June 20, 2012

Re-imagining Infrastructure: Part 5

Small is beautiful. But for oyster-tecture, small isn’t the goal. It needs to be built at the continental-scale. Yet the beauty of small oyster-tecture projects is that they are inexpensive, easy to set up and manageable on a community level. Funding opportunities are available to sustain small community-scale efforts. And since lots of people love […]

Small is beautiful. But for oyster-tecture, small isn’t the goal. It needs to be built at the continental-scale. Yet the beauty of small oyster-tecture projects is that they are inexpensive, easy to set up and manageable on a community level. Funding opportunities are available to sustain small community-scale efforts. And since lots of people love bivalves, volunteers abound. The drawback is that those qualities that make oyster-tecture inexpensive and easy to execute are not easily scaled up for bigger installations. That said, it is not impossible to enlarge an oyster-tecture project while keeping the cost down, growing the support around it, and maintaining its ecological and design integrity for local needs, urban design, scientific discovery, and the goal of reestablishing a metapopulation.

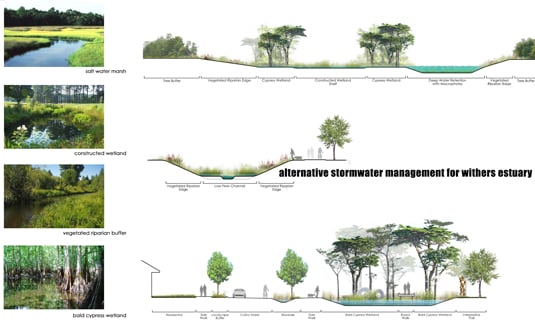

Image by Chambers Design

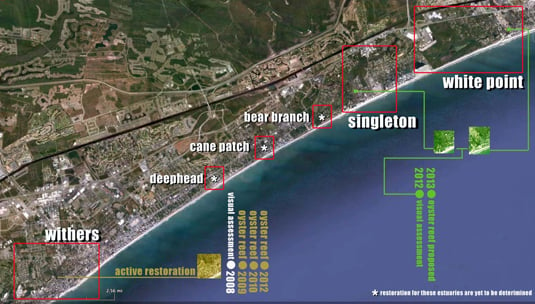

Since 2007, I’ve headed an oyster-tecture project in Myrtle Beach (located in northeastern South Carolina). It abuts Long Bay, which connects the city to the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The project started as a community collaborative focused on a single estuary known as Withers Swash, and is now growing to include additional estuaries with a vision of serving the entire northern coast of the state, which is comprised of Horry and Georgetown Counties. These two counties form the inner rim of Long Bay, measuring approximately 60 miles in length. It is known as the Grand Strand and is a major tourist destination for more than 10 million visitors each year.

In the last five years, our oyster-tecture venture has conducted water testing, annual oyster reef installations, visual assessments of four estuaries in the area, and initiated a shell-recycling program. We participated in the master planning for Myrtle Beach’s Withers Swash District Plan, partnered with local non-profits for bi-yearly cleanup days and pursued grants to continue to grow the program. Like many other oyster programs, ours depends on volunteers, donations, and partnerships that bring expertise in topics such as ecology, storm water, policy, urban design, and strategic long-term planning. The core of the team consists of Coastal Carolina University, the City of Myrtle Beach and my company, Chambers Design. Other team members include the Grand Strand USGBC branch, the local Surfrider Chapter, NOAA, local businesses such as Shield Waterproofing and KOA Campgrounds, and community members.

Image by Chambers Design

Start Small

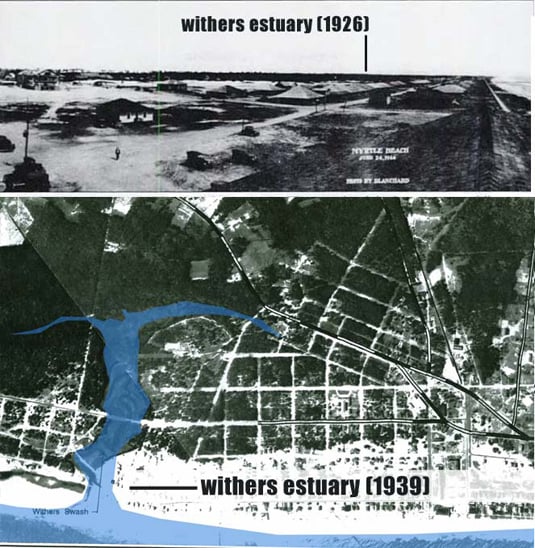

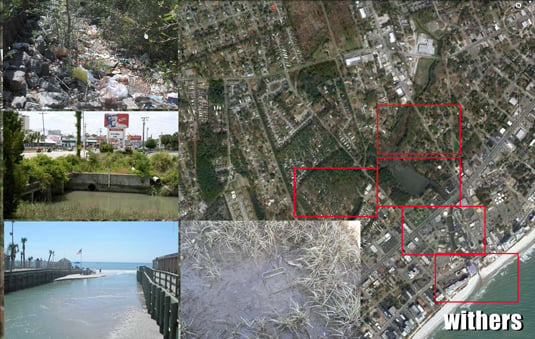

The initial goal was to deal with Withers Estuary’s water quality issues, stemming from pollution and storm water discharge. Withers is fairly minor – measuring only 4.2 square miles. However, at points throughout the year, high levels of fecal bacteria lead to closing the beach situated where Withers empties into Long Bay. This is not good for tourism, property owners or residents near the estuary.

Image by Chambers Design

Myrtle Beach has seen an incredible amount of construction over the last 50 years. Over 98% of what is the vacation hotspot today didn’t exist 3 to 4 decades ago. In the 1950’s, Withers was surrounded by forests, marshes, sand dunes, and wetlands. Today it is channelized and practically 100% of the natural groundcover has been replaced with hardscape such as buildings, parking lots, and roads. The impervious surfaces coupled with the change in the ecological fabric are the leading causes of worsening conditions at the beachfront and in water quality. We started the oyster-tecture project because historically oysters filled Withers. Reestablishing them would allow the city to reap the benefits of their filtration abilities. Oysters would help to ecologically restore the area and induce other species such as crab, herons, anadromous fish, and aquatic grasses into naturally repopulating reefs.

Image by Chambers Design

In the spring of 2008, we installed the first reef, and have continued to do so annually. Fed fully by volunteers, donations of shell, and love for nature the project has been able to reassemble about 250 square feet of oyster reef without any funding. Though nowhere near the amount needed, visual assessments show that the oyster population has more than doubled in Withers since the beginning of the project.

Image by Chambers Design

Starting small has allowed us to create a truly dedicated community collaborative and given us the time to investigate how our project can interconnect the needs of all stakeholders— from tourists to residents to the economy to biodiversity. It also allowed us to create a track record of success to show the community we are serious about providing the best for Myrtle Beach. The more the community sees our commitment manifest itself in reefs, the more volunteerism and growth we experience. We hope to secure our first grant this year to enact measures toward larger goals of positively enhancing the region.

The Bigger Picture

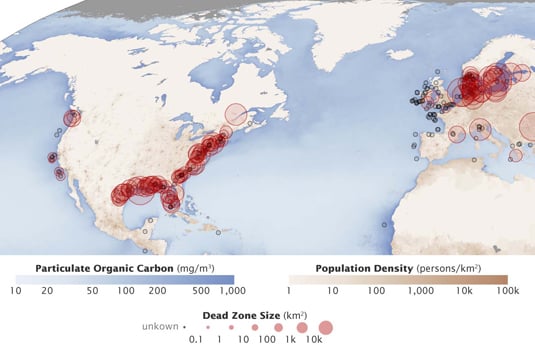

The Grand Strand has a wealth of estuarine habitats. Approximately 15 to 20 individual tidal creeks, bights, inlets, and tidal basins form a complex system of estuaries each fairly independent from the others. As the region grew, municipalities used these natural watersheds as drainage catchments for storm water runoff—similar to how Withers is used today. The outcome is wreaking havoc on the ecological health of Long Bay. Long Bay is one of several water bodies in the Atlantic Ocean with reported coastal hypoxia events–episodes of low dissolved oxygen concentrations that can significantly impact living organisms in the coastal ocean.

Image by NASA

Building off the accomplishments of Withers oyster-tecture project we now see that our efforts should be replicated in all of the estuarine habitats of the Grand Strand. In concert with the new 2012 Withers oyster reef installation, we visually assessed two additional estuaries for oyster reefs next year— White Point and Singleton Estuary. Compared to Withers, these two habitats are in much better shape, but still need assistance.

Image by Chambers Design

White Point is an expansive marshland sprouting into two directions and encompassing a wide variety of partially intact eco-zone. During the assessment, we found what marine biology experts would consider a healthy oyster reef coating the piers and belly of an overpass. We found indication of stingray, needle clam, and other aquatic life. At first, I thought the landscape was pristine because it was protected as a nature preserve, however no safeguards insure its survival. As we grow the oyster project into White Point, it will be necessary to find out if and how to protect it from future development.

Image by Chambers Design

The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) donates the shells used for Withers. This has been a pinch point for us. The majority of the SCDNR’s efforts are focused on the Lower Country of the state, which eats up an immense portion of the available shell. So we are working with a local recycling company to get shell from local restaurants, thereby eliminating a percentage of garbage currently going to landfills. The recycling program will provide access to 10 to 12 times more shell than we currently have. This will permit us to double or triple the size of the reefs going into Withers as well as grow into White Point, Singleton, and other estuaries as we assess and locate optimal sites throughout the Grand Strand region. Over time, we will restore oyster populations throughout the entire 60-plus miles of the Long Bay shoreline and hopefully reverse the negative effects caused by storm water runoff. With new oysters will come new populations of game fish, carbon sequestration, shore protection, and a living example of how a community-led group can affect urban design on the local level. The achievement in Long Bay could seed a revival of oysters in Winyah Bay (to the south) and along the southern tip of North Carolina (to the north), and get us one step closer to a metapopulation.

Image by Chambers Design

In terms of ecomimicry, we are creating a functioning water quality infrastructure at a fraction of the cost of alternatives like manmade filtration plants or other engineered solutions. Reintroducing oyster substrate in the form of shell is not the only activity needed to eliminate the water quality problem in Long Bay, but it is super step forward. We have worked with the City of Myrtle Beach to envision a city center that incorporates ecomimicry as a core design component.

Master Planning

In the summer of 2010, we contributed design ideas to the Withers Swash District Plan to revitalize the downtown area of Myrtle Beach. We worked with the project’s architects to explain, qualitatively and quantitavely, how a coastal urban area can develop while managing and increasing biodiversity. The master plan offered us a unique opportunity to meld conservation biology with city design and economic feasibility. Included in the concept are plans to de-channelize parts of Withers, enhance riparian strips, naturalize drainage pathways, integrate ecological standards for building design, and promote healthy lifestyles within the district. The city approved the plan as their long-term strategic roadmap for future development and it will be enacted in phases during the coming years.

Image by inFORM studio

Withers was the proving ground for the idea of oyster-tecture; it shows how small can grow into something much bigger. It takes a large amount of patience and expertise as well as teamwork, creativity, and the ability to communicate. Myrtle Beach can be a role model for how other coastal municipalities can effectively grow a regionally significant cooperative to address the pressures of growth and economic realities. Our oyster-tecture project is an excellent example of marrying science and design for targeted change. The goals can’t be one-sided for projects like this to work. We must consider all stakeholders from real estate developers to governmental officials to residents to business leaders and non-profits. Equal benefits must be realized for all species (including humans), as well as financial capital. Without a fully integrated strategy, the entire process can be jeopardized.

Neil Chambers, LEED-AP is the CEO and founder of Chambers Design, a research-based, contemporary design company, focused on next generation architectural and technological solutions based in DUMBO Brooklyn. He is the author of Urban Green: Architecture for the Future. Neil’s work includes urban design, green building design, energy assessment, master planning, and habitat restoration. He is interested in the relationship between ecosystems, ecological services, buildings and infrastructure. He has taught at NYU and FIT as well as spoken throughout the United States and around the world.

This post is part of the Re-imagining Infrastructure blog series.