October 13, 2022

These D.C. Art Installations Point to More Than High Water Marks

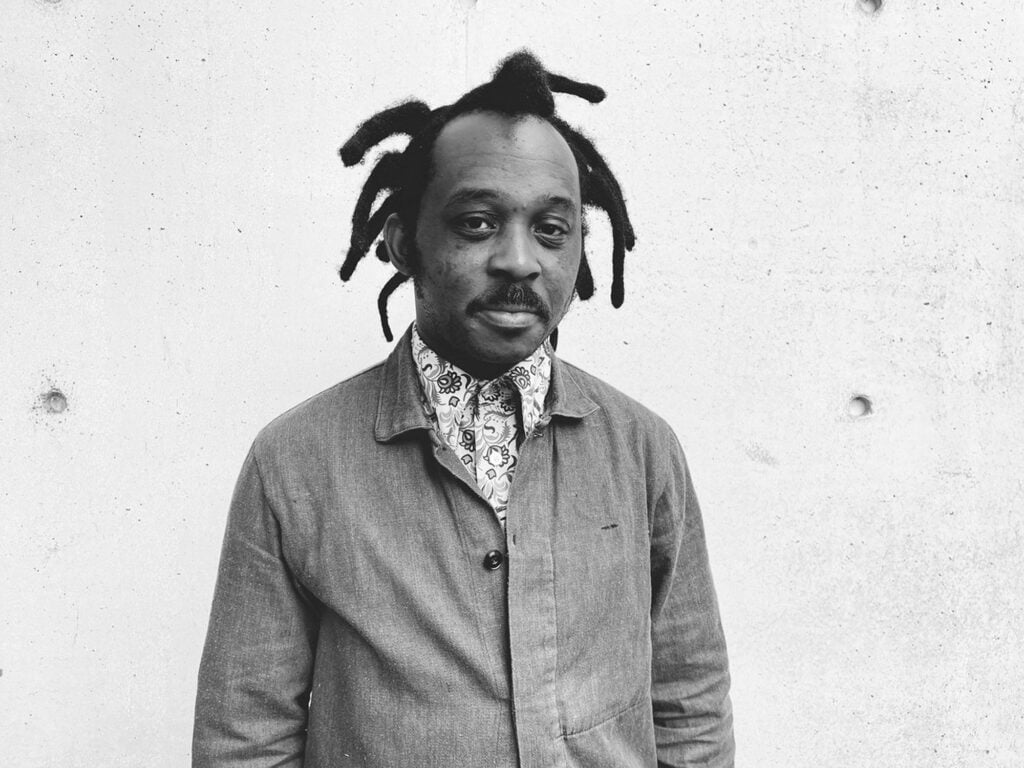

For their first two installations, Curry J. Hackett (top) and Patrick McDonough (bottom) conducted research to determine which Washington, D.C., neighborhoods most needed their bold, friendly reminders, selecting Marvin Gaye Park and Kingman Island, serving predominantly Black neighborhoods along tributaries to the Anacostia River.

“Architects are always talking about climate change, but those conversations get mired in credentials, performance, or LEED certifications—like the conversation is being had on behalf of the public, without the public. What we’re trying to do is engage them directly and offer an incentive to make choices,” Hackett says. Freedom to select the sites (the first two totems are in Marvin Gaye Park and Kingman Island, predominantly Black neighborhoods) got McDonough and Hackett envisioning a gradual expansion of the program throughout the city’s entire 100-year floodplain. “That,” Hackett says, “is a different kind of agency.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

Archtober Invites You to Trace the Future of Architecture

Archtober 2024: Tracing the Future, taking place October 1–30 in New York City, aims to create a roadmap for how our living spaces will evolve.

Projects

Kengo Kuma Designs a Sculptural Addition to Lisbon’s Centro de Arte Moderna

The swooping tile- and timber-clad portico draws visitors into the newly renovated art museum.

Products

These Biobased Products Point to a Regenerative Future

Discover seven products that represent a new wave of bio-derived offerings for interior design and architecture.