January 30, 2014

A Pair of Artists Use Architecture to Study Film

‘Interiors’ is a journal dedicated to the study of film and architecture.

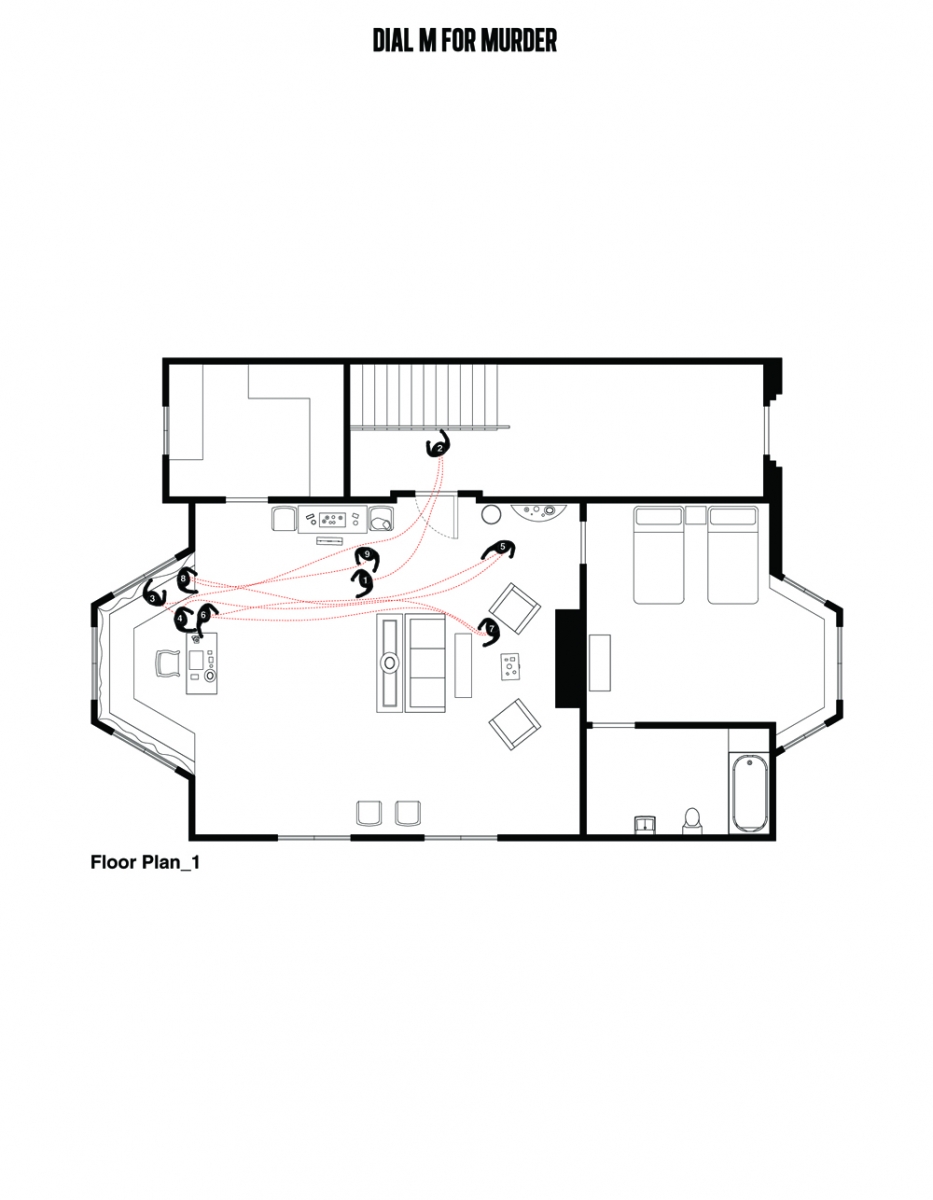

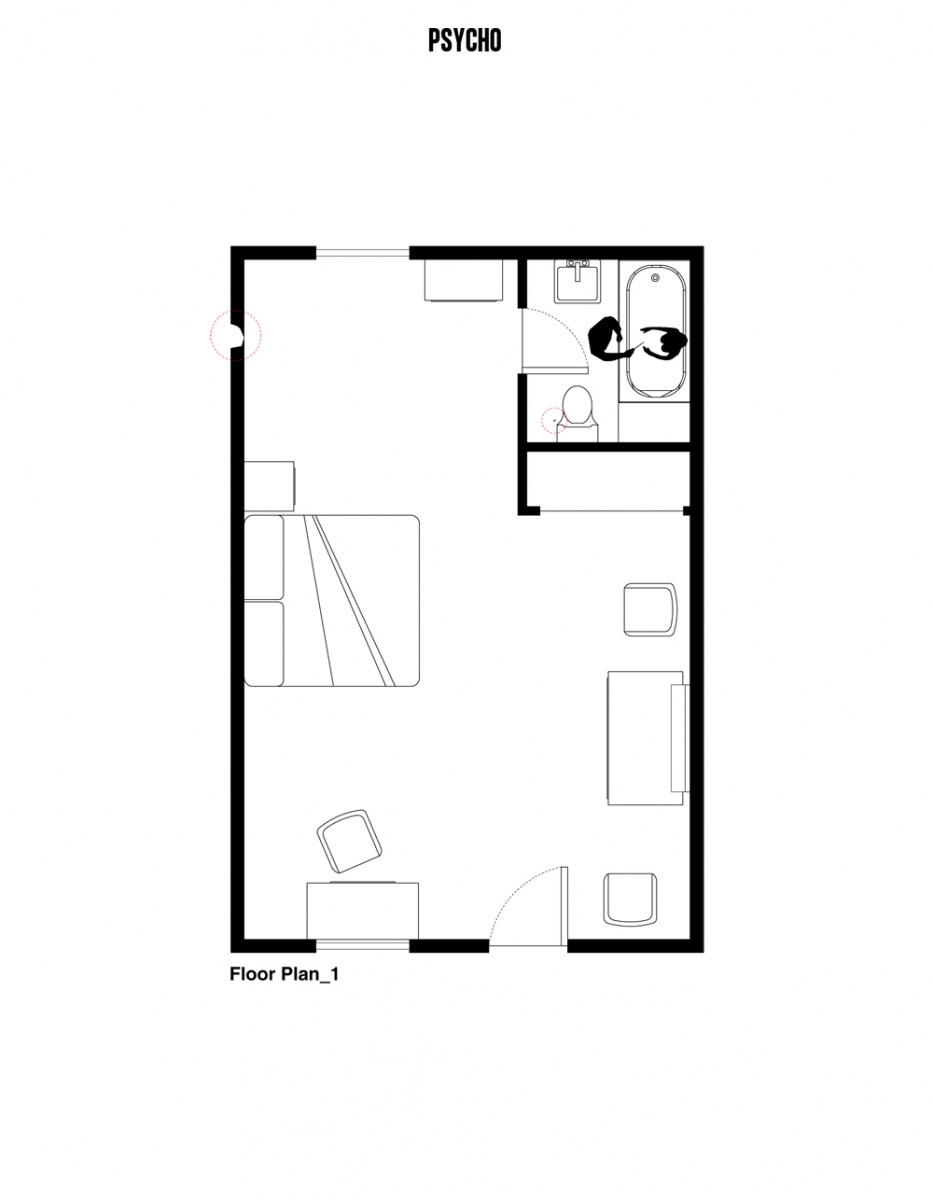

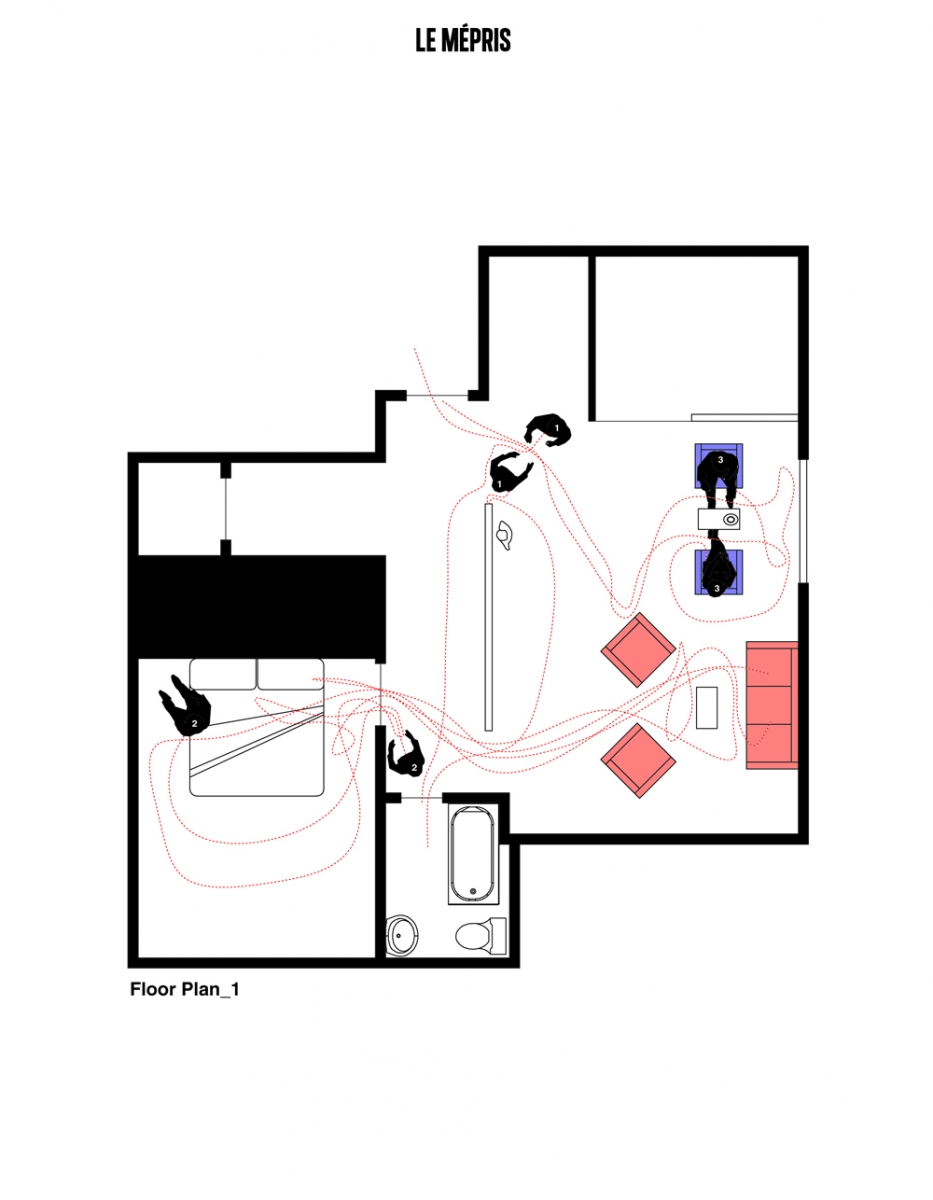

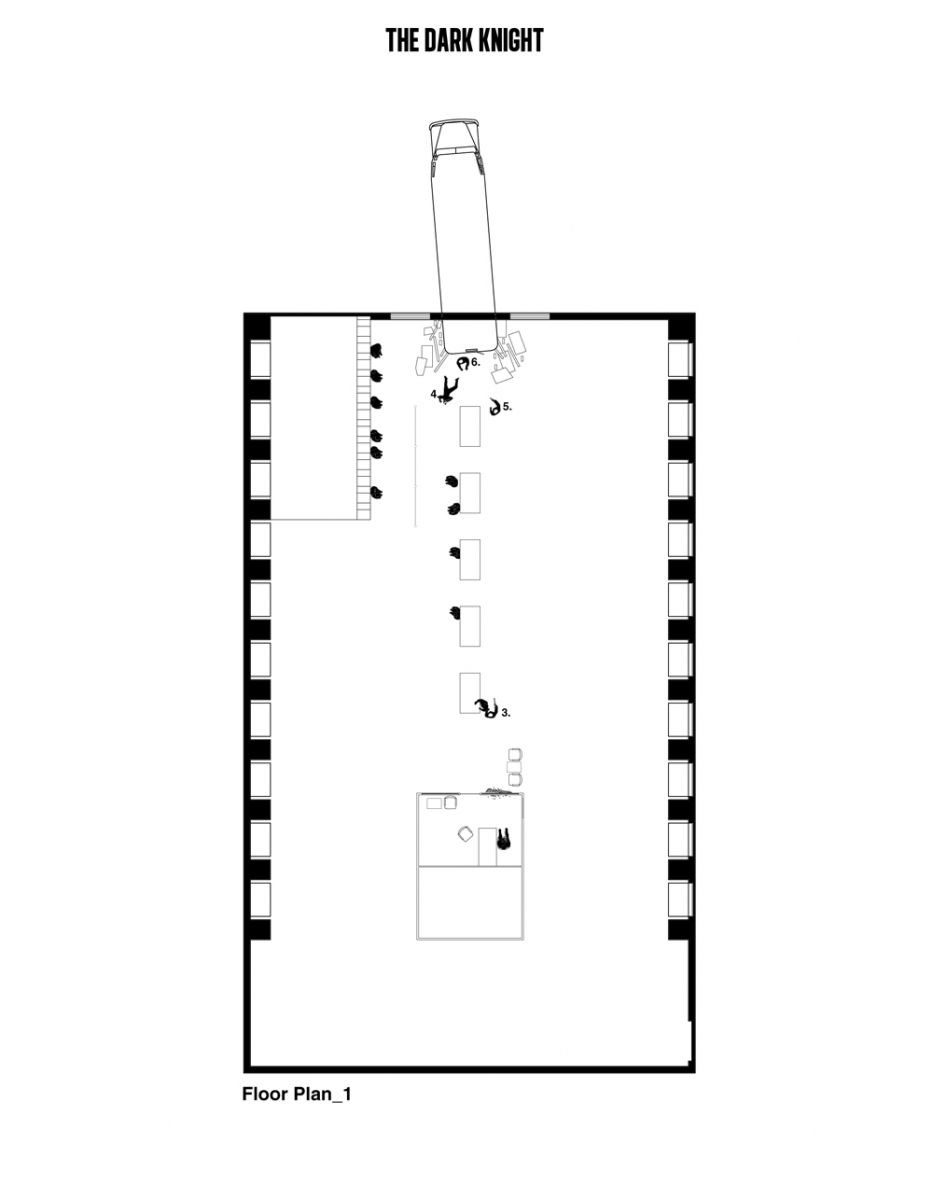

Can a good film director be a good architect? That’s the premise behind Interiors, a monthly online zine that critically investigates the link between film and architecture. Each issue breaks down, in architectural notation, a memorable set or scene from a movie or television series. (Lately, the subjects have expanded to include a Justin Timberlake music video and even a stage from Kanye West’s Yeezus tour.) The diagrams are accompanied by a lengthy essay that supplements the spatial analysis.

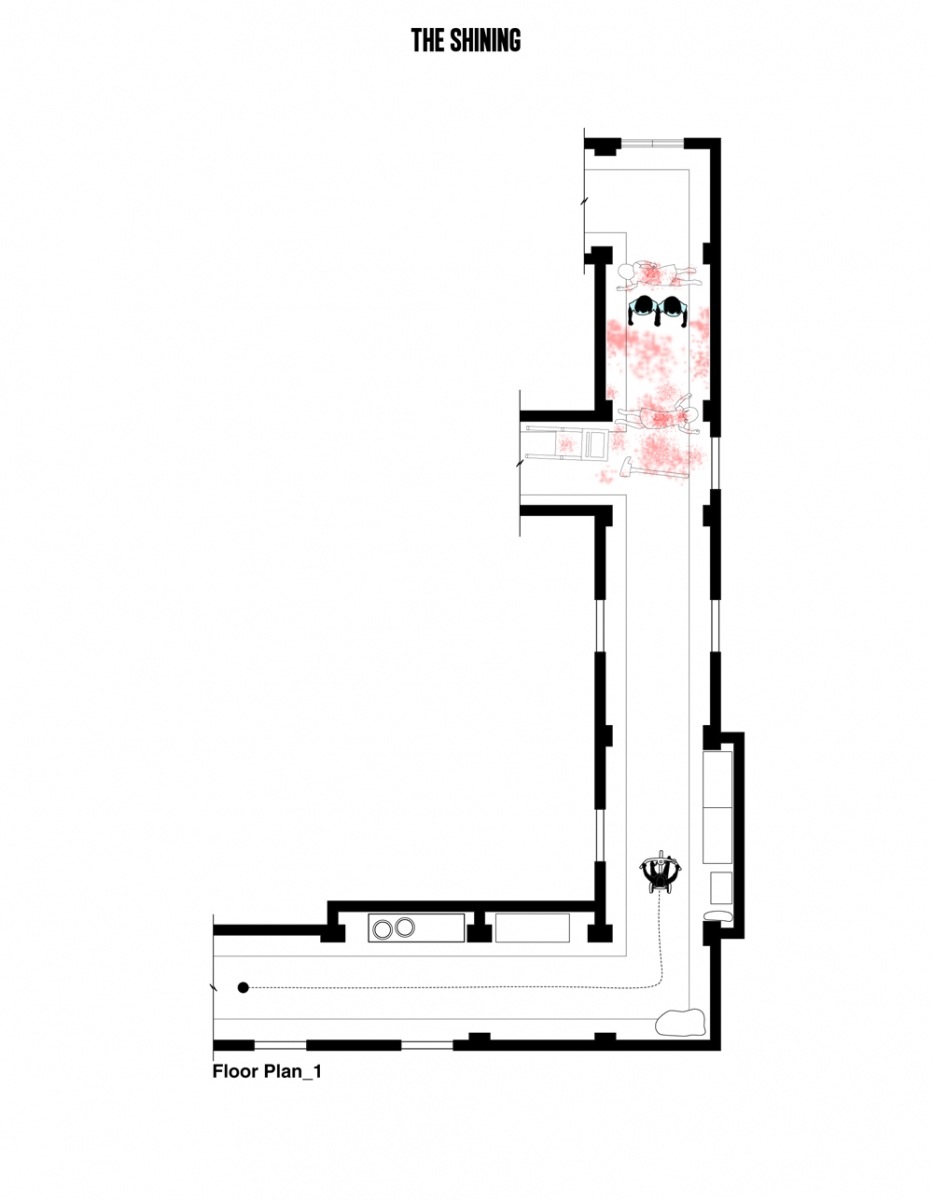

Films like Kubrick’s The Shining, Woody Allen ’s Annie Hall, and Disney’s animated feature Up have all been featured in the two years since co-founders, Mehruss Jon Ahi and Armen Karaoghlanian launched the series. At the time, the pair, who describe themselves as artists, had felt the study between architecture and film to be lacking. “We thought that we could start a new conversation.” Ahi says. “And Interiors became a space for that sort of conversation,” adds Karaoghlanian.

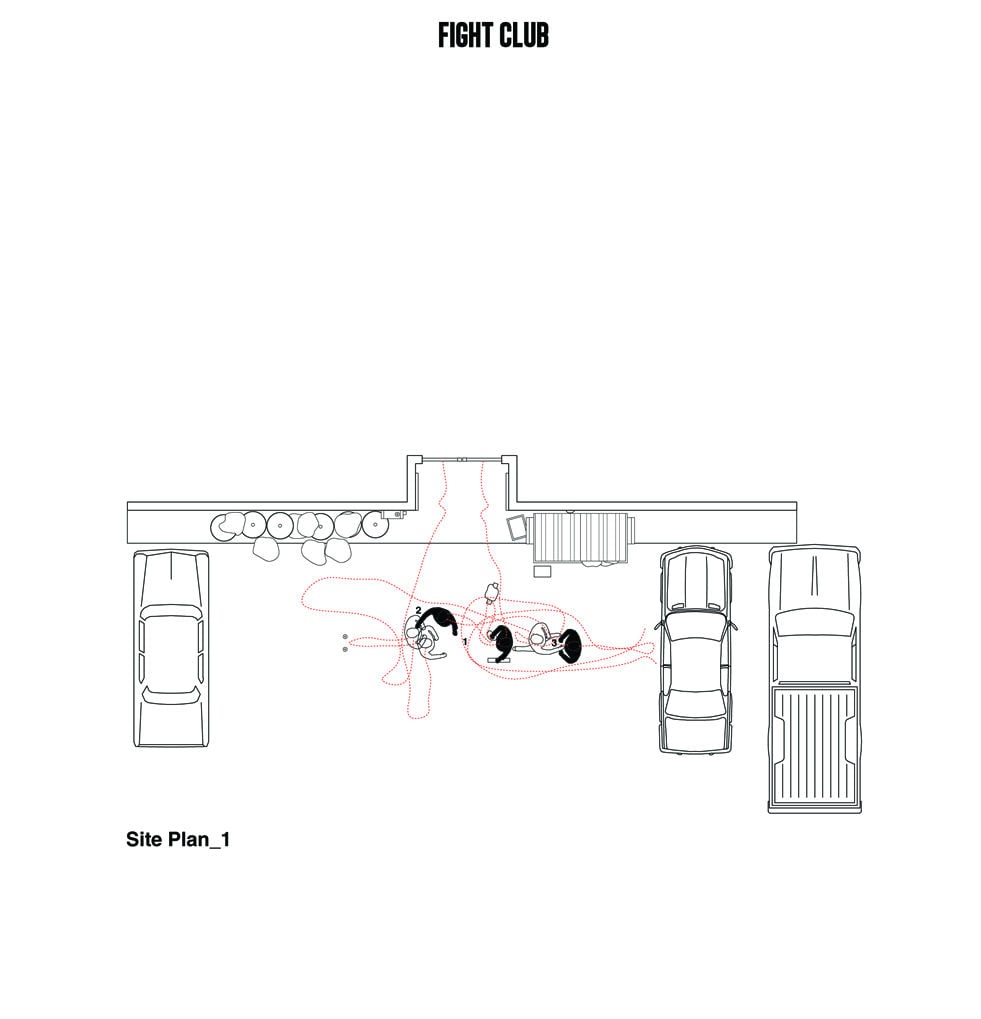

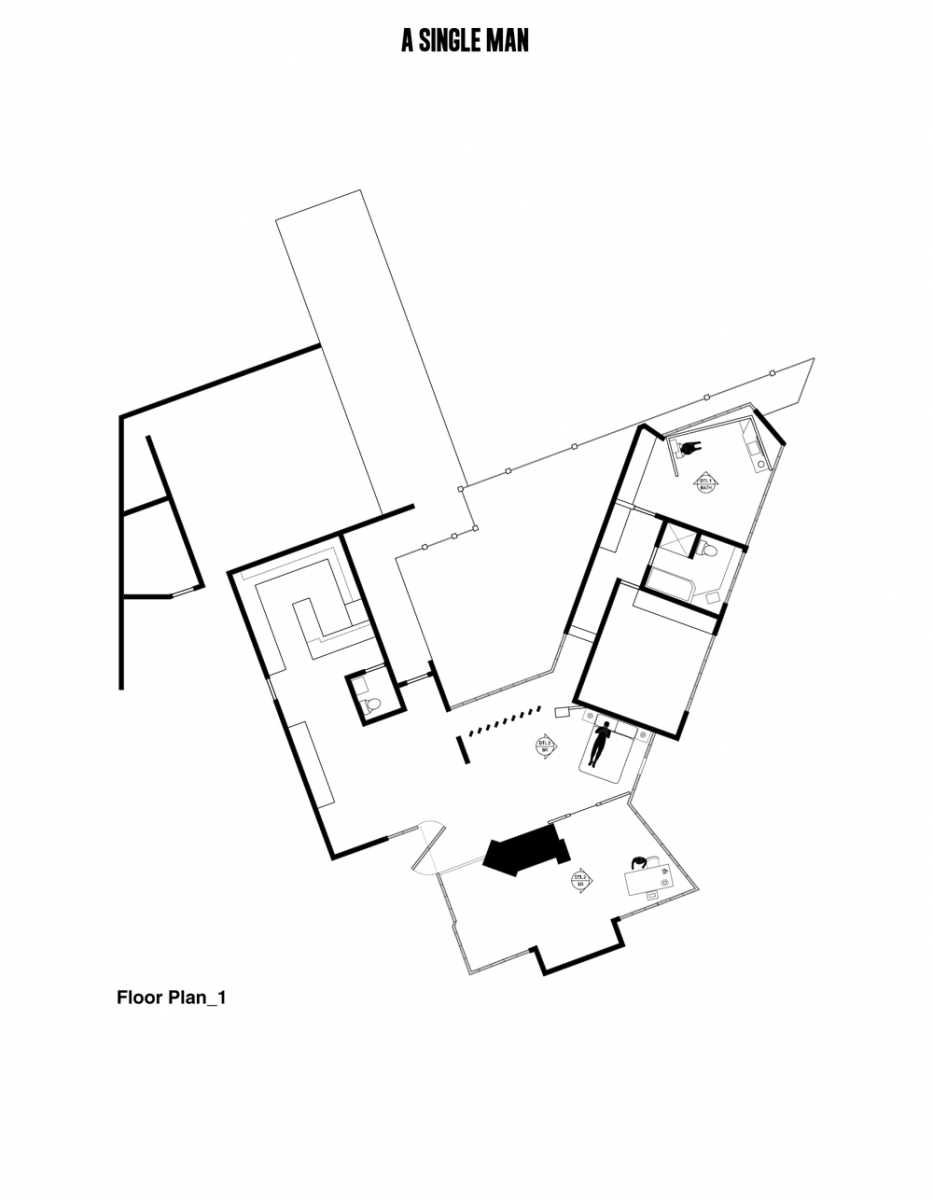

A diagram from Interiors latest depicts an important scene in David Fincher’s Fight Club, when Edward Norton and Brad Pitt’s characters duke it out in the parking lot.

But how do they go about choosing a film to analyze? First, the scene in question should be spatially compelling, a fact confirmed by watching the film and highlighting points of interest. Beyond its architectural verve, however, the scene must prove pivotal to the film’s structure and thematic narrative. Ahi and Karaoghlanian then consider whether the same set or scene has already been discussed elsewhere and in what depth it was studied.

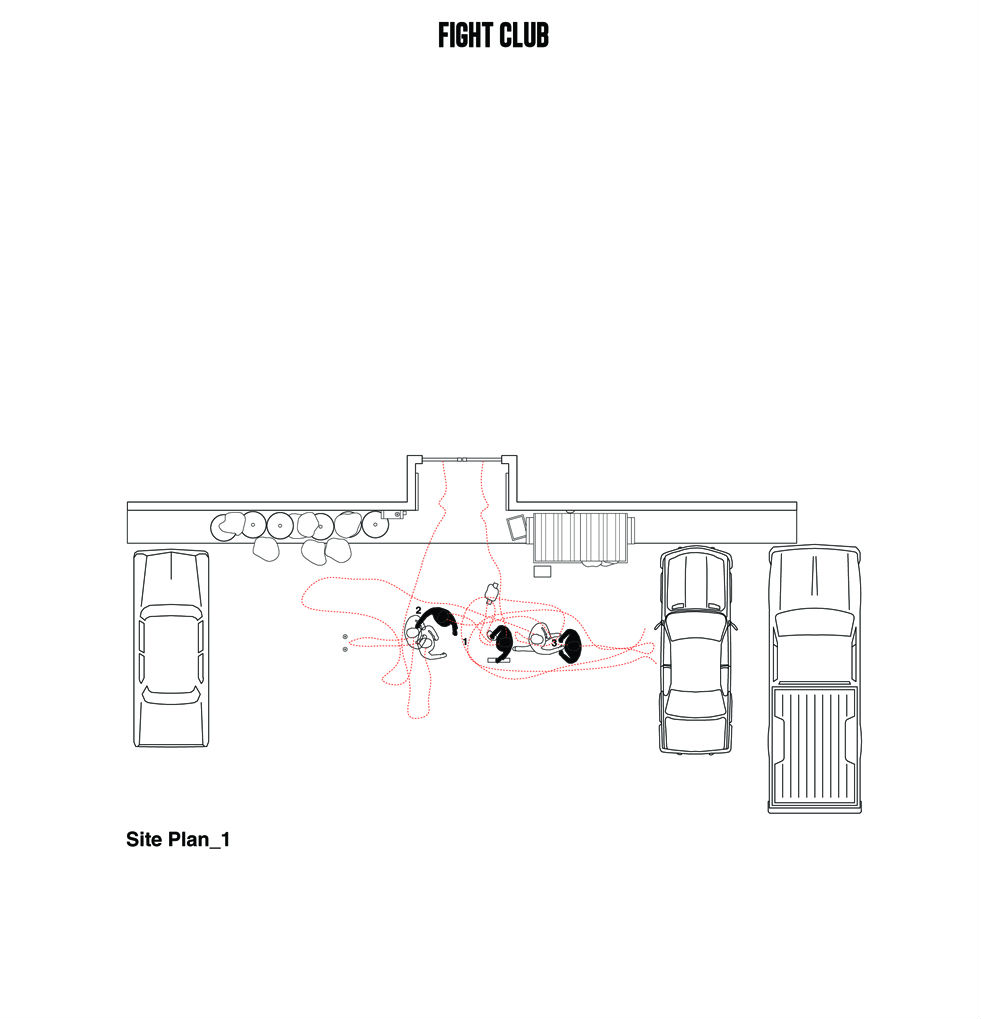

Easier said than done. Ahi and Karaughlanian spent weeks analyzing Interior’s first subject, David Fincher’s Panic Room, to determine if recreating a movie scene’s floor plan was even possible. Twenty-five issues later, the analytic process, though still tedious, has become a bit more streamlined. A film is watched scene-by-scene with notes taken on narrative and spatial cues. Individual scenes are often dissected frame-by-frame, each square inch poured over. Once the smallest spatial cues—a door’s placement or an actor’s exact height—are fully realized, the formal diagramming and writing process can begin. Says Ahi of the final product, “[while] it’s impossible for all of our diagrams to be 100% accurate, we strive to get it as close to that as possible.”

The criteria is extensive and the analysis methodical, qualities that can be easily applied to the filmmakers Ahi and Karaoghlanian most admire. “The two directors that I feel have a high understanding of architecture and space are Stanley Kubrick and David Fincher,” Ahi says. “What we’ve found is that when a director is able to look past the façade of architecture and actually incorporate the interior and exterior space within the themes of the narrative then it creates a much stronger piece.”

Issues can be viewed (for free) at Interiors website, while posters can be purchased directly through the journal’s store.

Panic Room, Issue 1

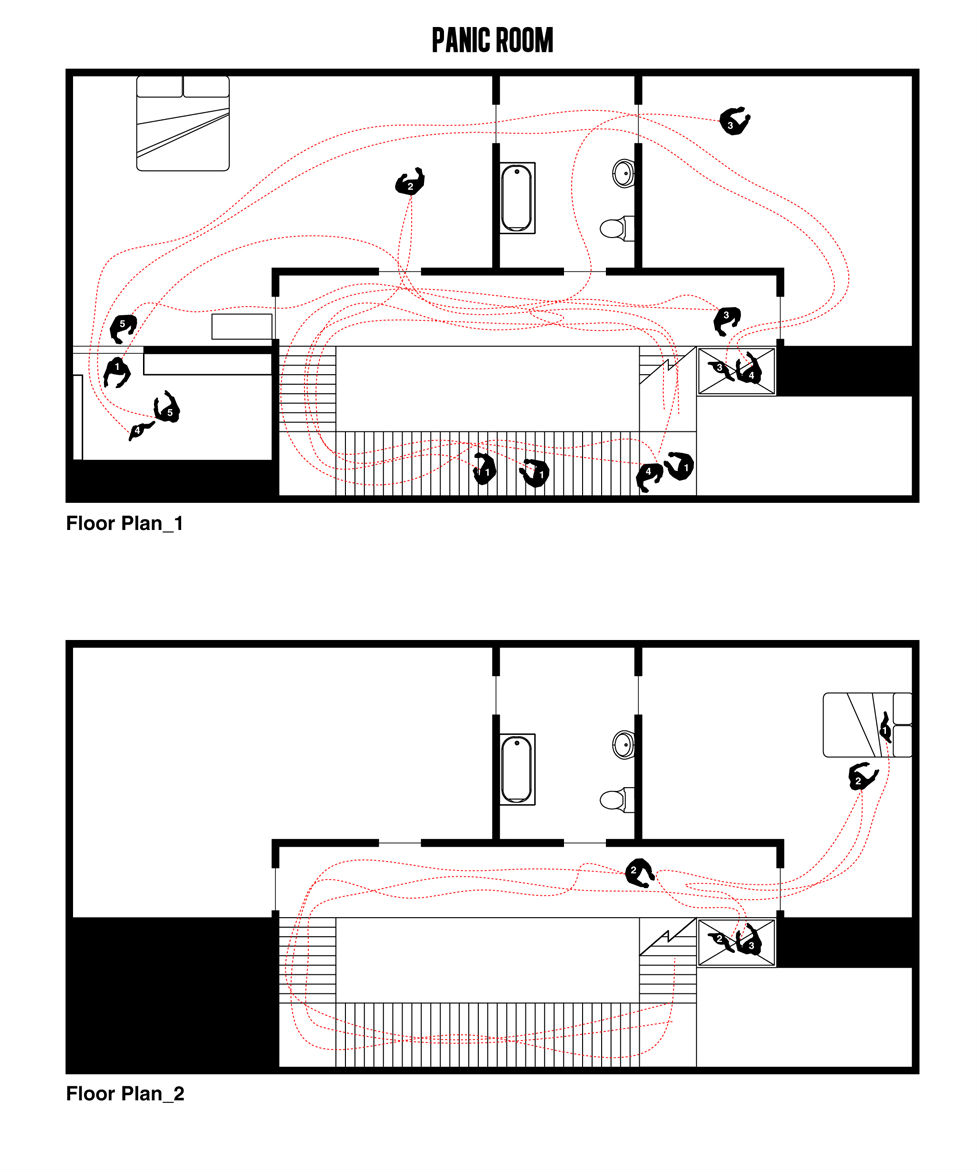

A Single Man, Issue 21. In the Tom Ford-directed film, John Lautner’s Schaffer Residence stands in for the lead protagonist’s home.

Dial M for Murder, Issue 22

Psych, Issue 10. Compare the floor of Room 1 of the Bates Motel with that found in Steven Jacobs’s book, The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock.

Le mépris (Contempt), Issue 2

The Dark Knight, Issue 7

The Shining, Issue 18

Up, Issue 15