May 2, 2014

George Matei Cantacuzino, Romania’s Forgotten Modernist

A new book explores the Romanian architect’s “hybrid” work, which stressed an organic conception of modernism while still retaining some local tradition.

Every article on the Balkans seems obliged to start with a commentary on the region’s tangled past. Dan Teodorovici’s George Matei Cantacuzino: A Hybrid Modernist (Wasmuth, 2014) is no exception. As Teodorovici states in his introduction, “The linguistic complexity of East-Central Europe is no more mappable than the stylistic plurality of its architecture; happily, some are now endeavoring to try.” Tedorovici’s subject is George Matei Cantacuzino, an architect of great consequence in Bucharest but of little note elsewhere. He is also an overdue beneficiary of a revived interest in that jumbled set of states and histories.

The architecture of the Balkans received, until recently, little attention beyond its national boundaries. Even expansive critics like Jean-Louis Cohen devoted but a few paragraphs to the region in his encompassing primer The Future of Architecture Since 1889. In fact, there are only a handful of English-language accounts of modern Balkan architecture, and those there are—discounting studies like Romanian Modernism: The Architecture of Bucharest 1920-1940, Modernism in Serbia:The Elusive Margins of Belgrade Architecture, 1919–1941, and, more recently, Modernism In-Between: The Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia—are often of a general, even cursory nature. This is unfortunate because many of these states came of age at a precisely fortuitous historical moment; vernacular traditions were generally too complicated or aged to become ossified orthodoxy (rebuilding, say, Serbia in the style of the 14th century Nemanjic dynasty wasn’t really a workable proposition even for the most avid revivalists). Modernism, on the other hand, offered just the sort of supple and physical identity that new states were seeking. Yet, Cantacuzino’s embrace of modernism differs than that of his contemporaries. While Tristan Tzara and Brancusi exported an utterly new vision to Europe, Cantacuzino stressed an organic conception of modernism, entirely open to worldwide material advances while retaining some memory of local tradition.

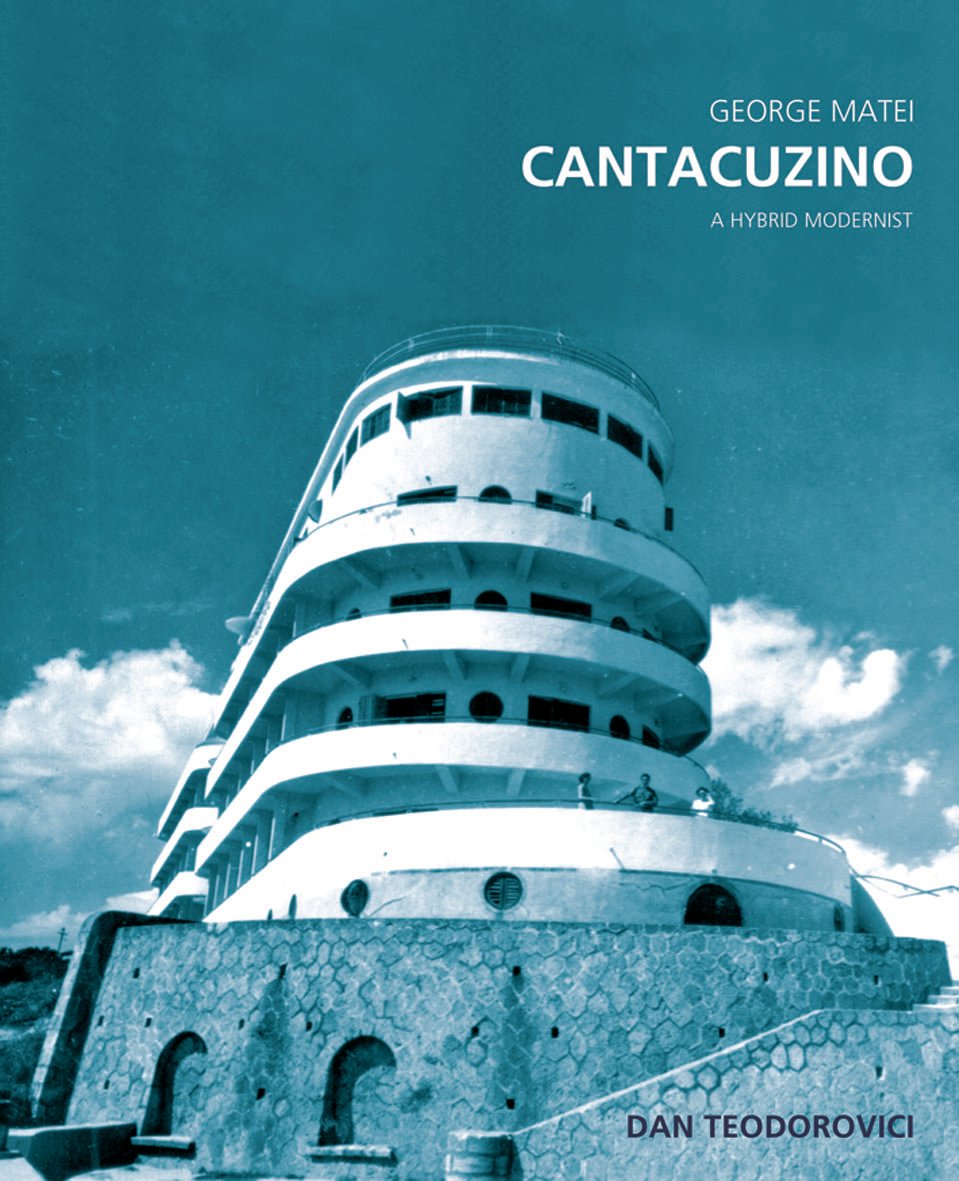

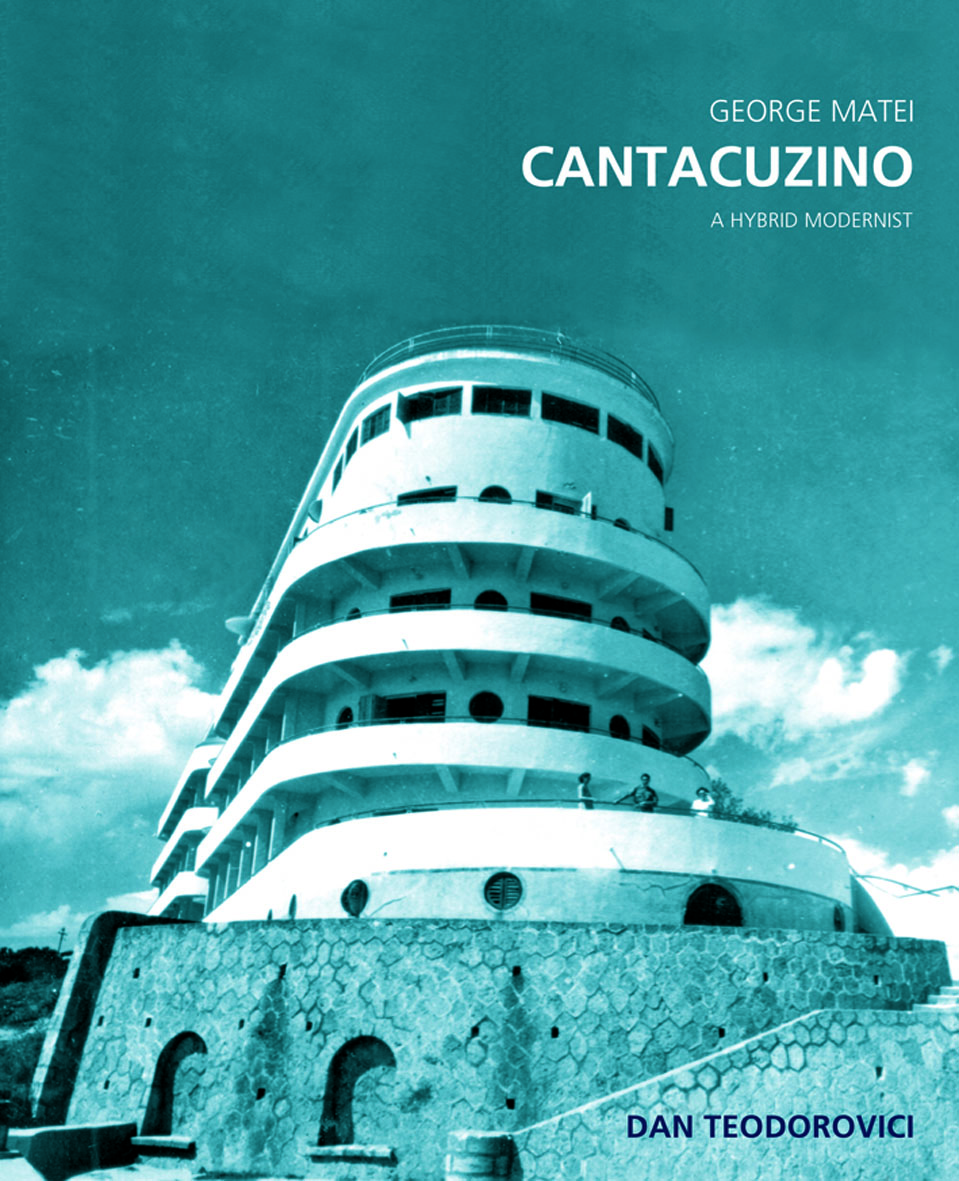

The cover of George Matei Cantacuzino: A Hybrid Modernist, featuring the Bellona Hotel at Eforie (1933)

Cantacuzino’s early life is an archetypal tale of Eastern European cosmopolitanism. Raised a diplomat’s son in Vienna, speaking German, French, and Romanian, he continued his primary schooling in Montreax, and then on to an architectural education at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His studies stretched over a period of nine years, from 1920 to 1929, during which he wrote the first article on Romanian architecture published outside the country.

Soon after, Cantacuzino began work on several country estates, channeling “late Byzantine-Wallachian and aquatic Venetian architecture” as well as contemporary influences. In one of his first projects, the rebuilding of an 18th-century palace, he resisted pressure to restore the complex to its former glory, opting instead to substitute simple brick where evidence of its initial appearance was absent. Another estate, an entirely new construction, featured slim doric columns that played off unornamented stone.

Carlton Building in Bucharest (1936)

But the young architect’s attentions were soon turned elsewhere. Romania was poised in a unique situation amongst nations turning to modernism for their construction needs. Swollen in size after the First World War, it lacked much of an urban lower class and the according political establishment that drove large-scale workers housing projects across Northern and Western Europe. Private commissions and government buildings were the core of available work. And Bucharest, a not-especially large, if generally handsome city, found itself suddenly a crucible of extensive construction. Its older form had been inspired by Paris but for this new age of construction little Haussman-like demolition was required; dense boulevards of art deco and idiosyncratically modern towers simply sprang up in a short span.

The Hotel Rex in Mamaia (1940)

70 of Cantacuzino’s projects were built within Bucharest, which he, along with a handful of other Romanian luminaries, namely Horia Creanga and Marcel Janco, succeeded in substantially altering in a span not much longer than a decade. These began as stately Beaux-arts and Neo-Renaissance structures but soon grew sleeker. White moderne walls and curves, casement windows, window columns, wedding cake-like setbacks, and other modernist staples were tempered with local touches, such as balconies, ornamental cornices, fanciful stonework.

Cantacuzino’s later years put a tragic close to a period of vibrant productivity. His status as a liberal-minded architect and public intellectual did not serve him well in the political environment that arose after Romania’s fascist turn in the late 1930s, nor did he fare better under Communist rule. A history of tolerance and democratic enthusiasms landed the architect in prison once during the fascist period and twice under the Communist state, on the second occasion conducting forced labor on the Danube-Black Sea Canal. He served briefly as an inspector in the Department of Historic Monuments, before being sacked. An exhibition of his work in Bucharest was shut down on its third day. He landed, ultimately, in the smaller city of Jassy, serving as “unofficial diocesan architect” until his death in 1960. And if death could not seem an ultimate indignity, a number of his works were lost to Ceausescu’s brutal remodeling of Bucharest in the 1980s.

Apartment building in Bucharest, 29 Brezlanu Street (1934)

History came to offer a kinder verdict than Communist Romania did. Cantacuzino gradually became recognized as a seminal figure in a fascinating local strain of European modernism, and has now broken into the realm of the English language monograph. Teodorovici’s account is an intriguing one, but not without its quirks. It’s somewhat disjointed in form, separating a biographical account from a critical essay on his architecture; these tasks are different but they rarely require so hermetic a separation. Some other features are distracting; on countless occasions the author notes, when discussing individual buildings, that another figure “probably” inspired Cantacuzino. In the absence of documentary evidence there’s always some speculation about influence but this form of guesswork can become easily rote. There’s no shame in dodging the “probably” and simply pointing out that a building may resemble another without the need to resort to conjecture.

These aside, the book is a strong volume, offering a sharp account of Cantacuzino’s life and work, accompanied by a fine photographic index of his buildings and ample photos of the broader backdrop of Romanian architecture, both historical and contemporaneous. Nearly all recent closer looks at the grand vernacular variety that is modernism around the world are welcome, but especially when they furnish sights like these.

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn. He writes the “Spaces” column for the Wall Street Journal and has written otherwise for The Daily Beast, The Awl, Bookforum, and The Millions on urban policy, cinema, historic preservation, and literature, and Metropolis on Long Island Modernism, Boston city planning, the preservation of Brutalism, and a variety of other topics.