May 20, 2013

The Enduring Impact of Edo-Era Japanese Prints

The influence of Japanese prints from the Edo era is still felt in art and design today.

EXHIBITION

Edo Pop:

The Graphic Impact

of Japanese Prints

Through June 9

Japan Society

New York City

AIKO, Sunrise, 2013

courtesy Richard Goodbody

The pristine walls of the Japan Society’s landmark building in New York City are covered in graffiti. The tattooed back of a scantily clad woman amidst a sea of waves, blossoms, and bunnies is a sign that the Brooklyn-based Japanese graffiti artist AIKO (Lady Love) has been up to her old tricks. “I let her do whatever she wanted in this space, and she spread her amazing, energetic, colorful composition everywhere,” says gallery director Miwako Tezuka, gesturing to the atrium entrance of Edo Pop: The Graphic Impact of Japanese Prints.

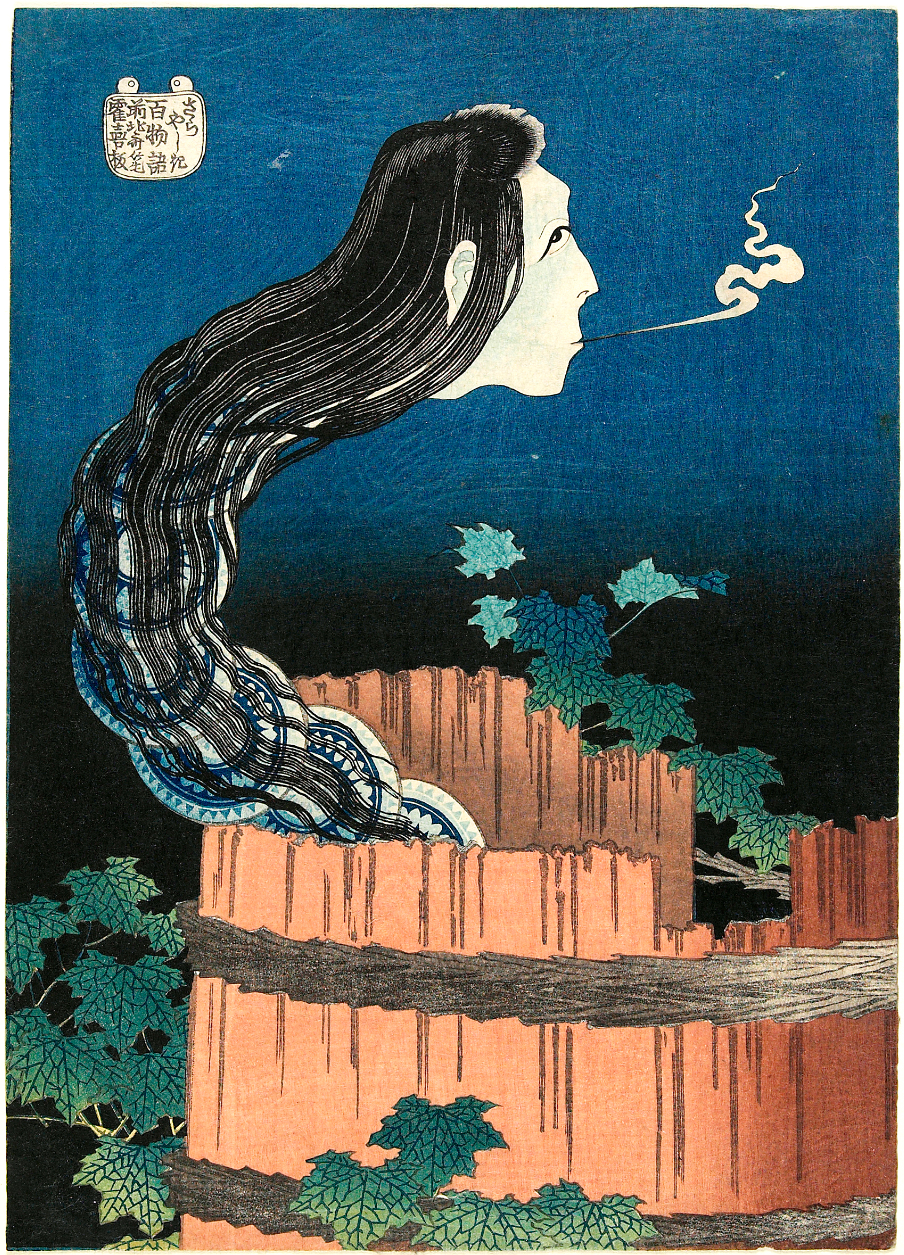

Katsushika Hokusai, The Manor’s Dishes, 1831-32

courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Arts

A former assistant for Takashi Murakami with her own burgeoning star status, AIKO intertwines Western sensibilities with street art and the traditional Japanese aesthetic in which she was trained. Thus, Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa laps at a figure that is itself a riff on an image of Tokyo tattoo culture by the photojournalist Martha Cooper. “She started to realize that there are a lot of affinities between today’s street culture and the popular culture of the Edo period,” Tezuka explains, referring to Japan’s early modern era of 1615-1868. “If she had been born in the Edo period, she would have been hanging out with Hokusai.” AIKO’s work is a testament to the notion that artists across generations and continents can speak to each other. “The mural really sets the tone for the exhibition,” beams Tezuka.

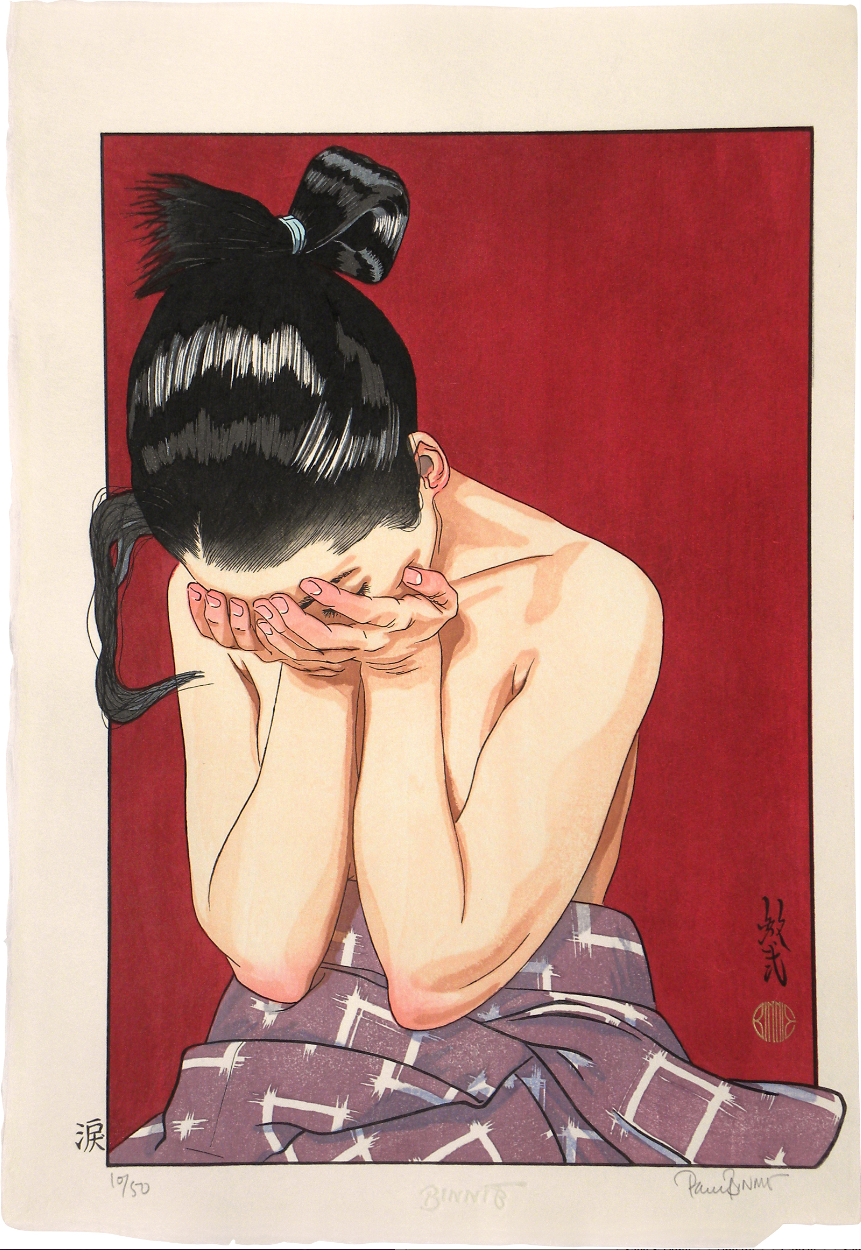

Paul Binnie, Tears (Namida), 2009

courtesy Scholten Japanese Art, New York

Tezuka’s satisfaction is well earned: Edo Pop, her directorial debut for the Japan Society, reveals the deftness and dynamism of both the art and its curator. Although originally conceived at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the graphic and graffitied glory of New York City’s Edo Pop—spawned from the same source material—is largely a product of Tezuka’s vision. Here, around 90 traditional ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) prints from the original exhibition are interspersed with 33 works by ten contemporary artists.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Shono–Driving Rain, ca. 1833

courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Arts

The result manages to exalt the courageous compositions and graphic force of ukiyo-e, while emphasizing its timeless quality. The images of courtesans, Kabuki actors, and samurai reflect the decadent entertainments and popular tastes of the emergent moneyed class in Japan’s early modern era. These are the posters of yesterday’s pop stars and postcard views of vacations past.

The modern artists in the show, too, have great staying power. The Japanese pro-snowboarder-turned-turned fine artist, Tomokazu Matsuyama, splices together manga, fashion, and ukiyo-e into luscious labor-intensive compositions. Sachiko Kazama’s massive woodblock print Alas! Heisoku-kan, one of a three-part series made following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, brings Hokusai’s Great Wave crashing into the twenty-first century with tsunamic force. Yesterday’s pop culture is invigorated with a powerfully modern current.

Katsushika Hokusai, Leading-A-Horse Money, 1822

courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Arts

While AIKO’s initial pop seems to fizzle into galleries of softly lit prints, it is in its subtleties and subtexts that Edo Pop’s seismic impact is felt across time. Fittingly, the word ukiyo, taken from Asai Ryoi’s 1661 novel Ukiyo Monogatari, embodies a life immersed in pleasure amidst a world of constant transience. Balancing timeliness and timelessness, Edo Pop is ultimately a reminder that the more things change, the more they stay the same.