November 18, 2013

Review: Guido Beltramini’s Biography of Andrea Palladio

New book from Lars Mueller to delight the bibliophile architect

It’s no secret that we architects are just as obsessed with books as we are with buildings. We collect them, sometimes we read them, and, not often enough, we talk about them. To indulge our bibliophilism more often and more openly I offer a series of posts about books on architecture, architects, and/or simply architectural ideas.

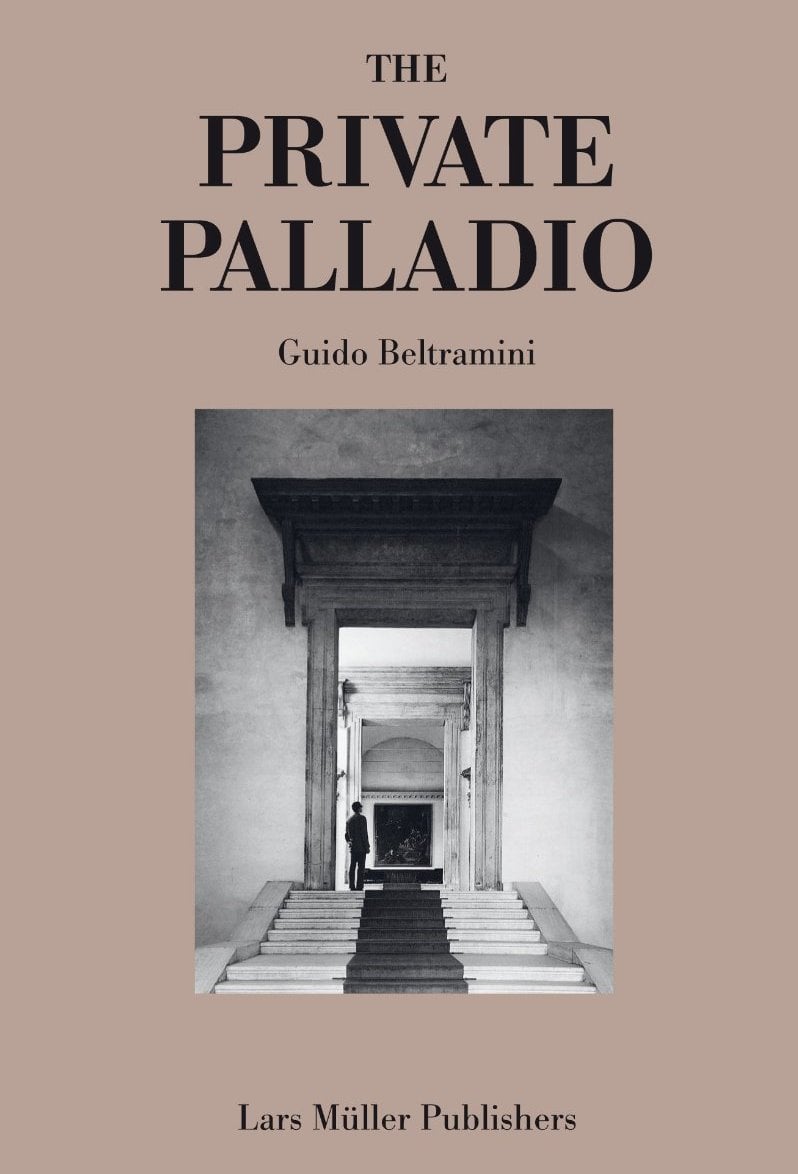

Guido Beltramini’s slim biography of Andrea Palladio, released by Lars Muller Publishers, is a difficult book to get into at first—not because its subject isn’t fascinating (it is), and not because its writing is dry and academic (it isn’t). Getting past the book’s cover takes some effort simply because that cover, on its own, is so seductive.

Glued to its center is a small black and white photograph of the Refectory at San Giorgio Maggiore, which Palladio built in Venice in 1562. Centered in that photograph’s foreground is the refectory’s stone portal, with its massive, brooding entablature casting, and cast in, a deep shadow. Centered again within that portal is a glimpse of yet another portal, similarly designed but fully revealed in light. Through this succession of frames, in the far back, we can make out a roughly square painting, hung from the end wall of the refectory’s long barrel vault.

It’s worth lingering on the cover for two reasons. The first is simply to underscore the book’s tactile quality as a physical object. What could have easily been an image on a glossy dust jacket is instead a separate matte print inlaid into a slight relief panel in the book’s textured cloth binding, which is lined luxuriously with red paper inside. The overall vertical proportions of the book are echoed by the proportions of the photograph, which itself echoes the proportions of the portal it depicts, subtly enhancing the frame-within-the-frame effect.

The second reason has to do with that unnamed square painting hung so far back in the cover’s photograph. Interestingly, the photograph reveals just enough information about the painting to figure out not what it is, but in fact what it isn’t. Its size and barely discernible diagonal composition isn’t enough to give away its identity; nonetheless, it’s enough information to deduce that it is not Veronese’s “The Wedding at Cana,” which was the originally commissioned occupant of that wall and which once filled its entirety (a footnote: the plunder of this 715 square foot, 1.5 ton masterpiece was overseen by none other than Napoleon himself, and is today installed at the Louvre in Paris, where it resides as that museum’s largest painting). As such, the placeholder painting hung in the refectory not only rouses our curiosity as to its identity, it also brings into focus the monumental loss for which it serves as a marker. Before we even arrive at the first page, the cover turns out to be a poignant and exquisitely framed reminder of this absence.

This strategy of marking absence through brief, but highly articulate, moments of material substance proves to be a leitmotif throughout the book. Coming in at just over 100 pages, this is not (thankfully) an exhaustive documentation of all things Palladio. Rather, Beltramini seems entirely comfortable leaving the reader with unanswered questions and enormous blank stretches, selecting only a few discrete points in Palladio’s life and rendering them with extraordinary richness and pathos.

The Wedding at Cana, Paolo Veronese

Those few points are, in fact, searing. Consider, for example, the story of Palladio’s oldest son Leonida who, in an argument over a woman, murders her husband by stabbing him in the face. He turns himself in, is tried in court and acquitted, only to die mysteriously three years later. Or picture in Brescia the smoldering ruins of a burned out Palazzo Della Loggia, and outside, the weeping Palladio, having just inspected the damage incurred to his work.

Portrait of Marc’Antonio Barbaro, Lambert Sustris

The visual illustrations accompanying the text are equally intense. Small but dense with latency, they serve less as direct representations of the written content than as a curated assemblage of found objects, each with its own embedded narrative. As with the absence of the Veronese in the refectory, each illustration—here, an obscured view of Istanbul; there, a marble model of Padua—demands the reader to paradoxically look closer and look elsewhere.

And there are, we learn, so many things to look for. There are cameos by familiar characters like Giulio Romano, but the extent of their correspondence with Palladio remains unknown. The book begins with the mystery of where Palladio was born, and ends with the mystery of where and how he died, and even of where is buried. We aren’t even entirely sure what he looked like.

But the most notable absence in The Private Palladio, it turns out, is of architecture itself. Though there is ample discussion on the fierce passion Palladio had for his designs, and even meticulous documentation on the salaries he received for designing them and overseeing their execution, there is an unbroken silence regarding the work itself. There are no Wittkowerian iterative diagrams, no Roweian ideal mathematics. There is no mention of the weirdly clustered columns at the Palazzo Chiericati, no theory about the surreal corner of the Loggia Capitaniato.

It’s clear that this is no casual omission. And for readers looking for new analyses or revelations on proportions, typological inventions, or the politics of urban form—that is, for those of us more interested in architecture than history per se—this book will provide few answers. Instead, it will obliquely, insistently, color the ways in which we continue to look elsewhere. That strange view of Istanbul, tucked into a portrait of one of Palladio’s clients, will haunt the way we re-examine the campaniles—minarets?—of Il Redentore. A close reading of architecture, this book is not, and nor does it purport to be; but in searching for one that is (and there are certainly plenty), we now have certain vivid markers to guide our way.

Before reading The Private Palladio, we might assume that the title refers to the architect’s private life, which the book promises to reveal. Then, halfway through, we might change our mind; perhaps the title refers to all that remains private to Palladio alone, so little to which we are actually privy. There is, however, a third, though admittedly implausible, thought which stirs upon finishing the book: That with the details we have, we can frame the absences of the details we don’t; and in that space, impose the project of our own private Palladio—just as we might hang a painting in the Refectory of San Giorgio Maggiore.

All images courtesy FXFOWLE Architects

This post first appeared on FXFOWLE’s blog, click here to read more.

Austin Sakong joined FXFOWLE in 2013, and is currently working on a new campus for Al Jamea Tus Saifiyah in Nairobi, Kenya. He received his BArch from the Cooper Union in 2004, where he discovered Emily Dickinson; and his Masters of Science in Architecture and Urban Design from Columbia University in 2011, where he discovered David Harvey.