June 30, 2022

Los Angeles Architects and Leaders Take on Their City’s Homeless Crisis

Sam Lubell: Los Angeles has arguably the largest homeless crisis in the country. There’s a profound lack of resources along with deep systemic challenges. Before we talk about some of the solutions, I want to talk to you about the issues within the built realm driving the crisis and stymieing efforts to solve it.

Christopher Hawthorne: One fundamental challenge is that we don’t, in Los Angeles, have a structure of creating public housing or social housing. Going back to the 20th century, there has been among political elites here a very strong aversion to the idea that Los Angeles should produce public housing or social housing. Right after World War II we came very close, but thanks to the influence of the Chandler family (owners of the Los Angeles Times) and others, we turned pretty dramatically away from that idea.

There is now proposed legislation in Sacramento called AB-2053 that would create a California Housing Authority. But the status quo in Los Angeles is something quite different. That means that though we have had very strong support from voters in funding permanent supportive housing, the money that we have raised goes into a very complex and challenging system.

Measure HHH, for instance, was a 2016 city ballot measure, accompanied by a similar measure at the county level, that raised $1.2 billion to subsidize 10,000 or so units of permanent supportive housing. It provides a subsidy of roughly $130,000 per unit, which then is added to, in some cases, state and federal grants, private grants, low-income housing tax credits, and other sources to create a very complicated capital stack to fund the construction of this housing. We’re seeing the pace of this construction really pick up.

At the same time, $130,000 per unit doesn’t even come close to covering the cost of a permanent supportive housing unit. You have the expense of on-site services, and then you have all the attendant costs of building any kind of housing in Los Angeles, which are significant. In addition, the publicly owned sites that we have tended to use for these supportive-housing projects have often not been built on for a reason. Some of them are eccentrically shaped or are steeply graded, or have other complications that add to the cost of construction. They often have been passed over before by public agencies or private developers. That means that that $130,000 subsidy is a fraction of the total per-unit cost. More broadly, more than three-quarters of our residential land is zoned for single-family development. That further restricts where any multi-unit project can go.

SL: Yet despite these challenges, which sound incredibly daunting, L.A. in a lot of ways has—this is not to say that every building is successful—had a lot of success. A lot of very talented architects have been part of the process. New typologies are starting to come into the mix. There seems to be substantial innovation despite all these obstacles.

CH: The response from the architectural community here has been remarkable. The schools—UCLA, USC, SCI-Arc, and Woodbury University especially—and the AIA L.A. chapter have been deeply involved in these questions, which was not the case as recently as five years ago. And the firms here have drawn on the great tradition of innovation in L.A. residential architecture, which has long combined design ambition with economy and pragmatism.

To me, that’s the thread that connects all the best and most important residential architecture in Los Angeles, going back to Craftsman architecture, early Modernist experiments, bungalow courts, the Case Study program, all the way through L.A. School architects like Frank Gehry, Thom Mayne, and others and up to firms working now. This combination of ambition and pragmatism—and an openness to informal, even ad hoc solutions. I think the best of the homeless housing and affordable housing has embraced that tradition.

I have to say, my highest admiration is for the firms that are willing to go through an often-punishing public process, knowing that they’re not going to have control over every detail, that there’s going to be a huge amount of pressure on the budget and the bottom line and the choice of materials and so on.

SL: Let’s talk about some of these innovative designs.

CH: There are projects going back to the 1980s, like those by People Assisting the Homeless (PATH), that established a tradition here of architects applying the full range of their creativity to these challenges. In recent years a long list of L.A. firms have really stepped up. Michael Maltzan, Koning Eizenberg, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects [LOHA], Michael Lehrer, KFA, a number of others. Then occasionally firms based out of town, typically partnering with L.A. firms.

There’s a real flexibility about materiality and construction. There are some sites and some projects where a more traditional wood-frame approach has been the most efficient. And there’s been encouraging progress on prefabrication and modular units. Some of that goes back to projects that Maltzan did for Skid Row Housing Trust that helped us understand when and how modular makes the most sense. We have a number of projects in the pipeline at the moment that are using one kind of modular approach or another.

SL: The theme of our current issue is “Interiors for Everyone.” Creating well-designed interior environments for the entire population sometimes gets overlooked in this type of housing. What makes up good design when you’re building under such difficult conditions? How do you best address daylight, cross-ventilation, green space? What are some of the ways architects here are doing this?

CH: When you’re talking about light, ventilation, circulation, connections between inside and out, the way that a project is positioned on the site, the most experienced residential architects are able to bring the same lessons to publicly funded projects that they would bring to a private house or apartment.

These are things that don’t necessarily have to add much cost. For instance, when you’re dealing with a very quickly built modular project, the quality of circulation space and the landscape becomes crucial. We have the advantage in Los Angeles of being able to have a lot of open-air circulation, and to complement sometimes very efficient interior spaces with more generous outdoor spaces. There are a number of projects that have been very clever in thinking about that.

It also means accommodating tricky sites. The LOHA project Isla Intersections, for instance, which is funded by HHH on city-owned land, thinks carefully about open space and adjusts itself to a difficult site that combines a former traffic island and a rail right-of-way near the intersection of two freeways. Almost any challenge you can imagine a project facing, this one has it.

SL: We’re talking about innovation in process and structure, but maybe we should also talk about procurement, because that seems to be a sticking point with affordable, public, or homeless housing.

CH: There is, on the one hand, the importance of a pre-approved bench of architects to streamline the process, and that’s something that our Bureau of Engineering has been good at creating over the years. I’ve been very encouraged by the number of L.A. firms that have figured out how to work within that system.

In the case of HHH, 10 percent of the total funding was set aside for a separate Innovation RFP seeking creative approaches to financing and construction. We brought together a terrific design panel to assess the entries that included Deborah Weintraub from the Bureau of Engineering, USC dean Milton Curry, and the architects Julie Eizenberg and Sharon Johnston. Of course, the projects were scored in many different categories, but the procurement documents conveyed certain priorities around design.

The first of the funded projects to move forward are three by Studio One Eleven Architects and Daylight Community Development. Their proposals explored lending and financing innovation, and so they were able to get funding in place more quickly than any of the others. The project that got the highest scores across the board in response to the Innovation RFP was a project from Michael Lehrer’s office with a group called Restore Neighborhoods Los Angeles (RNLA). Their proposal was for a relatively modest number of projects on smaller lots in low- and mid-rise neighborhoods that could be a model for replication across the city. It represents an important alternative to the way we’ve been dividing our housing production with the single-family house and maybe an ADU on one end and larger multifamily projects, often on higher-density transit corridors, on the other—and not many options in between, in the so-called Missing Middle.

There’s starting to be some smart thinking about how to layer more affordable housing into low- and mid-rise neighborhoods. The mayor just announced funding for a new Low-Rise Design Lab based in our planning department that will explore effective ways to produce housing at this scale, building on the Low-Rise design challenge we organized last year. Many of the larger goals we talk about—walkability, community, support for local retail, the ability to age in place, enough population density to support transit ridership—are unlocked to a pretty dramatic degree by the ability to live closer together in certain neighborhoods.

The larger point is that there are a lot of causes driving homelessness, but housing precarity, however you define that, is really the most important metric to look at. That has to do with housing prices and with incomes and job stability, but it also has to do with the kind of housing stock that we produce. I think we talk too much about low versus high density, and not enough about flexibility versus rigidity. We need a more flexible approach that can more easily accommodate different ways of living, from multi-generational households to units that can flex to provide workspaces, rental spaces, or even places to quarantine.

The safety net is not just about economics or social services. It’s also about expanding the number of housing options, from affordable units to granny flats, that can catch somebody who’s in a precarious situation before they slip into homelessness. We have under-built housing across L.A. County for about four decades, nearly five now. The pace has picked up quite a bit under this administration. But that backlog is still significant. You combine that with the rise in prices that we have seen, those are all interrelated forces that mean that the housing safety net has been shrinking or fraying.

SL: There’s been some doubt that the goals for HHH, as far as the number of units being built, will eventually be reached.

CH: The goal was to build 10,000 permanent supportive housing units over ten years, and we’re on track to reach that goal. Of the 124 HHH-funded projects, 20 are completed, and another 72 are under construction or fully permitted. Three more have all their funding secured and are waiting for Notice to Proceed. Only 29 remain in the pre-development phase. So, the next two to three years will see a significant wave of completions. We have 39 projects, totaling more than 2,000 permanent supportive units, that’ll open between now and the end of this year alone.

SL: We’ve talked a lot about some great innovations, but what are some ways to get those to be the norm?

CH: There’s not a culture of comprehensive or especially rigorous design review in this city. That’s good and bad. I think a lot of architects would tell you that it’s one of the reasons they have appreciated working in Los Angeles—that freedom. But when it comes to the kind of consistency that you’re talking about, on a typical project, I think there is progress we could make.

Another important part of this is just continuing to feed more talented architects into the system. As more talented architects understand how to work with the city, the quality also begins to build. We’ve seen signs of that happening over the last several years.

SL: Right. I like the way you put that. It’s sort of exponential. Once you have one, then others will be more interested.

CH: We’re already starting to see this. All those offices working on homeless housing had younger associates who worked on those projects, who cut their teeth on them, who understand those processes. When they go off to other firms or start their own, you begin to build an ecosystem of multiple firms that have expertise in this kind of work. And a willingness to do it. I think we’re at the beginning of a virtuous cycle that begins to feed on itself in a positive way, in terms of the number of architects here who have some expertise in doing this kind of work and doing it at a high level.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Products

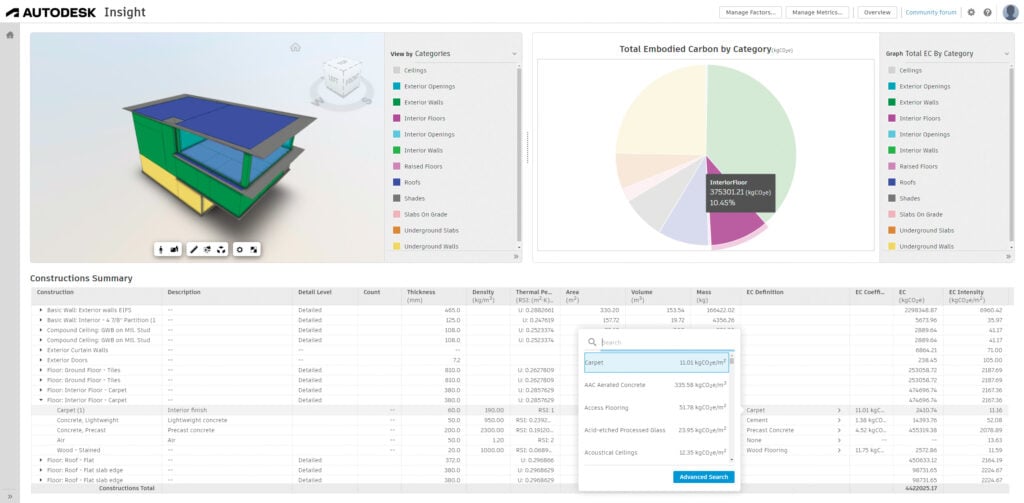

Autodesk’s Forma Gets You Ahead of the Curve on Carbon

Autodesk Forma leverages machine learning for early-phase embodied carbon analysis.

Products

Eight Building Products to Help You Push the Envelope

These solutions for walls, openings, and cladding are each best-in-class in some way—offering environmental benefits, aesthetic choices, and design possibilities like never before.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q3 2024

Policy initiatives are gathering momentum as the federal government and building sector organizations align their expertise under the umbrella of the Inflation Reduction Act.