October 29, 2012

Stoking the Furness

Philadelphia played a large role in ushering in an age of modernism, and architect Frank Furness was a major part of the movement.

Frank Furness, Architect Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), 1876 Photo: Gutekunst Descendents of Frank Furness, the great 19th century Philadelphia architect, were emphatic. It’s not pronounced Fur-Ness, it’s Furness as in “furnace”. No matter how you say it Furness sometimes “can’t get no respect.” During his lifetime he completed some 1,000 projects yet too many of those distinctive works were callously demolished by his own hometown. The glorious Victorian interiors of the PAFA building were once covered in sheet-rock during the 20th century.

A glimpse of PAFA’s hand crafted Victorian interior

Photo: Joseph G. Brin © 2012

Is anyone stoking the furnace of his reputation in the 21st century? George E. Thomas, cultural historian and author, met with Harry Philbrick, director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art (PAFA), an unabashed enthusiast of architecture. They conspired to pull off Thomas’ idea of a citywide celebration this year – “Furness 2012 Inventing Modern” — with exhibits and events fanned out to Philadelphia cultural venues and onto the web. You now have a rare, multifaceted view of an architect who embodied the essence of 19th century Philadelphia, and is considered a linchpin in the evolution of American modernism.

Philadelphia Hall of Famers: Frank Furness, Architect – drawings c. 1881 (foreground) Thomas Eakins, Painter – “The Gross Clinic” 1875 (rear left) Charles Wilson Peale, Painter – “The Artist in His Museum” 1822 (rear right)

Photo: Joseph G. Brin © 2012

Detail of the front elevation of PAFA

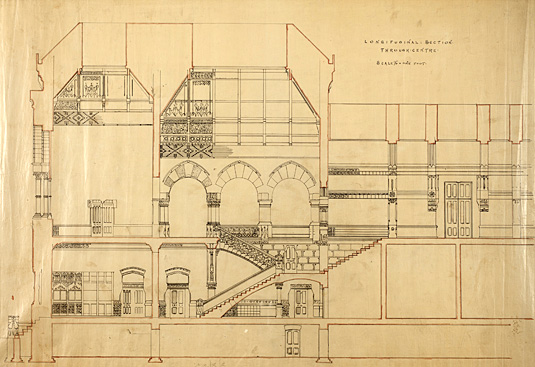

Anchoring the centenary celebration is “Building a Masterpiece: Frank Furness’ Factory for Art,” a promising and accurate exhibit title. But, somehow, I was expecting more fireworks. As it stands, the “Factory” show (located in the architect’s PAFA building) rewards those who read the exhibition notes carefully and, more to the point, already know how to read architectural plans. You come away with a rich, visceral appreciation of the PAFA building as a supremely collaborative effort. Though the building and drawings may speak for themselves, more visual analysis would have helped broaden lay audience understanding and appreciation of Furness’ important contributions. When a lively group of school children swept past the exhibit in the main hall into an adjacent painting gallery I wondered if their guide just assumed that the students were too young to understand the Furness drawings. Photographs of machine parts, factories, natural forms, and other details that Furness drew inspiration from, or even an interactive spatial model, might have caught their eye.

Drawings unadorned (in Mylar sleeves) bring you close to the design process of Furness & Hewitt. George Thomas says these were working drawings, “instruments of service not precious art objects”

Photo: Joseph G. Brin © 2012

The show boasts 34 impressive drawings, many of which have never been publicly displayed before. Yet I still had anticipated a stronger visual explication of historian Thomas’ breakthrough thesis on the connection of Furness’ work to the industrial milieu of 19th century Philadelphia, and factories in particular. The genesis of his grammar of machine expressionism could be charted graphically just as Louis Sullivan’s organic forms were sequenced in his extraordinary pencil drawings from seed to full flowering. Sullivan, who worked briefly in the Furness & Hewitt office, said Furness “made buildings out of his head.”

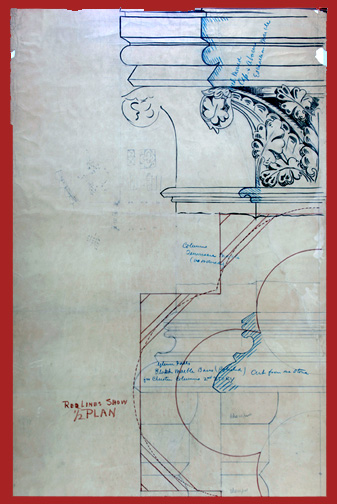

Stone Craftsman’s “shop drawing”

Nonetheless, the drawings are a treat to see – the detail, the handwork, the scattered notes of a major building in the works. Very large and rough shop drawings, presumably from stone craftsmen interpreting the architect’s intentions, reveal the shorthand construction language that accomplished the stunningly detailed PAFA building. In some drawings, every single patterned brick is shown in ink or pencil. In other cases, a broad suggestion of material and form in chalk sufficed. Engineering drawings also on display reveal the essential “bones” of the building.

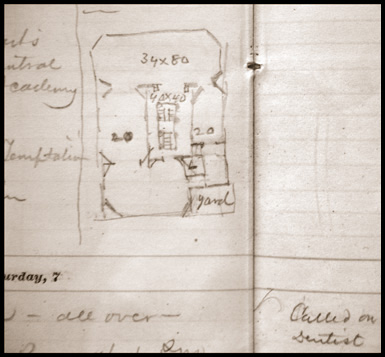

Diary: Addison Hutton, Architect

Photo: Joseph G. Brin © 2012

Most surprising and poignant is the inclusion of the diary of Addison Hutton, a successful architect invited to enter the PAFA competition that Furness and his partner Hewitt ultimately won. In October 1871, Hutton’s diary entries show a tiny plan sketch of his proposal and reminder of a dentist appointment. “Conflict of interest,” as we know it today, had not been invented yet in the 19th century so the PAFA building committee was comprised of people, including Furness’ brother-in-law, openly pulling for competing firms. “Building a Masterpiece: Frank Furness’ Factory for Art” peels away layers of art, technology, and history bringing the whole process to life, from the foundation drawings on up. The exhibit affirms that Furness’ exuberant flights of polychromatic ornamentation were integral to a muscular, powerful massing that was both structurally sophisticated and forward thinking technologically. A whole confluence of cultural forces reached physical form in this path-breaking art museum beginning with local titans of manufacturing and business who sat on the building committee. As exhibition materials state, the PAFA design “combined a traditional palace-like front facade with a factory like extension…a new building type that looked to the future…Frank Furness brought the insights of engineering and the power of the machine age to architecture.” His strategic use of light addressed the specific needs of both galleries and studios implementing structural feats for optimum results. This organic link between Furness’ architecture and the industrial culture that formed his clientele served him as the quintessential Philadelphia architect, inextricably linked to his city.

Drafting tools of the era and type used in the Furness & Hewitt office

Photo: Joseph G. Brin © 2012

Frank Furness is not the only historical Philadelphia architect of note, but he gets under your skin. You can’t help being captivated by buildings that are a feast for the eyes, invite your touch, and take a bold stand.

Section drawing of PAFA

“Furness 2012 Inventing Modern” reminds us that despite the many silly architectural taboos that have come and gone (“no” history, “no” ornament, “no” color…) the fiery Furness would have had none of it. Whatever worked he used. Whether it was a metal gate patterned on a delicate tree leaf, a bronze baluster wittily quoting shiny components of a new steam engine or a massive steel truss spanning an exhilarating “loft” space, Frank Furness, Architect, wielded his great skill with a forceful personality. He embraced his times head on.

Joseph G. Brin is an architect, fine artist and writer based in Philadelphia, PA.