May 18, 2012

Q&A: Nina Rappaport

Vertical Urban Factory Exhibit, Photo by Christopher Hall After a six-month run in New York City, Vertical Urban Factory, curated by Nina Rappaport, opened on May 11th and runs through July 29th at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD). A longtime fan of the process of making things and the buildings that contain the […]

Vertical Urban Factory Exhibit, Photo by Christopher Hall

After a six-month run in New York City, Vertical Urban Factory, curated by Nina Rappaport, opened on May 11th and runs through July 29th at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD). A longtime fan of the process of making things and the buildings that contain the manufacturing occupations, as well as of Nina’s exacting and thoughtful research, I took the opportunity to the talk to the curator about the past. But as important, we discussed the present and future of manufacturing in urban neighborhoods. We also got into the new ways of making things that require none of the toxic smokestacks that loomed over the 20th century. After Detroit, Vertical Urban Factory will travel to the Toronto Design Exchange (September 12, 2012 to January 3, 2013).

Vertical Urban Factory Exhibit, Photo by Christopher Hall

Susan S. Szenasy: What made you choose the urban factory as the subject of your research, and what did you hope to find when you started out (when)?

Nina Rappaport: I have been fascinated with the role of the factory as workplace, part of the urban landscape, and a significant place of innovation in design since I was young. I remember visiting the Volvic water bottling plant in France and being intrigued with the process, the volume, the people who make things, the repetitive motions, and the creations that result. Then the architectural historian and urbanist, Reyner Banham’s Concrete Atlantis sparked an interest in the role of the engineer in the design of factories and the way in which Modern architects gravitated to the rawness of the innovative spaces of production. This actually led to my book, Support and Resist, on the role of contemporary engineers in design. I begin the book by discussing a Modern factory in Germany. All the while I wanted to return to the research I had begun on factories, some actually for a Metropolis article in 1995 on the fate of Albert Kahn’s factories on the 100th anniversary of the firm!

The factory as urban landscape and as part of a “spatial product” in the terms of Henri Lefebvre, contributes to the city in a different way than the office as a workplace did–shuffling paper all day but not making anything. And that led me to investigate how the processing and company organization as well as labor issues impact the design of the space.

And now I am drawn to these abandoned factories like a magnetic field of movement in the rust belts of the world; their historic structures the ruins in and of globalization. But what is the potential for a new kind of industry? Still of making things, but perhaps in a different way—both more hands-on and more robotics? How can it still be an urban situation smaller-scale and flexible production?

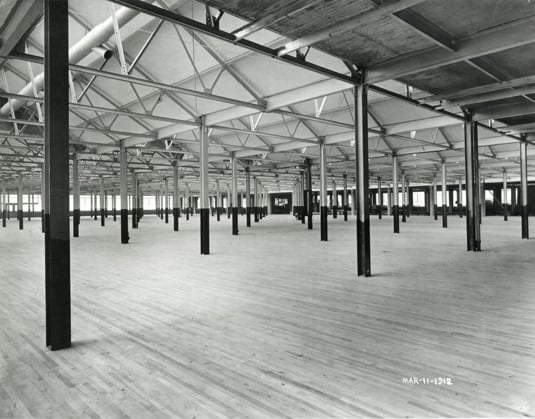

Continental Motor Car Co Interior

12801 E. Jefferson Ave. Albert Kahn and Ernest Wilby, 1911. Photograph courtesy of Albert Kahn Associates

SSS: Talk about how you saw your subject when you first exhibited your findings at New York’s Skyscraper Museum in 2011 and how you see your subject now in the Michigan context (one of the last remaining U.S. regions where manufacturing is still vital) as you installed the show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit, for its May 11th opening.

NR: The difference is interesting and relates to real estate and population density and of course white flight from the city of Detroit decades ago. New York has been envisioned a canvas for real estate development. How to turn all this valuable land into high-end development for a larger tax base? So the abandoned factories have been renovated into other uses. SoHo is a prime case of revitalization into other uses.

In Detroit, the factories are, for the most part, vacant. Many historic ones, such as Packard Plant are in a situation that preservationists call “demolition by neglect.” They are the canvas for graffiti artists and place for metal scavengers to reap their harvest. But as this is a shrinking city, very few are being renovated, so when one does see that glow of light in a former factory it is encouraging. And there are some as I discovered.

Packard Plant overview

5857 Concord Street. Albert Kahn and Ernest Wilby, 1903–05. Photograph courtesy of Albert Kahn Associates.

Packard Plant Packard Building 10 Exterior

5857 Concord Street. Albert Kahn and Ernest Wilby, 1903–05. Photograph courtesy of Albert Kahn Associates.

Packard Plant Today

5857 Concord Street. Albert Kahn and Ernest Wilby, 1903–05. Photograph by Nina Rappaport

Detroit is now seen as “beyond industry,” as the city of the future without it. But my view is still of cities as places of production. There are new ways to do this with maker spaces, educational programs, but the need for investors still remains. It might have to be more entrepreneurial and will, of course, take individuals as it did in Detroit’s heyday. My exhibition at MOCAD is paired with a local show, Post-Industrial Complex, which includes inventions and crafts from local makers and artisans. We are in an interesting dialogue and will have a panel discussion on June 2.

Omnicorp Hacker Space

1501 Division Street, Detroit. Photograph by Nina Rappaport

SSS: As Albert Kahn’s famous Highland Park factory for Henry Ford (built in 1909) defined the ways and means of American industrial might, what will the 21st century urban factory define?

NR: The 21st century urban factory could define what I see as clean, green, light, sustainable, networked, smaller, and integrated with the city. In other words, if in former industrial strength cities there is no heavy industry it can return to cities in a different form, vertical and dense and lighter. We also need to think about what we can produce locally to make cities more self-sufficient as well as continue to export.

Industry can now also be ecological–an urban industrial symbiosis where one company’s waste becomes the others energy source; where one company’s scrap metal is repurposed by another. This symbiosis has not been tried in cities, so opportunities abound. Kalundborg, Denmark is still one of the few areas where there are successful operational collaborations. There are other examples of eco-industrial parks but most of these are outside of cities. It has to begin with the companies working together and city agencies providing the support. Not easy when most industries are secretive and don’t share. But I am working towards this idea with experts in the field.

Highland Park factory, photo by Nina Rappaport

Vertical Urban Factory Exhibit, Photo by Christopher Hall

SSS: Have the architects and urban planners you engaged with for this project helped you in thinking about the new, sustainable, urban factory? How?

NR: Yes, there is a great deal of interest, but we need more rigorous examination of the issues and a new focus. And of course it is not just in the US, but in every former industrial center. Interestingly in NYC I am working with a few city officials who are now putting industry on the agenda, while NYC City Planning is not. Plant owners need to see the value that architects can bring in terms of sustainability, building efficiency, and the reuse of existing buildings. Cities need to provide tax incentives the way Export Processing Zones do in Asia.

Piquette Plant

411 Piquette Street. Field, Hinchman & Smith, 1904. Photograph by Nina Rappaport

SSS: Does the example of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, occupying the reclaimed ship yards, with its small workshops of skilled workers, start to define 21st century urban manufacturing, as mass production and distribution defined 20th century manufacturing?

NR: I constantly use the Navy Yard to illustrate the potential for urban sustainable manufacturing. The interesting thing is that there are very large-scale factories still there—sugar substitutes, glass-concrete, photo labs, as well as small workshops including a distillery. The scale is fantastic and the place is humming with activity. It can be considered as a holistic entity since it is operated by a private-public partnership. This allows them to develop infrastructural ideas for sustainability such as recycled wastewater, wind-powered lights, and reuse of water transport. I think it can go even further as an official ecological industrial park and a case study that can be replicated elsewhere.

The companies are also committed to their employees, which is significant as compared to workers in China or other subcontracted factories that are outsourced heavens. The inventors and workers innovate together. There is pride in their work.

SSS: What can the presence of the vertical urban factory, now that it’s no longer a smokestack industry, bring to city life, community, and economic development?

NR: It allows manufacturing to participate in creating a vital new economy for cities while still acknowledging the small-scale of new high-tech or biotech industries. There can be vibrant work/make/live scenarios with streets alive all times of day with different cycles of activity. Factories can be integrated in neighborhoods, provide training centers for skilled workers, and be incubators for business such as the food entrepreneurial center in Long Island City. Pride in one’s area of work would also play a part in city life and a sustainable economy.

Vertical Urban Factory Exhibit, Photo by Christopher Hall

This post was amended on 5/18/2012 at 4:04pm EST.