August 17, 2021

A Senegal Hospital Extension Responds to the Local Context

Designed by Manuel Herz, the maternity and pediatric hospital expansion aims to transform the conditions under which patients receive care.

In 2017, the executive director of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Nicholas Fox Weber, launched a competition to design an extension to a pediatric hospital in Tambacounda, Senegal. Initiated by Le Korsa, a philanthropic arm of the Albers Foundation that has been active in eastern Senegal since 2005, the project was aimed at radically transforming the conditions under which mothers and newborns receive care in the region.

An invitation found its way to Switzerland-based architect Manuel Herz, who has done extensive research on African architectural contexts. In 2015, he authored the first volume of African Modernism, which explored Modernist architecture throughout Ghana, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, and Zambia. (A second volume is currently in the works.) One year later, he presented his research on the refugee camps of the Western Sahara, which host the Sahrawi population in the border zone of southwestern Algeria, at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, marking the first time a nation in exile was represented at the event.

Upon receiving Fox Weber’s message, Manuel Herz hesitated and initially declined—but ultimately he submitted an entry that focused not on a final project but on a proposed approach to the hospital.

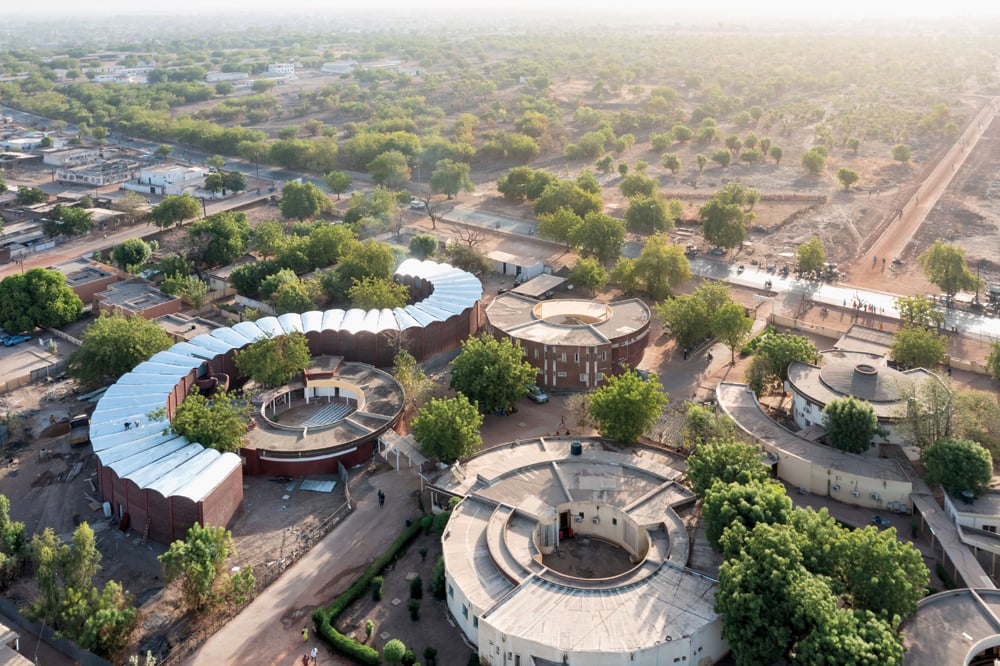

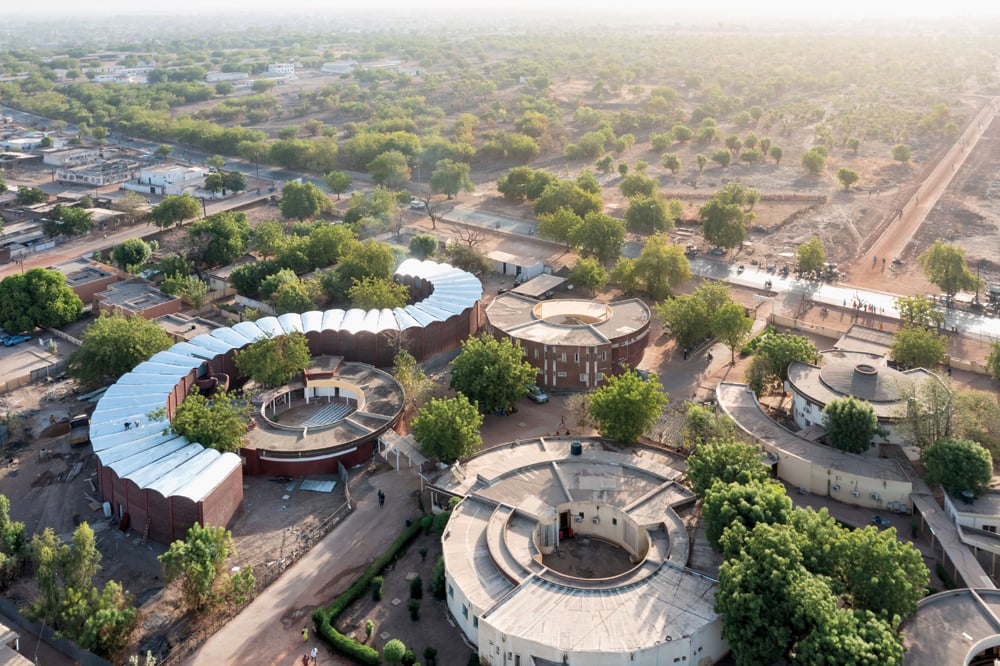

A few weeks later, Manuel Herz found himself in the streets of Tambacounda, in eastern Senegal, conducting the first step of long-term research in the region. He visited the existing hospital buildings—a set of circular constructions that he estimates are from the 1970s or ’80s—endured harsh 100-degree-plus summer days, studied local construction techniques and materials, and, in meetings with local stakeholders and hospital staff, compiled a series of sketches detailing their spatial and programmatic needs, which then became the basis for the new building’s design.

Herz’s concept called for a curvilinear building that embraces the existing round structures, “a building that is as long as possible and as thin as possible,” he says, “with a one-sided structure where we have a long corridor and all rooms to one side.” This kind of spatial organization allows cross-ventilation while creating a variety of outdoor and indoor courtyards, and nooks with benches and large corridors that act as gathering spaces for patients’ families and visitors.

Other passive ventilation measures are embedded in the construction’s doublevaulted brick-and-metal ceiling, and in the perforated brick screen that clads the undulating structure. Together, they work to create a breeze in what Manuel Herz calls “a surprisingly windless area.” The ground floor hosts the maternity clinic and operating rooms, and the upper floor harbors the pediatric clinic; the only spaces requiring mechanical ventilation are the intensive care units and operating rooms.

After bringing the first concept back to Tambacounda, Manuel Herz recalls hours of transformative discussions with detailed feedback from local authorities and hospital staff—from the director, Dr. Thérèse-Aida Ndiaye, to the doctors, midwives, and janitors—which helped round out the final design. Construction was conducted in close collaboration with local doctor and contractor Dr. Magueye Ba, who supervised the process, including the brickwork: Workers produced 50,000 bricks for the project, 100 per day, over 500 days, which follow the local typology of hollow bricks. The hospital expects to start receiving patients this summer.

Herz is now working on an additional project in the hospital complex for staff accommodation, allowing visiting doctors from the capital city of Dakar to extend their stays and bring their families. In the meantime, the signature brick pattern has taken on a life of its own, with Magueye Ba using it for other buildings in the surroundings. In this dynamic, Herz’s project begins to exist as part of a network—of stakeholders who become coauthors in the intervention, and of buildings themselves, as his extension touches upon existing structures and conditions new ones. “The project becomes not only an architectural intervention but a territorial intervention,” Herz says, noting the project’s economic impact in the area. “This kind of coherence is incredibly important to make sure the building really is accepted by the population.”

You may also enjoy “Why Aren’t Black Firms Working on Memorials to Slavery?”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.