May 5, 2022

Exploring the Weird, Wonderful Skyline of Art at Coachella

Each year the content is seemingly more futuristic and more surreal.

Paul Clemente

This year the show reprised some of its most popular past installations, including Robert Bose’s Balloon Chain, a wandering piece made up of hundreds of balloons extending hundreds of feet into the sky (this year’s version was blue and yellow, in honor of the citizens of Ukraine), and NEWSUBSTANCE’s Spectra, a spiraling, colorful 7-story tower affording views over the sprawling grounds. But because of COVID, the handful of new artists presenting work had to wait two years for their ideas to to become part of the show. (The 2020 event was cancelled just days before its scheduled launch that April.) For most projects, Coachella’s in-house design and fabrication team had to tear down what they had been building and start over, explains Clemente.

Looking out at the sea of installations, the first piece one got a glimpse of—a sort of gateway to the festival’s art zone and main stage—was Cristopher Cichocki’s 5-story-tall Circular Dimensions X Microscape, a white, bandshell-shaped structure inset with three circular tunnels, all constructed out of more than 25,000 feet of PVC tubes. Thanks to its hollow structural members, the installation seemed to disappear like a misty cloud when you saw it from the right angle at the right time of day—a visual sleight of hand that definitely impacted some concertgoers more than others. In the pavilion’s “nucleus” sat what Cichocki calls a “laboratory,” where scientists and artists together generated blobby and fractal-like “video paintings” on the walls by manipulating water, salt, barnacles, and algae from the nearby Salton Sea under microscopes. In this sense, Cichocki, based in the Coachella Valley, created the most locally-inspired piece of this year’s show—reflecting the valley’s strange, resilient ecologies and equally resilient infrastructures.

“We start to see things from both a very molecular level to a planetary level,” notes Cichocki. “Tiny creatures, bacteria, blood cells, and planets orbiting the solar system—all are connected. It’s the alchemy of life.” The piece’s visual projections were paired with an ever-evolving soundscape of field recordings and industrial rhythms that resonated through the tunnels and beyond. Cichocki himself DJ’d the music for stretches that lasted more than 7 hours at a time.

Just next door, Buenos Aires-based artist Martín Huberman created Cocoon (BKF + H300), a 9-story sculpture created from interlacing (and then welding) 300 reproductions of the iconic BKF, or “Butterfly” Chair and suspending them atop tall steel columns. The bent metal and slumped fabric or leather chair, originally created in the midcentury by noted Argentine architects Antonio Bonet, Juan Kurchan and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy, made its way into popular culture mainly through California-made knockoffs. And so the sculpture—with its silky white fabric “skin” of window shade material—is a nod to the region that served as a sort of cocoon to the chair’s mythology, all while burying the true story of its inception.

“It’s a tragic story, being erased from a moment,” notes Huberman. “So much of the culture is told through the American and European lens. Can you imagine erasing the Eames?”

At night the billowing piece, with its riot of lacy metallic edges, glowed in bright, supernatural colors inspired by the mysterious spaceship in the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind. It was a glowing, strange totem effectively reflecting a place that never feels quite real.

Not far from Cocoon stood the festival’s most monumental installation: The Playground, designed by New York-based Architensions, who laid out a multipart structure merging art, architecture and urban design. Its modular grid framework encompassed four thin, square towers, each ranging from 42 to 56 feet high, linked in places with sky bridges. In the hot sun the interconnected creations started to resemble the warping, soft-hued architectures of video games like Monument Valley. Each tower exhibited a variety of basic geometric forms—arches, circles, niches, squares— and was skinned with cyan, magenta and yellow dichroic films that bathed the surrounding area in colors. Other parts were mirrored to encourage interaction. And interact they did: Coachella-goers walked on raised platforms, hung from steel frames, and wandered around the installation’s 174-foot by 104-foot public square, where benches and nooks provided a welcome respite, and extremely popular selfie stations.

“We wanted to bring a fragment of the city into the festival, and into the area” says Architensions principal Alessandro Orsini, whose team was inspired to react to the decidedly un-urban sprawl of the Coachella Valley. “Yes, it was photographable, but we wanted people to experience it as a series of spatial moments; to enjoy the place, not just the pictures.”

Of course many of these subtleties were lost on the thousands of concertgoers, who generally didn’t make the long trip out to Indio just to deconstruct art, even if it was conveying radical messages or celebrating inspired self-expression. But that, too, was the point. “They create this kind of peripheral experience,” says Clemente. “Even if you’re not examining them or staring at them you feel them when you’re moving around out there.”

“The art is a sort of performance within the performance,” adds Orsini. “And the visitors perform on it and in it.”

“It becomes a kind of landmark,” adds Orsini’s co-principal, Nick Roseboro, of his team’s piece. Roseboro is also a trumpeter, and has performed at the festival in the past. “We kept hearing people say ‘meet us at The Playground.'”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

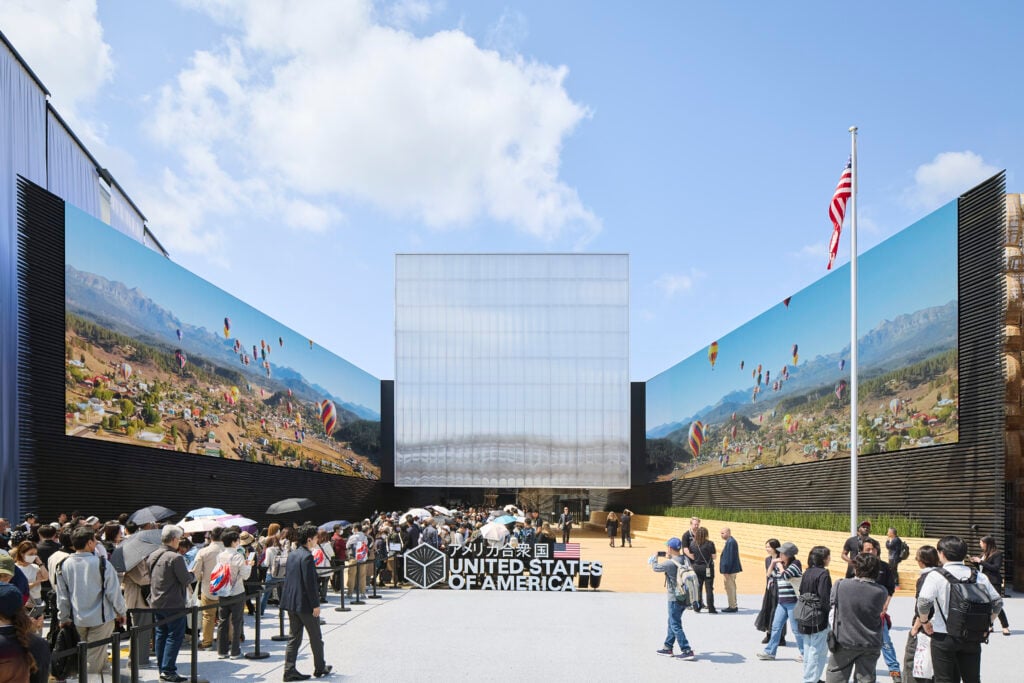

Lessons in Global Design from Expo 2025 Osaka

What this year’s pavilions revealed about culture, sustainability, and the future of architecture.

Projects

A Sustainable Expansion Revitalizes a Century-Old Quebec Retreat

In its extension to a family’s country residence, Pelletier de Fontenay sought to cohere parts and climate-sensitive approaches, old and new.

Viewpoints

What ThinkLab is Hearing: Inside the Tariff Turmoil

Discover unfiltered insights from industry leaders, revealing how tariffs are reshaping strategy, pricing, and partnerships.