January 18, 2016

Q&A: Lowline Founders Dan Barasch and James Ramsey

The duo discuss the merits of crowdfunding, the challenge of growing plants underground, and the importance of cool.

All photography courtesy the Lowline

The Lowline could be New York’s next great attraction, when and if it opens in 2020. At least, founders Dan Barasch and James Ramsey think so. Visitors to Manhattan’s Lower East Side can get a glimpse of the subterranean park at the Lowline Lab exhibit, which realizes a small fragment of the technologically innovative project. Metropolis‘s Mikki Brammer talks to Barasch and Ramsey about crowdfunding, growing plants underground, and the importance of cool.

Mikki Brammer: You launched your first Kickstarter a few years back to great success. Last summer, you followed that up with a second, even more successful Kickstarter drive, which closed out at around $224,000. In the intervening time there have been no shortage of criticisms of crowdsourcing public projects. How do you think the great success of the more recent campaign refutes those criticisms?

Dan Barasch: Our Kickstarter campaign back in 2012 was really the first time that we had reached out for funding in a real public way. We barely had any resources and I was moonlighting—I had a full-time job at that stage. We turned to Kickstarter because we didn’t really know where else to turn and it was a way to raise critical funds for our next project and the next stage of our effort, which was the ability to build a full-scale technology exhibit and prototype to demonstrate our idea and share with people how the idea could actually function.

The actual reality of a project like ours is that there is so much work that needs to get done that actually makes no sense for a crowdfunding platform. All the behind-the-scenes scientific research, the design work and the nuts and bolts of making this thing happen politically and from a community and grassroots standpoint. It’s hard to do that kind of stuff on a crowdfunding platform. But we first went to Kickstarter for a very real thing that we were building, which was our very first technology exhibit in 2012 [the Imagining the Lowline exhibit], and that really gave us the funding, the visibility, and, frankly, the confidence to build it later that year. In 2015, we returned to Kickstarter, again having been encouraged by people who are great experts at crowd-funding, because we were at a stage where we were building something public—the Lowline Lab, which is a longer-term version of the exhibition but also reflecting a much more sophisticated scientific approach to the thing we’ve been designing over the course of the last couple of years. And it seemed to resonate with people both times and they wanted to support us.

James Ramsey: Just to elaborate a little bit on that also, this is a pretty decently sized urban design project, and crowd-funding certainly has its limitations, of course, but in this particular instance—unlike most public works projects—there was no RFP process to start, and the mayor didn’t issue a request or anything like that. It’s really just been Dan and me trying to push forward this idea for something awesome. So kind of a necessary part of that is building a ground swell of support, and crowd-funding in general is completely in sync with the nature of this particular project.

MB: Dan, you mentioned the Lowline Lab exhibit, which was launched in October inside an Essex Street warehouse in the Lower East Side. In what ways is the exhibit actually a “laboratory”?

DB: The Lab has allowed us to conduct valuable research on the viability of the project, across three important categories: remote solar technology, horticulture, and year-round place-making. Our measurements to date indicate that our technology solution delivers the quantity and quality of light to enable photosynthesis underground, which is an impressive feat. Our landscape design collaborators at Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects have been highly successful at fostering over 50 species of plants in a darkened environment, providing valuable data on the plants likely to thrive underground. And survey data conducted among visitors points to some very interesting trends; for example, we are attracting primarily a younger demographic (19-34) and nearly half of visitors have never visited the Lower East Side, meaning we are bringing valuable, youthful traffic to the neighborhood. The Lab has solidified the already impressive levels of support we have received so far, and has allowed us to prototype the technical and social dimensions of the future Lowline, while gathering consistent and steady feedback—it’s a rare opportunity in public design.

Barasch and Ramsey worked with architect Signe Nielsen in creating the small landscape, which integrates more than 65 species and 3500 plants. The Lowline Lab tests which plants can flourish in the subterranean environment.

MB: And how many visitors have been through the Lab since its opening?

DB: We have been thrilled with the Lowline Lab’s impact to date. We have received over 20,000 visitors at the Lab on weekends, and we have hosted dozens of youth education workshops in the site during weekdays. Given that we hope to keep the Lowline Lab open throughout most of 2016, I think we can anticipate over 100,000 visitors at the Lab, and over 2,500 kids who take advantage of our interactive education offering.

MB: The major innovation behind the Lowline is its lighting technology, which makes photosynthesis possible underground and what you’ve called “subterranean horticulture.” The Lowline Lab feature a landscape with several different species of plants. How have they held up over the last few months?

JR: Some have absolutely thrived, enough so that we are continually experimenting with new species, as well as plantings in earlier stages of growth. Some have declined as well, so it’s been a learning experience, but on balance, the great majority of our predictions about plant growth have worked out so far.

It’s not a secret that, in New York City, sometimes getting the ball rolling can be a time-consuming process. It’s a place that a lot of people call their home and they’re fiercely proud of it. Add to that the fact that this is a project that is unlike anything else that has ever existed in the world and that kind of spells out how we’ve spent the past few years, not too mention what we plan to spend a large portion of 2016. In some respects that’s a bit of a mixed blessing because we’re building something the likes of which no one has ever seen before, and in order to do that correctly, we have to do our homework. All of those intervening years since thinking of the idea and lobbying for its viability have been a steady hum in the background of research and design work that will ultimately lead us to create a successful project. The idea itself is about adding a new, cutting-edge technology to this abandoned space at its most fundamental level. We’re breaking new ground literally every day. It’s exciting work and it’s ever-changing, but it’s great that we’ve been able to have something of a running start.

Dan: And when we say “we,” it’s tempting to imagine that it’s just James and me in a room working with white lab coats. But one of the things I’m most proud of is that we’ve built up a really amazing and huge group of supporters—not just the Kickstarter backers and donors—but we also have a board of directors from a wide variety of sectors, who are people with really deep expertise. And we have community organizations that are really advocating for us. We’ve been working with kids in the neighborhood, and schools, for the last couple of years. People have gotten behind the project in a really personal way. What is maybe our biggest accomplishment is that a lot of people have been inspired by the project and have expressed a willingness to help in whatever small way that they can. That is bigger than the idea itself and the stuff we’ve been able to accomplish that relates to fundraising, or scientific discovery, or anything else.

Since opening in October, the Lab has been the site of dozens of youth education workshops—all part of a greater community outreach strategy.

MB: Can you tell us how you’re collaborating with a South Korean company on realizing the project’s sunlight delivery system that’s at the core of the project?

JR: About two years ago, I got a call out of the blue from a South Korean company called Sunportal and they were working on a heliostatic technology that was almost exactly along the lines of what I was working on in terms of a general theme. And out of the dozen or so companies in the world who do this, I hadn’t been happy with any of them—they weren’t performing it in the way that I had envisioned. Add to that the fact that they had actually ferreted out the supply lines and done the homework to work out how to execute it and had actually done it once or twice, which is pretty stunning. We’ve since taken multiple trips to South Korea to examine, test, and vet what it is they’re working on and we think now that we can customize and adapt a lot the stuff that they’re doing for our own purposes, without too much pain. We can integrate their systems into ours seamlessly and have it operate at an efficiency that is well beyond what anyone else in the world is doing.

MB: How have your ideas of what Lowline should be changed since the first iteration in 2011? Or have they remained the same?

JR: Part of last few years has been making a lot of inroads in talking to various people within the community that the Lowline is located in. In that time, people have voiced their opinions one way or another about what they need what does and doesn’t fit. A lot of that has played directly into what is kind of custom-crafting a public space that is particularly suited to this community. In addition to that, it’s a large enough space that we can embrace any number of design elements. And as we learn more about the space and how it works, we can actually have our cake and eat it too in some respects, because there’s an embedded level of flexibility in how we use and program the space. But there’s also enough specificity that we can theatrically craft the experience and give people something that’s unlike any experience they’ve ever had before. You’re walking through an underground jungle—that’s pretty cool. As a design experience in and of itself, it’s something we have to embrace as part of this project, or else it’s kind of a failure.

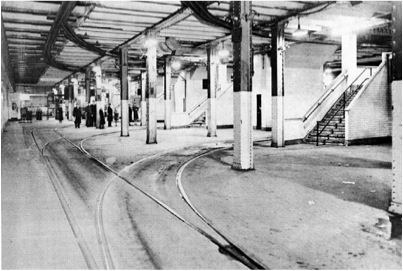

The one-acre Williamsburg Bridge Trolley, now abandoned, can be glimpsed from the platform of the Essex Street subway station.

Barasch and Ramsey hope to convert the space into an “underground jungle” that would also be suitable for events and performances.

MB: What stage is the overall project at now?

DB: The project has now been endorsed by every elected official and we have an active dialogue with the City of New York and the New York Mayor’s Office, and the MTA, which currently holds the master lease on the site. In fact, we are currently responding to a city-led request for expressions of interest (RFEI) process that is meant to determine what the future use of the site will be and who will be developing it. That’s the big picture, but the intermediate steps that we’ve taken have been that James’s team has done some pretty extraordinary breakthrough research about how, specifically, natural sunlight can be delivered underground. And over the last couple of years, that’s been advanced, along with the design, in order to prepare an actual proposal to get everybody onboard. So it is, in every sense of the world, a cutting-edge and innovative approach.

MB: Beyond the technological, what other challenges lie ahead for the project?

DB: The challenges we really face as an organization are technology, research, and fundraising. Certainly one of the biggest things we’re focused on is how we raise money for it. It’s not as if we can simply reach out to the city to pay for the entire project—there’s an expectation that it will need to be a public-private partnership in order to get it over the finish line. We’ve looked at a roughly $60 million capital budget and we’re examining that right now to really ensure that it’s how much money we’ll need to raise. I think a significant amount of that money will need to come from the private sector and private individuals. So that’s a huge amount of work for any organization to really pull together those resources and that’s why we’re spending so much time on it and why it takes so many years to make it happen. The other challenge, which isn’t related to the technical work, is the politics of it all. The project is within New York City but we’re also mindful of regulations and challenges that are at the state level. It’s also next to a really critical piece of transportation infrastructure—the Williamsburg Bridge—so we have a lot of considerations to address. From a political standpoint, we need to achieve the right balance between our design priorities, our social priorities, and the constraints on the political side.

JR: And just to add to that, the technical research that we’re doing can be looked at as the raw horsepower that allows us to execute a design vision and craft how that experience actually is manifested in space. The more we learn about the limitations or the possibilities that the technology actually engenders, the more we can understand how to use these tools to craft that vision.

MB: Do you see the work you’ve undertaken over the course of the Lowline’s life to be indicative of a new kind of architectural practice?

JR: In one respect, the way that we’re approaching the project in general is basically from the bottom up and varying degrees of that have been done around the world at some point, but maybe not to this level. That in and of itself and the idea of clientless architecture is a pretty strong indication that it’s different from most things. And just in terms of a design vision itself, this is actually using technology in a way that is embracing so many different facets of what we’re trying to achieve, from illuminating historical context to activating a piece of lost infrastructure, to rethinking the way we actually look at our underground spaces, to actually almost creating something akin to a theatrical experience. I think those things all in combination represent something that’s really different from anything else that’s out there. There’s also a very New York–flavored element to our design process; in a city as built up as ours, we are usually made to focus design energy on existing interior spaces, and often less on crafting some sort of sculptural “object” of a building. The Lowline uses this natural affinity as an asset, creating space to inhabit, and an experience, above all things.

DB: I’m not an architect or a designer, so I look at this from a much more basic level. But the way I think about this is that it’s part of a larger story that is actually happening all over the world and certainly in New York City, in terms of reuse and rethinking infrastructure. I think it’s also an encouraging sign that people without a lot of expertise feel empowered to work on these kinds of projects. We’ve had people reaching out to us from all over the world with really interesting ideas. I think what we’re doing is, on one level, very very innovative. It’s basically following in the footsteps of anybody who has wanted to improve their neighborhood and to look at spaces with new creative eyes.