January 9, 2012

Project Haiti: Part III

Jeffrey Boyer, a mechanical engineer in HOK’s San Francisco office, describes Project Haiti as a “three-dimensional textbook”. Indeed, our design team hopes that exposing users to the building systems will help them understand the structure’s purpose, maintenance, and importance. Beyond this educational purpose, I think of Project Haiti as a three-dimensional storybook. It is the […]

Jeffrey Boyer, a mechanical engineer in HOK’s San Francisco office, describes Project Haiti as a “three-dimensional textbook”. Indeed, our design team hopes that exposing users to the building systems will help them understand the structure’s purpose, maintenance, and importance.

Beyond this educational purpose, I think of Project Haiti as a three-dimensional storybook. It is the story of survival and perseverance, of rebuilding and restoring. It is the story of Haiti itself.

In the most literal sense, we are rebuilding an orphanage and children’s center that was damaged by the 2010 earthquake. The new building will be designed to meet seismic requirements and be fully self-sustaining for daily use as well as in emergencies.

It will symbolize the rebuilding of the construction industry in Haiti, the post-disaster restoration of the local economy and, most significantly, the restoration of child health and the perseverance of the Haitian spirit. These are lofty claims for a 6,000-square-foot building to make. Yet, when you see the work that Gina and Lucien Duncan have already done in their Fondation Enfant Jesus campuses, you will know that if anyone can transform Haiti, they can.

Fondation Enfant Jesus’ sprawling property in the region of Lamardelle houses a clinic, an orphanage, a kitchen, a school for kids from the surrounding community, and guest quarters for visiting adoptive parents. A separate community serves women who became amputees after the earthquake; there they take care of one another and learn useful career skills. Aside from classrooms, the school contains a library, a sewing room, and a distance-learning computer room. When I asked Lucien what they planned to do next, he replied that his wife, Gina, wanted to work with elderly people. Of course!

Existing Computer Lab (top) and Library Facilities at Lamardelle (bottom)

Existing Computer Lab (top) and Library Facilities at Lamardelle (bottom)

When families arrive at the Project Haiti site, the children are often badly malnourished and dehydrated. They spend their time recovering their health and strength. We intend to make this stay as welcoming and pleasant as possible by designing a fun, safe, and playful environment. To do this, we have taken cues from items that we all loved as children: toys.

Simple Mechanical Toys

Simple Mechanical Toys

Mechanical toys are a great inspiration for much of what we are trying to accomplish with the design. They are simple – users can clearly see the mechanics of how these toys work. If something breaks, it is easy to find the problem and to understand what needs to be done to fix it.

Simple toys do not need a complex manual – they are human-powered. People of all ages and abilities can make them work intuitively. Using an uncomplicated set of mechanical principles – turn, twist, push, pull – these toys come to life, bringing delight to the user.

Mechanical toys are whimsical and fun. They serve little purpose other than to amuse their users. Often depicting brightly colored animals and storybook characters, toys like these are pure whimsy, genuine lightheartedness.

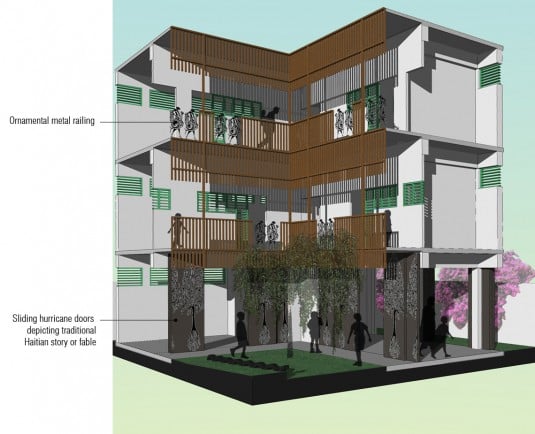

To be simple, human-powered, and fun we believe our building should function like a mechanical toy. It should be relatively easy to construct and maintain using methods that are easy to teach. The building should allow for occupant-controlled settings to adjust levels of light, ventilation, and security. Lastly, this project – as a place for children – should be fun and inviting. The design needs to be welcoming and familiar while encouraging interaction. After all, as I mentioned in my first Project Haiti blog post, kids want to play!

This element of play is what I have been studying most in my work on the project. How can we create a place that instantly intrigues children, even at a time when they are scared and vulnerable? How can we infuse cultural iconography into the architecture to create a warm, familiar environment for them? Creating a wholly sensory experience – sights, sounds, smells, tactility, even tastes – will make a difficult transition that much easier.

Project Haiti Section Showing Child-Friendly Characteristics

Project Haiti Section Showing Child-Friendly Characteristics

And what of the allegorical living storybook? Stories are cultural and culturally ubiquitous. Even those who cannot read know of the tales and fables that have been passed down through oral history for generations. By integrating elements of these stories into the building and the landscape, we can instill a sense of knowledge of the place in this new environment. The quality of “knowing” can help ease the fear and uncertainty of the families who come here.

For now, my work on Project Haiti is about the frivolous, the fantastical, and the fable–I look forward to reading many them.

Sarah Weissman graduated from Binghamton University with her BA in English and from Washington University in St. Louis with her Masters of Architecture and Masters of Urban Design. She is an architect at HOK where she is also the director of HOK IMPACT, HOK’s firm-wide strategic approach to Corporate Social Responsibility. She lives in St. Louis with her partner, Steve Dirsa, and their two furry kids, Porter and Champ.

Previous Posts:

Bienvenue a Haiti!

Project Haiti II