March 18, 2014

The Fabricator That Serves Manufacturing Needs of Behar and Newsom

A third-generation aluminum fabricator reinvents itself by opening up to design.

Courtesy Alex Blair

One of Neal Fay’s several collaborations, the EXO installation by Dosu featured an innovative assemblage technique using machine-cut aluminum and heated bimetal.

In 1945, when Neal Fay Rasmussen was looking for a place to base his manufacturing start-up, he knew that he didn’t want to be in Los Angeles—the city where he’d spent much of World War II working at Lockheed and raising a young family. “My grandfather was a very high-style dude,” says Alex Rasmussen. “He said, ‘I want a place with cachet. I want an address that means something.’” Drawn to the golden coastal city of Santa Barbara by its la dolce vita reputation and the fact that it was a launching pad for the fashion house Salvatore Ferragamo, the elder Rasmussen put down the roots of what would grow to be a 50,000-square-foot factory just minutes away from the region’s lush vineyards and beachfront homes.

The company, called Neal Feay—Rasmussen’s early training as a typesetter instilled a love of symmetry that led him to add the ‘E’ to his name—started out making bracelets. Taking advantage of the post-war glut of aluminum, they were anodized aluminum cuffs, stamped with midcentury names (Doris, Betty, June) that sold like shiny, silver-colored hotcakes at Neiman Marcus. “Bracelets are what built this company,” Alex says. As Neal Feay evolved, it went from designing and manufacturing anodized aluminum bracelets, cigarette cases and matchboxes, to making anodized aluminum parts for hire. Demand was high for the processed metal—which is up to 50 percent more durable than aluminum on its own, thanks to an anodizing process that uses an electric charge and a dilute acid bath to create a layer of oxide on the surface of the metal.

The now 49-year-old scion began helping out around the family factory when he was eight—silk-screening logos onto aluminum parts—and by age 13 he was already programming in machine code. Even as a teenager, Rasmussen knew that he would one day run the factory that his grandfather started. After graduating from USC, he joined his father in the business and soon carved out a niche for himself, steering the company into the design and manufacture of sleek, stylish casings for high-end audio equipment—an industry that was already in love with anodized aluminum, thanks to the work of hi-fi pioneer, Saul Marantz.

By the mid-2000s, high-end audio was 80 percent of Neal Feay’s business. Rasmussen had a sailboat. He had a wife. Life was good. And then: 2008. “It was bloody,” he says. Over a gut-wrenching six-week period, the audio companies that were the core of his business slashed their orders and his firm had to lay off more than a third of its employees. At the start of 2009, the family was tapping into its personal savings to keep the company afloat. But, in the sort of shift that has spawned a tidal wave of TED Talks, with the threat of losing everything came a pivotal “Why Not?” moment.

For years, Rasmussen had been obsessed with glossy design books and magazines, buying them by the armload—sometimes dropping more than a thousand dollars a trip—at Hennessey + Ingalls, an art bookstore in Los Angeles. “I wanted to meet and work with the people I’d been reading about all by myself,” Rasmussen says. So he invited them in. “I decided that any creative person could have a tour, and that included curators, musicians, sculptors, and designers, because creative people know creative people.” He started with artist friends and their dealers, and—just as he’d hoped—they were excited enough by what they saw to bring in like-minded creatives.

Portrait by Soohang Lee

The second and third generations of Neal Feay: Alex Rasmussen with his father, Neal.

The artists, architects, and designers were wooed both by Rasmussen’s winning combination of brashness, ingenuity, and willingness to experiment, and by Neal Feay’s full suite of capabilities. That 50,000-square-foot facility is like several factories in one. At the center is a warehouse-sized room crowded with vertical and horizontal mills, laser cutters, CNC punch presses, hydraulic presses and more. Here, raw aluminum—which, it turns out, is the third most abundant element on earth, surpassed only by oxygen and silicon—is shaped. As Rasmussen explains it, there are essentially two ways to create an object. “There’s tooled-up design—where you make a tool and you stamp it out—and there’s manufacturing, where it’s all about getting the holes to line up. We were using precision machines to create form, but instead of making objects, we were using much more cut-oriented things to essentially create decoration.” By pushing the limits of CAD/CAM, they were able to develop proprietary machining techniques in a little-explored medium. “We asked, ‘How do you make things beautiful with tools that weren’t really designed to make things beautiful?’” It turned out that designers like Marc Newson, Ross Lovegrove, and Yves Behar were interested in the answer.

Photo by Soohang Lee

Samples from the Neal Feay materials library

Of course, Rasmussen didn’t just wait for the world to come to him. After deciding that he was interested in working with Holly Hunt, where he and his wife had purchased furniture in the past, he received an 11th-hour invitation to a 2011 party where the firm’s head designer, Alberto Velez, was in attendance, and appeared with an especially beautiful audio box that Neal Feay made. “I showed it to him, and he kind of blew me off,” Rasmussen says. Undeterred, he presented Velez with photos of a table that he’d designed as an experiment. It worked, and Neal Feay now makes two of Holly Hunt’s bestselling pieces—the Shadow Dining Table and Shadow Chair. A similar display of brashness led Rasmussen to wangle a meeting with artist Teresita Fernandez. In preparation, he and his team riffed on the jewel-like surfaces that she created for Louis Vuitton, sending her a box of samples. She was impressed, and ended up connecting Rasmussen with Louis Vuitton—Neal Feay’s first permanent, building-sized surface was for the luxury-goods maker’s Toronto boutique.

The voguer-than-Vogue clothing store Opening Ceremony was another one of Rasmussen’s targets. The owners, Carol Lim and Humberto Leon, had just been tapped as the creative directors of French fashion label Kenzo, and Rasmussen came knocking with a series of butterfly studies inspired by Kenzo’s recent ads. “Humberto said, ‘That’s the old guys. We’re not butterflies anymore; we’re cactus!’” The next day, a box of cactus creations were shipped off, and Neal Feay ended up doing cactus store displays for Kenzo boutiques around the world, as well as a series of trays for Opening Ceremony in a beautifully rendered wash of color.

Rasmussen’s grandfather pioneered the process for colored anodizing, which he christened Anofax. The dyeing and the anodizing take place in tandem, in a smaller warehouse adjoining the machine shop. Long, open vats stand in rows and, at first glance, the space looks like it could be some sort of indoor seafood farm. But instead of brine, the vats are filled with either the diluted 15-percent sulfuric acid solution that activates the anodizing process, or with the organic-based dyes used on clothing, which, when applied to aluminum, yield gleaming, cool-toned hues.

Photo by Soohang Lee

The anodizing department

Next door is a silk-screen shop, where logos can be applied to aluminum pieces after they’ve been anodized and dyed, and beyond that is the design studio, where Rasmussen and three design engineers sit facing an indoor skate ramp. Against one wall is a suspiciously familiar table, which turns out to be the prototype of the one that Neal Feay fabricated for superstar designers Marc Newson and Jonathan Ive—the final sold for $1.8 million at the splashy, star-studded RED auction that the pair hosted to fund the fight against AIDS in Africa. Well-worn surfboards stand in one corner. Another wall is lined with aluminum boards leftover from experiments performed by various visiting artists, while banished to an alcove is a supremely ugly blown-glass sailing trophy—all leaping dolphins and overwrought curlicues—awarded to Team Neal Feay for a win aboard Rasmussen’s boat, Free Enterprise. Two of the designers are also part of the crew, and “Wet Wednesdays” are reserved for sailing in the late afternoon. The twenty-first century’s contribution to the encyclopedia of masculine tropes could be illustrated with this band of merry makers—cerebral frat boys who want to get deep into a 3-D model as much as they want to do shots and shred waves. It’s hard to believe that they haven’t yet found a way to turn that trophy into a high-performance bong.

That the RED table rests so casually in the design studio is an excellent representation of how far Neal Feay has come. Today just 30 percent of the business is in high-end audio, and most of the rest comes from partnerships with the kind of designers that Rasmussen could only dream of working with just five years ago.

“I like crazy stuff happening in the building,” Rasmussen says. “That’s why we work with artists. It’s all about cultivating a culture of creativity.” Outsiders can also pose new questions that expand the factory’s capabilities. L.A.-based architect Doris Sung met Rasmussen when she was invited to be part of the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara’s (MCASB) architecture show, Almost Anything Goes—the curator, Miki Garcia, brought all of the participants in to tour Neal Feay. Sung’s firm, Dosu, is research-focused and has been experimenting with the potential of bimetal—widely used for coils in residential and vehicle thermostats—which curves when heated and flattens when cooled.

Courtesy Formlessfinder

The company manufactural the steel trusswork for Formlessfinder’s Design Miami entrance in December.

Courtesy Louis Vuitton

Neal Feay’s first permanent large-scale facade was for the Louis Vuitton boutique in Toronto.

Courtesy Doris Sung

Dosu assembled their EXO installation at the Neal Feay facilities. They used a combination of aluminum and heated bimetal, which snapped in place as it cooled.

For the MCASB show, Dosu worked with Neal Feay to create an eight-foot-high curved cylinder with a bimetal core and an anodized aluminum skin. “With fabricators, they’re not always so supportive towards innovation,” Sung says. “They are not interested in the things they’re not clearly going to gain something out of financially. But with Alex, he was supportive of it as a project of innovation.”

Neal Feay provided the exterior aluminum, as well as giving the Dosu team space to work and access to a laser cutter where they could cut the 288 pieces of bimetal and 48 vertical strips of aluminum necessary for the final structure. Once the aluminum pieces were slotted together, they were hung from the ceiling. “The first time I saw it, it looked like pieces of capellini,” says Rasmussen. It wasn’t until the bimetal pieces were heated one by one in a regular oven, and then put in place by someone standing in the middle of the circle of ‘capellini,’ that the shape began to take on form and mass. The aluminum surface is pulled in tension by the bimetal, stretched out like the string of an archer’s bow. “It seems like a wildly impractical thing, but it’s pretty big and you’re getting a lot of structure out of nothing—this could have shipped to Doha in an eight-foot-long skid!”

Methods of creating structure with very little mass are more interesting to Rasmussen now that he has begun to realize the potential of anodized aluminum to make more than just objects. The facade of the Louis Vuitton boutique represents the direc-tion that he hopes to take the company. They’re also developing facades for Dior and Michael Kors boutiques. “In the last three years, we’ve tripled what it took twenty years to do, just by opening up,” Rasmussen says. “It’s much more collaborative. For twenty years it was me thinking, and other guys helping me think, and now we’ve got guys like Marc Newson and Jony Ive who want to do things, saying ‘What if we did this with your ideas,’ and, ‘I want to do this; do you have any ideas?’ I think that’s far more exciting.”

Click through to the next page for a selection of Neal Feay’s collaborative projects.

All product photos courtesy Neal Feay, unless otherwise noted.

Lucing Light Fixture

Inspired by moonlight and created in collaboration with Zorine Pooladian, a young Art Center College of Design grad.

Courtesy Alex Blair

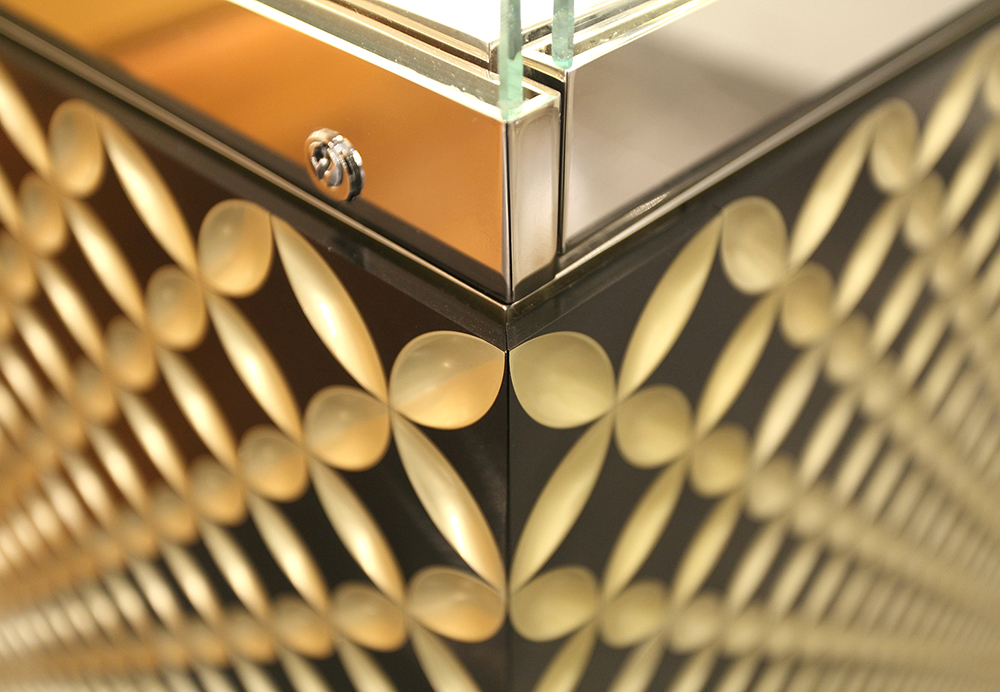

Louis Vuitton

Neal Feay’s first permanent large-scale facade was for the Louis Vuitton boutique in Toronto. The facade has a tactile, almost three-dimensional quality.

Pink Void

This light is the first in a series of limited-edition production pieces designed by architect Johanna Grawunder.

Courtesy Tedd White

Rainbow Tray

These custom anodized trays were done for the retailer Opening Ceremony, also in collaboration with Leon and Lim.

Kenzo Store Display

An early maquette of the display. It was the French company’s first project with fashion stars (and Kenzo creative directors) Humberto Leon and Carol Lim.

Courtesy Holly Hunt