November 16, 2011

Preparing for Earthquakes

The cracks in the Washington Monument seen on the day after the 5.8-magnitude earthquake. Photo: Matt Mcclain for The Washington Post Every week, it seems, we’re reading about earthquakes—both in faraway places where we’ve come to expect them, but also here at home. Earlier this month a dozen tremors struck 45 miles due east of Oklahoma […]

The cracks in the Washington Monument seen on the day after the 5.8-magnitude earthquake. Photo: Matt Mcclain for The Washington Post

Every week, it seems, we’re reading about earthquakes—both in faraway places where we’ve come to expect them, but also here at home. Earlier this month a dozen tremors struck 45 miles due east of Oklahoma City, with a 5.6 magnitude the most intense among them. Weeks earlier, the quake-prone Bay Area was put on edge by a series of tremors. And in August, Manhattan subways screeched to a halt and cracks surfaced in the Washington Monument as the East Coast got a rare dose of seismic activity.

While they rattled nerves, none compared to the devastating earthquake that struck Eastern Turkey late last month and again late last week, with the death toll having surpassed 600 and thousands of homes destroyed. Christchurch, New Zealand, was rocked by similarly destructive quakes and countless aftershocks in June. Finally, at a whole different scale, we saw the quake and resulting tsunami ravage Japan in March, not to mention the 2010 earthquakes that leveled parts of China and Haiti.

The aftermath of the Christchurch earthquake, photo via nhne-pulse.org

The aftermath of the Christchurch earthquake, photo via nhne-pulse.org

As an architect, it’s humbling and heartbreaking for me to accept the sad fact that earthquakes don’t kill people; buildings do. Recently the Campaign for Safe Buildings symposium, sponsored by the Yale School of Architecture, brought together architects, attorneys, planners, policymakers, scientists, and even longtime Fugees band member and Haitian activist Pras Michel to wrestle with that fact. Convened and funded by The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, the event was not the kind we often see sprout up immediately after natural disasters—be they earthquakes, hurricanes, tornados, or tsunamis—but instead one focused on the long-term, big picture.

It’s not enough for us to focus on natural disaster response only in the wake of one. We need to be proactive and ready. Thomas Fisher, Dean of the College of Design at the University of Minnesota, advocates for 10 public health innovations and policy solutions, ranging from the use of social media—increasingly a hallmark of post-disaster recovery—to the legalization of land and “socially-enforced” building standards, particularly in parts of the world without government-enforced building codes. According to Fisher, “The Emergency Events Database estimates that natural disasters have killed over 100,000 and rendered homeless over 200 million people each year since 2001, with an estimated annual impact of approximately $90 billion annually.”

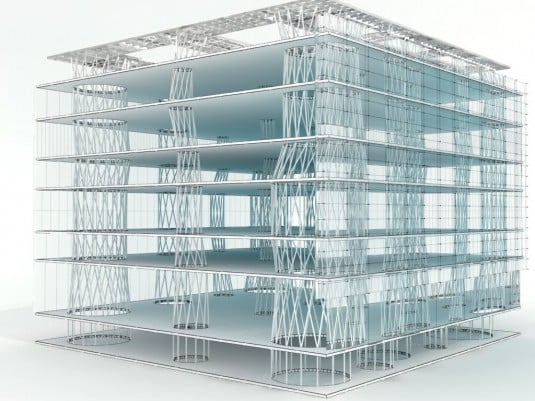

The structure of Toyo Ito’s Sendai Mediatheque, which sustained no major damage during the earthquake in Japan.

The structure of Toyo Ito’s Sendai Mediatheque, which sustained no major damage during the earthquake in Japan.

We need to understand that building codes and even structural reinforcement may help save lives, but none guarantee that buildings remain functional after the fact. Drawing on footage of the recent earthquake in Japan, Berkeley professor Mary Comerio used a picture of a brand new building by famed Japanese architect Toyo Ito to illustrate the reality of such codes. The interior of the building was visibly destroyed, literally mangled, but the structure itself stood. It thus succeeded in providing the basic level of life safety intended by codes. That said, it no doubt remained a client and insurer’s nightmare, and would require a full gutting, if not a complete rebuild. And this was, remember, one of the most sophisticated buildings in Japan.

Video shot on the Sendai Mediatheque’s seventh floor, showing the building withstanding the violent quaking.

We need to invest in earthquake preparedness here at home, particularly in highly populated, highly seismic areas. Japan has done exactly that through building code enforcement, earthquake preparation, and even early-detection efforts and warning systems, according to Karl Kim of the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center. Motivated by the 1995 Kobe earthquake, Japan’s investment has been on the order of $1 billion annually, significantly more than the U.S., for a country a fraction the size.

We need to acknowledge and address the unique, earthquake-related risks facing informal settlements around the world. The United Nations estimates that 1 billion people live in such settlements today, and that number is expected to double by 2030. Whether they’re in Haiti, India, Iran, China, or elsewhere, these squatter communities are particularly susceptible to earthquakes and other natural disasters. Many sit at the cross hairs of the tectonic plates that spawn earthquakes.

This is very much the case in Bogota, Colombia, according to architect Rodrigo Rubio Vallert, where the populations of informal settlements have skyrocketed from 400,000 to 9,000,000 over the past 50 years. Its largely unenforced building codes were adopted based on U.S. codes, circa 1984. But Bogota has excelled in another way: by legalizing many informal settlements, through land ownership transfers and other measures over the past decade. We have seen the same elsewhere around the world, pioneered by groups such as the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights across Asia and Grupo Terra Nova in Brazil. The re-titling or re-deeding of land paves the way for stronger codes for buildings themselves.

Minor as they may be, the Oklahoma and East Coast earthquakes provide a wake-up call that even parts of the U.S. with imperceptibly low levels of seismicity are subject to the Earth’s shifting. Meanwhile, countries with massive informal settlements need only look at the ongoing suffering in Haiti as well as the successes in Bogota for motivation to improve their building codes. Yet perhaps the most crucial and dignifying innovations of all, with ripple effects for communities and governments, are efforts to legalize land. They represent a crucial, proactive step toward safer buildings and lives saved.

John Cary is the editor of PublicInterestDesign.org and author of The Power of Pro Bono: 40 Stories about Design for the Public Good by Architects and Their Clients. He writes and speaks widely on architecture, design, public service, and social justice.