March 20, 2013

Steven Holl: “If Everybody Else Quits Drawing, It’s Fine With Me”

Steven Hall talks about his watercolor drawings

When we started planning our “creative process” issue, it became obvious that we’d use the opportunity to circle back to Steven Holl, whose watercolors we’ve featured in the past and remain absolutely central to his process. Holl has published two books of watercolors, Written in Water (Lars Müller, 2002) and Scale (Lars Müller, 2012), and loves talking the role they play for him. In fact, the connection between initial drawing and completed building is often remarkably strong. The AIA 2012 Gold Medal-winning architect is an utterly disarming interview (it feels like you’re having drinks with him at a bar instead of conducting a formal inquisition). Our conversation formed the basis for the recent magazine article. An edited version follows:

Martin C. Pedersen: Your watercolors are famous. Are they always the first gesture on a project?

Steven Holl: Yes. And I have thousands of them. Do you know how many watercolors I have?

MCP: I have no idea.

SH: More than 10,000. I have these boxes over my desk. They go all the way back to 1977.

MCP: How did that start?

SH: I have always drawn. Drawing is central to architecture. I used to do pencil drawings. Around 1979 I streamlined it to the five-by-seven watercolors. I decided to fix that format so that I could always have my sketches available.

MCP: Do you draw when you’re traveling?

SH: Yes. Every day. I did three drawings this morning between six and nine. I worked on three different things. I’m working on a big project in Dongguan, China. And yesterday we changed the entire concept. And you know what? A five-by-seven-inch watercolor pad will hold 5.5 million square feet.

MCP: You get up every morning and it’s almost like you get on the treadmill. You’re working out ideas.

SH: No, no, no, it’s more like meditation. The reason it’s better in the morning is your head is clearer. Architecture depends on intuition. You can have a thousand problems in your brain. You put all those things in your head, go to bed, sleep, wake up in the morning, and begin to draw. You don’t read anything. You have it all in your mind. And then your mind and your hand make an intuitive mark on the page. That’s the beginning of a concept, for a huge project.

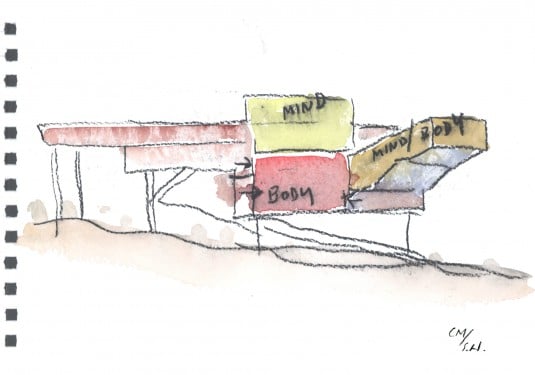

Body and Mind

MCP: This reminds me of Ernest Hemingway. He’d get to a point where he knew what was happening next, then stop, and sleep on it. Graham Greene did something similar.

SH: In the morning, you’re closer to the dream state. If nobody interrupts you, you can go straight to the drawing board. I take a shower of course, but I don’t eat breakfast. I don’t do anything else. I never look at the newspaper in the morning. That’s the worst thing you can do with your brain. I look at the news at night. I don’t take any phone calls in the morning. And I don’t have any power breakfasts. Never do that. When I first came to New York in 1977, a friend said , “Steven, power breakfasts are a New York tradition. You’ve gotta meet the people who’re going to be clients.” I never took his advice.

MCP: Do you draw to solve problems, or to explore ideas?

SH: All of those things. Play is central. Le Corbusier said, when you’re making designs, you need to play. It’s central to the intuition. Imagination needs to be free. It can’t be fettered by all these programmatic things. You need to be free to play.

MCP: Drawing is central to your creative process. Do you worry that it’s going away?

SH: I don’t care what everybody else does. We just won the extension to the Kennedy Center. We beat Diller Scofidio, Richard Meier, Rafael Vinoly. It was a hundred firms on the first list and then came down to four. We won. And guess what? All the concept drawings were made by watercolor on five by seven. So if everybody else quits drawing, it’s fine with me.

MCP: Do you encourage younger architects to draw?

SH: Of course, of course. My students are going to understand what to do. In the digital age, we’re losing things. It’s just like medieval times. The Romans knew concrete. They built the Coliseum. But we lost it for a thousand years. We’re in the Middle Ages now, and we’re losing things.

MCP: When do the watercolors make the leap to the next step?

SH: Immediately. I’ve sent them by iPhone from an airport in Korea.

MCP: You’ll just take a photo?

SH: Sure. When we got the digital technology, I could supercharge this process. It’s my secret weapon. We did the competition for an extension of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and I had to go to China. I also had a presentation in Korea. The competition was due, right? And I didn’t like our scheme. I woke up one morning, in Beijing, and drew a new one—totally different—on two five by seven watercolor pads. I was on my way to Korea and put the pad on the table, with a light on it, and I snapped the iPhone image, and sent the drawing to New York. When I arrived home, there was a model. So they go from my watercolor directly into a 3D computer drawing. That drawing goes into our 3D printer and in a matter of, say, twelve hours, in the time that I’m flying, I can have a model waiting for me when I arrive back at the office.

MCP: Do you draw details?

SH: I sketch out details, of course. Door handles, light fixtures, everything.

MCP: Is everything sketched?

SH: Everything I’m designing. How else are you going to do it? People wonder how I can do so many details. I don’t draw the detail drawings. I just do a sketch of the concept. You look at our projects. Go and look at the sports center at Columbia University. When you go up there and see the details, like that special linear guardrail that picks up the sunlight in different ways, I drew that in watercolor.

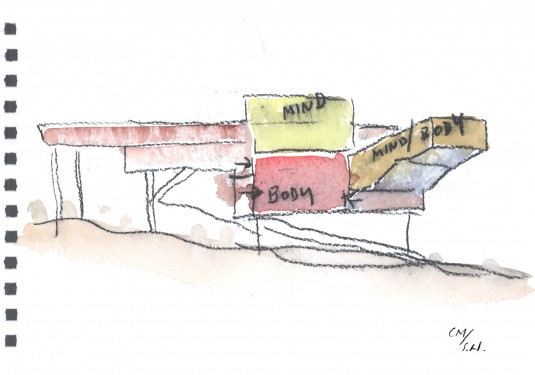

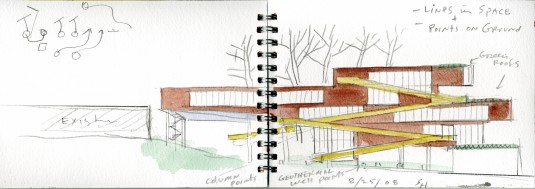

Sketch for the design for a sports center at Columbia University

MCP: How many drawings did you do for that project?

SH: That one took a lot, because we had several schemes that I had to keep revising.

MCP: I’m guessing that you did a number of concept drawings but then once you settled on a final idea you did several detail drawings throughout the building.

SH: Sure, sure. There were probably fifty.

MCP: So for the larger projects, there might have as many as a hundred drawings?

SH: Yes. You know, I bet it’s not fifty for Columbia. I’d say more like thirty-five. I think Linked Hybrid was probably a hundred. I don’t always draw on five by seven.

MCP: So if the project gets bigger, the scale of the watercolor gets a little bigger?

SH: Yes. Today I worked on Dongguan. I redid the concept on five by seven. The basic idea is a new collection of building types that fuse landscape and architecture. After that, I drew the whole plan on a bigger format, at one-to-one-thousand. But that was also a watercolor, eighteen-by-twenty-four. I use a watercolor pad by Fabriano. I’m using the same technique, charcoal, watercolor wash. But when you’re doing a big project, and there’s six different building types and all these different program parts and pieces, you need color to tell you where the residential is, where the landscape is.

MCP: Are there people in your office responsible for taking your drawings and putting them into digital form?

SH: There are six people working on this team. It’s a huge project. They scan it and then email it to everybody. The process today is super charged, because of the digital way that everything connects.

MCP: How do you crit the concept once it’s off the sketchpad?

SH: There’s a model built, and we have pinups.

MCP: Are there interstitial drawings along the way?

SH: They’re all digital. We started using computers in 1992. We had a single computer. If you look at the drawings for the Kiasma Museum in Helsinki, the final ones were a combination of watercolors and computer drawings. In that case, we scanned the watercolors into the presentation, and they were printed on the same boards, with the computer drawings. That building is very sophisticated in three dimensions. It has a doubly warped curve that’s holding the whole thing up. I don’t think we could’ve done that without digital.

MCP: The computer must have been the size of a room.

SH: It wasn’t that big. But it was a clumsy thing. And we had only one! We had to work on it twenty-four-seven. People would come in and spell someone off the machine, and another guy would get on it. I had three people in my office in 1993.

MCP: How many do you have now?

SH: A little bit over 40. I’m not going to get bigger than 44. I made that as a New Year’s resolution. Because I went up to 64 once, and it was a nasty managerial problem. I am an architect atelier. Architecture is an art. For me it’s not a corporate activity. I don’t like corporate architecture.

MCP: The drawing must be a way to hold onto that atelier feeling.

SH: Of course, of course, because I’m doing the design. I’m not saying I do it alone. Everybody critiques me. My partner is a genius. He knows how a program should work. Chris McVoy is key in this process. As are many other people. Filipe Taboada is a genius. Garrick Ambrose is a genius. I have geniuses here. And I’ll tell you how I did that. I teach at Columbia. It’s very hard to get into Columbia, right? I’m going up to my class today. I have twelve students. They didn’t have an easy time, first of all, getting into the architecture program. And then they don’t have an easy time getting to my studio. They have a lottery to get in. So I’m looking at twelve students right now. I have their names. And I will hire the best one to come into my office in May, when the term is over. I do that every year.