August 28, 2013

After Hurricane Sandy: New York City’s Vulnerable Relationship to Water

New book points to New York City’s enormous water resources and lack of political will to tap it

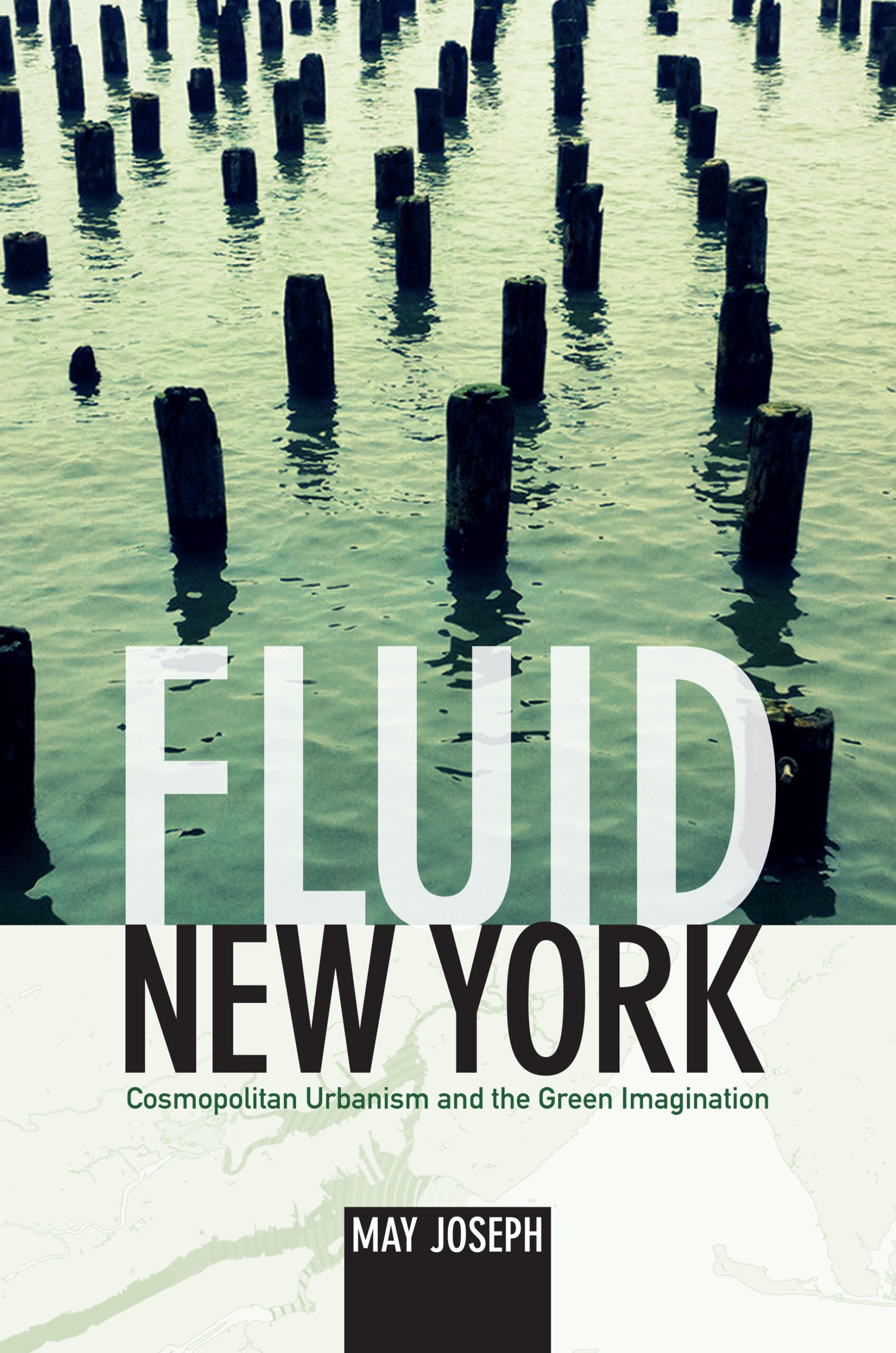

In our post-Sandy coverage, we devoted the February 2013 issue of Metropolis to the question: “Are we ready for the next one?”. Apparently we’re far from being ready, as a new book, by social scientist, May Joseph, argues. Hit personally and tragically by the ravages of the hurricane, this solid researcher, astute analyst, and smart storyteller presents her findings in Fluid New York: Cosmopolitan Urbanism and the Green Imagination. She puts our ecologically vulnerable city’s relationship to water into historic context, as well as in a world context of extreme weather patterns and how other places are dealing with the same problems that confront us.

Joseph sounds a hopeful note on the upcoming New York elections and the candidates’ engagement in connecting our archipelagic city with climate change. I wish that were so. The real issues looming over us, such the need to re-assess our relationship to water and rethink our infrastructure are rarely, if ever, mentioned in this season of political mud slinging. I suggest that every candidate, and every New Yorker of voting age, get a hold of Fluid New York. Start with the chapter, After Hurricane Sandy, excerpted here.–SSS

Water in New York has a special significance. An archipelagic city,

New York is surrounded by water, yet because of its density and skyline, people rarely get to see water lapping at the shores of their city. If you take a walk along the newly created greenways skirting the city today, you will see gentle waves splash the sides of the city, depending on the tide and the wake of the ships sailing by. Water is for New York a source of respite, a restorative, a precious commodity whose urban history involves a steady disappearance from its contemporary landscape. Coney Island became a focus of this fascination for the elusive element of water at the heart of metropolitan living.

On October 29, 2012, the city’s relationship to water changed irrevocably. A new dread has crept into New York’s unconscious. It is a historically unprecedented unease with what the sea portends for New York’s extensive waterfront communities. Water is no longer an innocent and leisurely commodity upon which the business of the city is transacted. It is now an ominous threat. Where the ocean used to beckon, at the Verrazano Narrows, at Far Rockaway, at Breezy Point, at Staten Island, at Sandy Hook, the shoreline evokes a scene of homes destroyed, a way of life washed away unexpectedly.

What is shocking about this scenario is not the fact that a storm of unimaginable magnitude wreaked so much devastation along New York City’s waterfront, though the fury and enormity of the storm was unprecedented its scale and force. The shock comes from the extent to which New York has been unprepared for its ecological context as an archipelagic metropolis by the sea.

Storm Surge City

New York is a city vulnerable to storm surges. Climatologists have been warning for years that storms of considerable magnitude are inevitable for the city. Out of 140 port cities in the world, New York stands fifth for risk of flooding from storm surges. Tropical Storm Irene demonstrated, in August 2011, New York’s precariousness, when it stranded without electricity half a million consumers in the region. Much of the city’s transit networks, such as its subway system, as well as its water tunnels and electrical conduits, lie fifteen stories below sea level. Planning infrastructure to prevent catastrophe is expensive, but cost effective in the long term, if the city is going to survive the reality of rising oceans.

The cataclysmic Asian tsunami of 2004 and the subsequent tsunamis in

2009 and 2011 did lead to public discussions in New York City addressing disaster preparedness in the eventuality of a major oceanic disturbance. Yet, New York has done little in the way of actual storm surge management to prepare for the unthinkable scenario of sinking waterfronts and the extensive flooding of vast areas of the city’s enormous coastline. Official public discussion about climate change in New York has largely centered around evacuation planning and disaster management, rather than disaster prevention, something other water-bound cities around the world have been implementing for at least thirty years. For instance, Singapore has developed a giant marina comprising a system of nine crest gates operated by giant pumps to improve drainage infrastructure and contain flood plains. Rotterdam has built a complex of seawalls, barriers, and dams designed to redirect storm surge waters to the advantage of the city. The Rotterdam model’s innovation lies in its aim to convert a potentially destructive influx of storm water into usable water. Rotterdam’s preparation to prevent storm surges includes a water plaza for leisure, a water-storage facility, a floodable terrace, and waterproof commercial spaces. And London has strategically constructed ten giant surge barriers along the River Thames to dissipate the force of a surge.

New York, in comparison, is inexcusably behind the times when it comes to being prepared for climate change. For a city of its scale and import, it has little to offer the world, regarding how cities can improve their infrastructure. Instead, New York is an example of environmental hubris. After the superstorm, the city became emblematic of the sort of thinking that leads to the devastation wrought by climatic extremes. This thinking, that Hurricane Sandy was a once-in-a-lifetime storm, that this kind of oceanic disturbance is an anomaly that won’t happen here again, is the sort of planning error that will allow future water-related disasters in New York. Leaving infrastructural change to the vagaries of politicians preoccupied with how much mileage investing in expensive infrastructural building will bring them in the next elections is a dangerous path for New York.

So far, adaptation in New York to climate change has been relegated largely to cosmetic government initiatives such as bike lanes, transportation redesign, expensive architectural makeovers, and city-beautification gestures in the public sector. The city’s future has not yet been viewed as an inescapable, shared fate requiring large-scale, expensive engineering redesign for storm surge protection. Instead, the conversations in the aftermath of Sandy suggest that communities and regions affected by the storm are being asked to independently deal with the environmental catastrophe as a private, personal tragedy. This approach permeates many spheres of everyday life following the hurricane.

The most obvious example of the blurred lines of post-Sandy accountability was the dramatic visual impact of the electrical blackout across downtown Manhattan, from Thirty-ninth Street southward. One resident of Greenwich Village described walking south from the well-lit mid-Manhattan area toward an eerily dark Greenwich Village below Fourteenth Street as an apocalyptic journey. This cloak of darkness, the result of the collapse of New York City’s electrical grid, exposed the city’s inadequate electrical infrastructure, which had been flooded by the storm surge. In contrast, the Netherlands has invested in a storm-proof power grid, installed underground and using water-resistant pipes. Their power lines are designed to withstand the extremes of wind and rain.

Planning for Sandy ought to have included generators for every high-rise. Instead, negligence in Albany, City Hall, and at the neighborhood level left a vertical city in crisis. Large populations of people on high floors were stranded without elevators or safety lights in their emergency stairwells. The shocking case of the Sand Castle, four gargantuan tower complexes in Far Rockaway, Queens, staged the extreme horrors of poor disaster preparation and the privatization of storm surge planning. Left without electricity, water, assistance of any kind, and cut off from the outside world because of power failure, the high-rise complex became a deplorable example of the dangers of vertical living. Astonishingly, very few high-rises in New York City have thought it necessary to bolster their emergency planning with the minimum of backup generators to run at least one elevator per building.

Mold in dry walls and the crevices of flooded homes also came to be treated as a personal issue, rather than a public health matter related to the storm surge. One of the consequences of flooding by seawater, seeped sewage, and the contamination of neighborhoods by untreated sewage is the problem of mold. Mold singularly contributed to the large-scale damage of household property, clothing, furniture, home infrastructure, and basement structures during Sandy. The spread of mold is swift and hard to clean up. Its toll on public health is deleterious. Moldy furniture has to be destroyed.

In the wake of Sandy, the extent to which individuals and communities were able to clean their homes of mold became a question of economics.

The more educated and affluent the community, the quicker the blight of mold was attended to. For underserved communities, the danger of mold considerably deteriorated their quality of life. Many affected neighborhoods did not have early access to information or assistance to cope with the post-hurricane clean up. Families were temporarily displaced from residences deemed uninhabitable by city officials. After a major flood, the eradication of mold to avoid environmental biohazards is the sort of public health issue, among many, that cities like New York must prepare for. Educating residents of coastal cities in public health concerns related to storm surges should be part of the larger plan for storm surge preparation.

The problem of mold is just one among many impending planning issues that Hurricane Sandy raised in the first few weeks following the storm. The panic around gasoline and transportation networks was another major point of anxiety and breakdown. Reports suggest that panic around the perceived lack of fuel led to the extreme shortage of gas in the New York City region, further exacerbating an already stressful existence with additional hours of commute and lines of waiting to get a rationed amount of gas. The shortage of gas led to a lack of food and services requiring gas to keep them running. The resulting paralysis of poorly stocked grocery stores, disrupted transit, fragmentary social services, and intermittent cab services generated a slowing down of economic activity in the city.

The converging issues of electrical outage, mold, and gasoline shortage during the storm surge are instructive of the multiple secondary issues that accompany urban water disasters. They make up what in disaster management are termed “lifeline systems.” These communicative infrastructures integrate transit, power, and communications after a catastrophe. Hurricane Sandy brought to light the extent of unpreparedness on the part of both the state and city governments in New York, despite warnings about the scale of the storm.

Water as “Blue Gold”

Much of the conversation regarding storm surges in New York assumes that water is a problem. The assumption is that the right set of solutions, such as a storm barrier, will dissipate the problem. But this is where New York can find inspiration across the Atlantic, in the maritime town of

Rotterdam, Holland. In 1953, a catastrophic storm surge forced the city to start constructing barriers, seawalls, and dams. The national undertaking, titled Delta Works, was recently revamped with a rethinking of water as an opportunity, rather than a problem. Arnoud Molenaar, the head of the Rotterdam Climate Proof Program, states that the group took the approach that water from the sky and ocean could be converted into “blue gold.” According to Molenaar, the conventional emphasis to block water from gushing in, or the reactive approach taken by New York City to evacuate people out of the path of the deluge, is to miss the challenge presented by the situation: how can excess water be productively harnessed for storm surge management.

Molenaar’s thinking on storm surge management is of immense import for New York City. The city will have to figure out ways to break the path of destructive surges and disperse the approaching fury of the ocean in the coming years. This scenario has already been presented by NYS 2100, the commission formed by Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to review and propose changes to the state’s infrastructure, to prepare for further extreme weather.

Landscapes of Adaptation

Seawalls, enormous harbor-spanning surge barriers with movable gates, the reclamation of oyster beds, and building dunes, wetlands, and oyster reefs are only some of the broad array of plans being proposed by city and state officials since Hurricane Sandy. Cultivating natural defenses as well as investing in hard infrastructure is the strategy invoked for the changing landscape of New York’s waterscape. A long list of infrastructural updating, including modernizing the city’s sewer system, protecting the subway networks, and strengthening utility services to avoid long blackouts, is being made, despite the skepticism as to where the money will come from to pay for this restructuring. A new mayor will be elected in 2013, and climate change preparedness is emerging as a critical topic in all discussions relating to New York.

But the city has very little time before the next storm surge hits, perhaps in a few years. After receiving the reports of the four commissions he charged to study the various aspects of Hurricane Sandy, Governor Cuomo emphasized in his state of the state address of 2013 that “there is a 100 year flood every two years now.” By explicitly locating New York City as an island city with a specific ecology of manmade environments that are vulnerable to rising sea levels, the governor has officially introduced climate change as a major part of New York’s future planning initiatives. Hardening the infrastructure of New York’s airports, transit networks, communication networks, and electrical, gas, and utilities networks are only some of the vast areas of restructuring the governor has brought to the official discourse of New York’s future planning.

However, all these proposals remain just proposals, unless the political will in Albany and Washington shifts from rhetoric to implementing policy, before the next catastrophe hits America’s financial heart.

Surviving Sandy

As a resident of the West Village who lives close to the Hudson River, I was devastated by Hurricane Sandy. During the Sandy blackout, my husband lost his footing in the pitch-black emergency stairwell of our high-rise. He suffered a severe traumatic brain injury and fell into a coma of many weeks. Our life tragically came apart, as we struggled alongside thousands of other New Yorkers seeking medical help at a time when some of the city’s major hospitals located downtown were shut down due to flooding. Critically ill patients were treated publicly, in open thoroughfares, corridors, and hospital lobbies in uptown Manhattan, their beds shabbily separated by makeshift cloth-barriers. New York seemed more Third World than I had ever imagined. The city appeared to be in triage, unlike anything I had seen before. It stunned me to realize that our well-heeled building of twenty floors, with fancy carpets and a well-designed roof garden, did not own a generator to keep at least one elevator active after the first few hours of emergency lighting. Such an obvious oversight was incomprehensible, as I had somehow assumed that every large building had its own backup generator, as is the case in many Indian high-rises. New York’s utter provincialism in emergency planning seemed incongruent with its precarious location as a coastal city in the path of major storm surges.

What surfaced during this terrible journey from personal devastation to recovery was the extraordinary social cohesiveness of friends and strangers from across New York who spontaneously stepped into my daughter’s and my lives, offering solace in the desolate underworld of disaster. Neighbors and friends opened up their doors and hearts, offered to walk my dog, care for my child, shop for my groceries, as I spent long hours in the intensive care unit, week after week during Sandy’s aftermath, well into Thanksgiving and Christmas. The sushi chef whose home in Queens had no water or electricity for weeks wanted to visit my husband in the hospital. The Chinese laundry staff asked about our welfare, despite the extensive hardship they were going through, without water, heat, or power for weeks in their homes, a two-hour commute away in Long Island. The celebrity butcher from Staten Island cheerfully ordered me to kick my husband back into consciousness. The extraordinary generosity of my neighbors, who cleaned my apartment, took care of my child, and left food at my door for weeks, took me by surprise, as we crawled our way through grief and shock. My bike shop mechanic made it a point to offer words of comfort in passing, amid despairing days. The Korean deli manager started giving me deals on my spring water. People rallied in unexpected ways, reminding me that my story was only one in the myriad tales of desolation and loss the city was going through.

This convivial urban sociality of formal and informal intimacies, which makes cities livable, opened up a layer of New York that is the reason many choose to brave the terrible storms that lie ahead. This intimate New York played out across the five boroughs, from the Far Rockaways and Breezy Point to Staten Island and Brooklyn. It is a New York of admirable social engagement and resilience, where people continue to look out for each other amid the city’s adversities, of which there have been too many in New York’s recent history.

May Joseph is professor of social sciences at the Pratt Institute, where she teaches global studies, and visual culture. She is also the author of Nomadic Identities: The Performance of Citizenship. This except, taken from Fluid New York: Cosmopolitan Urbanism and Green Imagination,Copyright Duke University Press, 2013.