December 8, 2010

My Robot

Deep in suburban southern California, the future of architecture has already arrived. This future is not just about more complex forms and compound geometries. It is not simply about software but how to make what is generated with software a reality. It is about processes, ways of working, and materials. It is also about more […]

Deep in suburban southern California, the future of architecture has already arrived. This future is not just about more complex forms and compound geometries. It is not simply about software but how to make what is generated with software a reality. It is about processes, ways of working, and materials. It is also about more control for the architect. This is what Guy Martin had in mind when he started his own firm.

Guy Martin Design is quite possibly the most famous firm you have never heard of. He’s the guy who figures out how to make some of Philippe Starck’s more complicated creations, translating the digital into the physical.

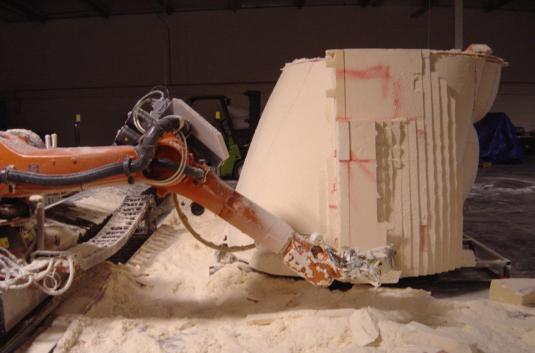

He works behind the scenes in a non-descript warehouse with no windows. Thankfully, he has a huge ventilation system. He spends most of his time here with Marie, his robot accomplice. He’s moved up in the world. He used to operate out of a shipping container (also without windows) in the parking lot of SCI-ARC—until he graduated and was asked to leave and take his container with him.

Guy Horton: What was your motivation for starting a design firm based on robot technology and in-house fabrication? You were trained in architecture. Didn’t you hear that architects are supposed to draw stuff?

Guy Martin: Yeah I did not get that memo. In fact I find a lot of richness and potential in being very close to the means of production and the materials. It is a dialogue that the profession has shied away from. There was a time when a sociological need was met by distancing the profession from these two issues, but I believe that this no longer serves the profession. With these technologies and methods we can remove that barrier and regain some of the control and craft that the architect used to have when he was master mason. It is an emphasis on demonstrating concepts and having to wrestle with the resistance materials and methods expose to us in the process. Removed from having a hand in the craft and being somatically distant from the materials and methods we are not witness to the expressive potential inherent in these steps of design. I am more interested in working at reintegrating these concepts back into the architectural process. There is also the desire to push the automation of building so that the built work can economically allow for material expressiveness. Then there is also the concern of re-integrating more craft into building through digital means.

GH: Where are these tools and processes more commonly employed?

GM: There would be two sets of tools one computational and the other would be analogue equipment. The computational tools would include laser scanning, FEA tools, haptic force feedback devices, scripting, etc. The analogue would include not only the robot but also hardcoating and extrusion machines, automated fiberglass deposition, automated spraying, laser trackers, and assorted automated tooling. These types of tools are found in aerospace, manufacturing, automotive, and prototyping industries.

GH: You can definitely work full scale for architecture applications. Why have architects not been using this technology more when their digital designs could be realized by it? Are they still thinking too traditionally about how things are made?

GM: On one hand it goes back to the first question, a lot of architects don’t have a good understanding of how the materials and methods work so they do not know how to write specifications for it. In some ways they do not know how to push it through the bidding, contracting, and approvals process. This varies with the materials being used. Composites, as in thermoset resin and fiber composites, have a great potential to change this. There are efforts under way to allow for these materials to be more readily accepted by governing agencies. The International Building Code has pending changes that will allow manufacturers to be certified in a way that architects can more easily specify, say, a facade system or column cladding system composed of composites. This will allow architects to work more closely with manufacturers or design-build companies specialized in the architectural application of composites. This may allow skins to become accepted structural components, which would free designers from the present section and loft strategy used to achieve compound curved surfaces. Architects and builders are also not aware of economies of achieving this. (Just look at how much of the new super planes that are composed of composites.) It is also important that with this change the design-fabricator be involved early on in the process to assist the designer in realizing the desired design intent, with efficient production methods.

Parris Landing, Boston, light bulb and duck sculptures. Photo courtesy Guy Martin Design.

Parris Landing, Boston, light bulb and duck sculptures. Photo courtesy Guy Martin Design.

GH: What is the most complicated thing you have ever been asked to produce?

GM: Complicated politically would be the column covers for Philippe Starck. Complicated time-wise would be the “Green Lantern” prop project.

GH: As far as I know, you are the only person doing this with the largest and most advanced robot available. Some people use much smaller robots. Does size matter?

GM: Size matters in terms of economies of scale. We are limited right now more by transportation—by the size that can fit on a flat-bed with the wide-load limitations on the highway. The more components you have to make the more time is spent in fabrication, installation, and planning. So it does afford economies of scale. We can do a run up to 80 feet in length, which can later be broken down for shipping saving a large amount of setup, fit and finish, and programming time. Additionally we are set up to automate downstream applications, such as finishing, which furthers these economies.

![]() Icon Brickell, Miami, column enclosures. Photo courtesy Guy Martin Design

Icon Brickell, Miami, column enclosures. Photo courtesy Guy Martin Design

GH: What are the applications for architecture that you think this is right for? What could this make more efficient or cost-effective?

GM: Facade systems, column enclosures…starting with expressive elements in architecture then heading towards combining structural and expressive elements.

GH: How did you land Space X (America’s first private-sector space transport company, founded by PayPal co-founder Elon Musk)?

GM: Word of mouth.

GH: Where would you like to take this operation in the future?

GM: Digital craft…being the master mason of the digital age.

GH: You obviously have to know more than architecture to run this thing. What have you had to learn in order to do this and what is your background? Did you always think you would end up with a robot for a partner or were you planning on being more of a traditional architect?

GM: A better understanding of material science, chemistry, business management, in some ways being what the name architect actually means… to be in charge of and synthesize all these elements that go into the production of the built work: so additional work in engineering, additional time in sweating over actually conducting all of the steps on a large scale. Production methods.

I always wanted to find a way of being closer to the conversation that material and process afford….I have always been more interested in this…kind of like great cooking…you can talk about concepts all day, but the execution brings the intrigue to the table. I have always been interested in this. Digital craftsmanship just brought it to another level. But the robot is just another tool…you still have to be grounded in the analogue world to see the concepts through. It is that great intersection of the very old and the very new that is exciting to me.

GH: One last thing. Why did you name your robot Marie?

GM: From Marie Leveau the voodoo priestess from New Orleans of the 1800’s. My mom named her that as she would see me enter codes in the office and watch as Marie came to life. It appeared to be magic to her.

Guy Horton writes on architecture for The Huffington Post. He is a frequent contributor to Architectural Record, The Architect’s Newspaper, and author of The Indicator, a weekly column on the culture, business and economics of architecture, featured on ArchDaily. He is based in Los Angeles. Full disclosure: Horton worked with Guy Martin in the past. Follow Guy on Twitter.