November 21, 2023

Are Shipping Containers the Future of Affordable Housing?

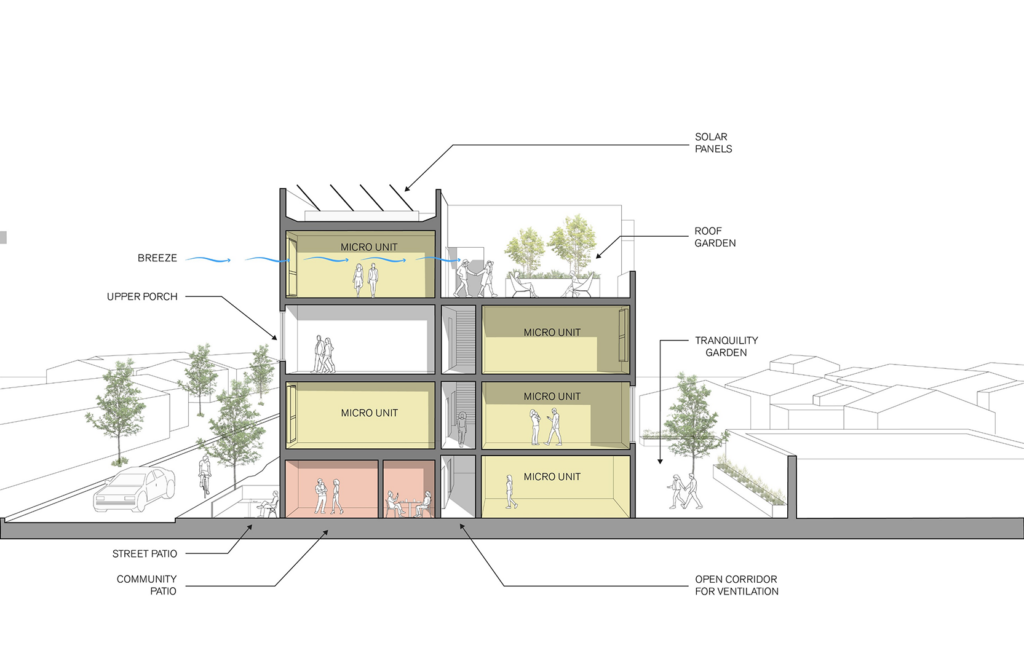

The complex also includes a community room, laundry room, service provider offices, and bicycle parking, not to mention a tranquil rear patio and a sunny rooftop deck. Since few of the residents drive, there is only one parking spot taking up space.

The rooftop garden, with its planter boxes and cozy furnishings, is especially charming, affording panoramic views of the neighborhood, including a few affordable housing projects that are not quite as inspired. One tenant, Hubirasi Perez, says he is constantly up there, getting his needed “chill time.” Perez suffers from severe kidney problems, and couldn’t get in line for a transplant until he had a home like this. (Perez and his wife had been living in their car.) Now he’s clear for a transplant, and just having a bed and a shower are blessings. “It’s the best,” he says of his space. He likes to look at the mountains from his window, especially when the sun comes out.

Tenants gather at a monthly meeting with community director Jermela Booker to air issues and get time together. “A lot of people here had no structure,” says Booker. “This home has helped them grow and become independent. But they can still reach out when they need help. They can feel ok to be vulnerable.”

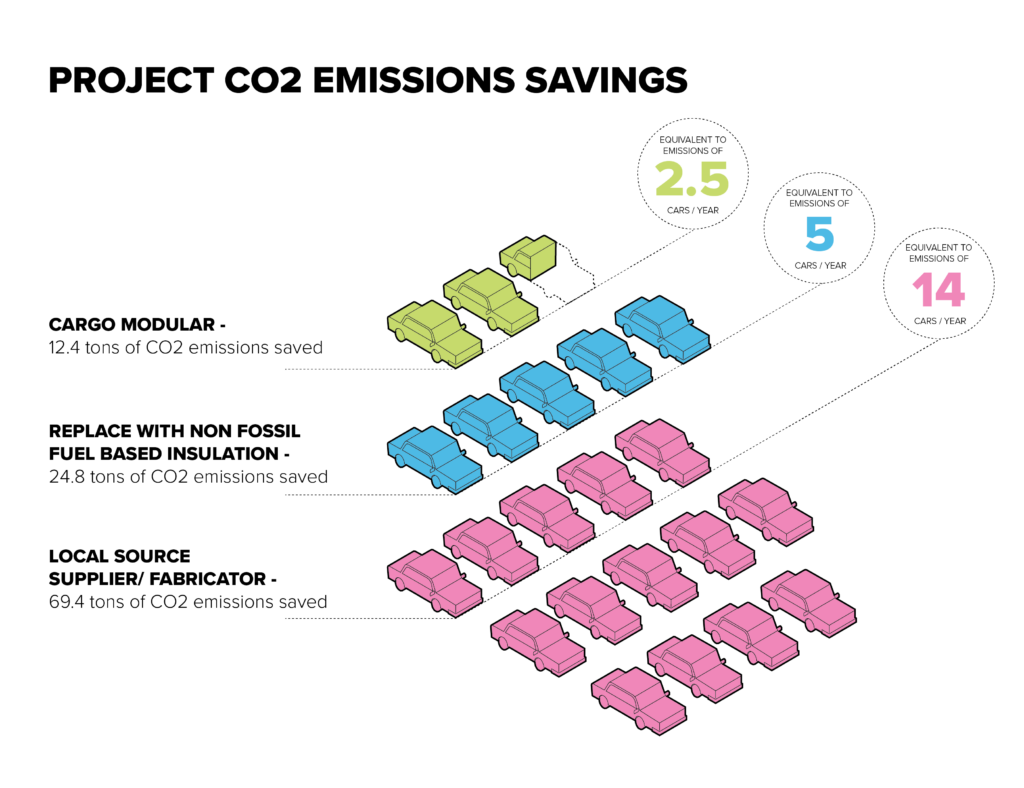

This modular home could become a model for more affordable properties, say Studio One Eleven. Employing the container modules, says the firm, saved about 12.4 tons of CO2 emissions, and cost 10 to 15 percent less than conventional methods. (The cost was about $420,000 per unit, making it much more cost effective than many local affordable projects.) Substantial energy savings come from rooftop solar panels and passive strategies that maximize shading and allow air to flow freely. Open stairs at each end of the building, in conjunction with open corridors provide cross-ventilation and encourage tenant use to engage in a healthy lifestyle.

But because of the many shortcomings around affordable housing, say the architects, the project was much less efficient than it could have been, making future residents wait months and months longer than they should have. On top of unavoidable issues like COVID and its supply chain and staffing problems, local bureaucracy, says firm design director Michael Bohn, had no tolerance for even the slightest irregularities. For instance, accessibility clearances were off by less than a quarter inch in both the stairs and in kitchens. Both had to be ripped up and constructed again.

“We’re not airplane engineers,” argues Bohn, who understands why the rules are in place, but worries the pendulum has swung too far. “It’s missing the forest for the trees,” adds Greg Comanor, partner at the project’s developer, Daylight L.A. “I’m all for accessibility and creating housing options for all, but the city has tied its hand behind its back because there’s little flexibility. We’re being wasteful.”

Bohn and his colleagues recently authored a letter to L.A. Mayor Karen Bass outlining “Ten Points” to improve Affordable Housing construction. These include eliminating off-site improvement costs, incentivizing adaptive reuse, allowing reasonable accessibility tolerances, and encouraging modular by making streamlining local approvals—which in California are much more burdensome than those at the state level. (The state deputizes third parties to approve modular projects in the factory).

Comanor adds that the public sector should also try to support factories that help produce modular affordable projects. “It’s really hard. The economics are not favorable. But I do think it’s an incredible tool and it’s going to get more ubiquitous. That being said, it will take public support.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

BLDUS Brings a ‘Farm-to-Shelter’ Approach to American Design

The Washington D.C.–based firm BLDUS is imagining a new American vernacular through natural materials and thoughtful placemaking.

Products

Discover the Winners of the METROPOLISLikes 2025 Awards

This year’s product releases at NeoCon and Design Days signal a transformation in interior design.

Projects

KPF Reimagines the Arch in a Quietly Bold New York Facade

The repetition of deceptively simple window bays on a Greenwich Village building conceals the deep attention to innovation, craft, and context.