnation.

On its 50th anniversary, the Panton Chair provides a record of material discovery and refinement. These chairs were made when plastics, as Dustin Hoffman’s Ben Braddock learns in The Graduate, were the future. Well, my plastic chairs have survived the future, along with lots of body types and sizes, and look as fresh today as they did when I first got them for ten dollars each, at a sample sale from Herman Miller. In the intervening years they have become an internationally-known design icon, and my personal design icon. I love their form so much, I even own several miniatures of them, produced by the Vitra Design Museum. What’s more sustainable than that?

.

Panton Chair photo, Marc Eggimann/© Vitra (www.vitra.com); archival photo, © Vitra (www.vitra.com), 1966