January 7, 2014

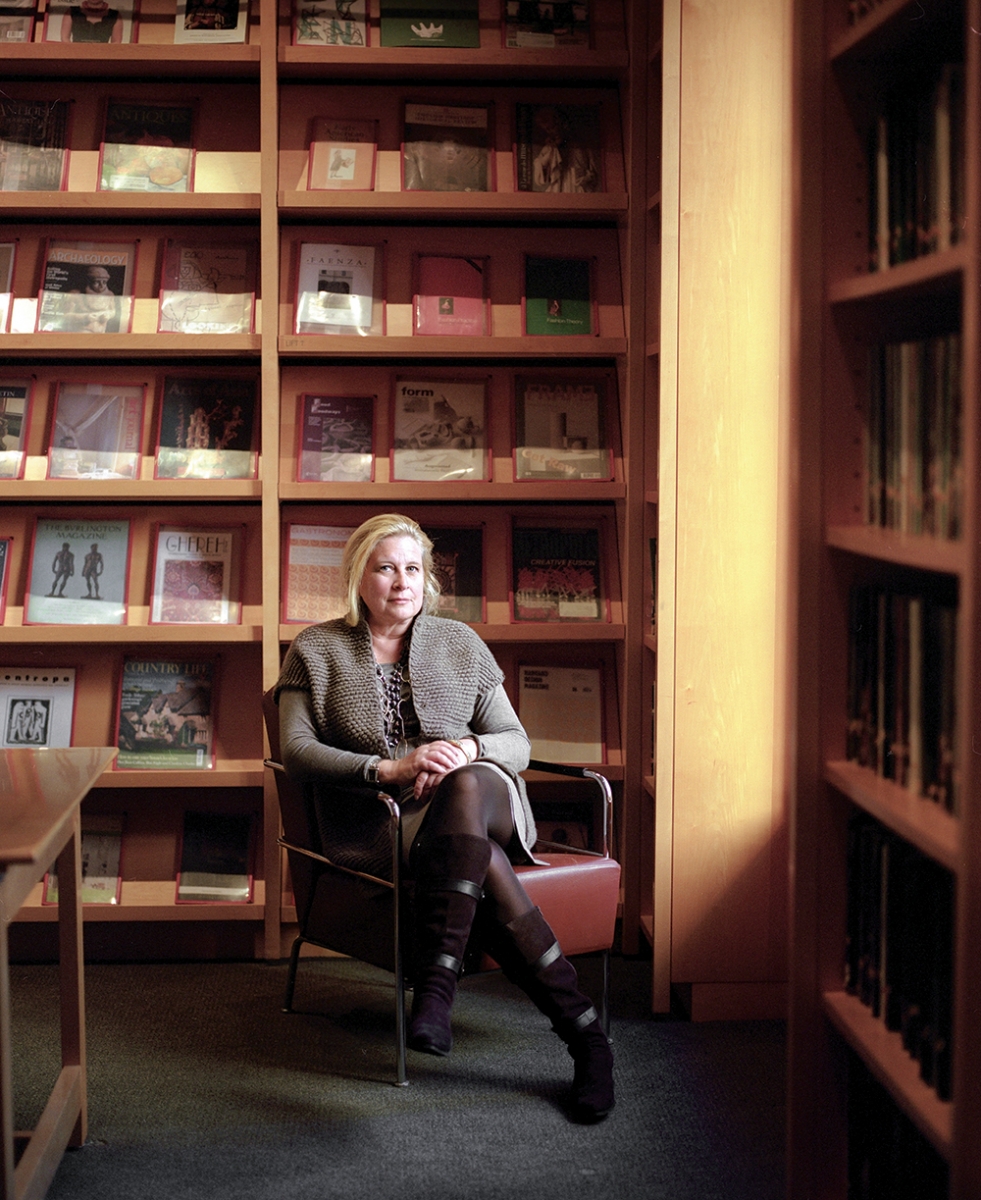

The Renaissance Woman at the Helm of Bard’s Graduate Center

An educator and historian who has elevated the study of material culture, design history, and curatorial practice to fresh levels of depth and understanding.

Photography Soohang Lee

Weber is an art historian, curator, antiques dealer, documentary filmmaker, professor, and, with the establishment of BGC in 1993, a director of uncommon expansiveness who has elevated the study of material culture, design, and curatorial practice to that of a fine art. Material culture was marginal in 1992. Only two graduate programs existed in the United States: One was the Winterthur program at the University of Delaware, with its American focus, and the other was the newly formed Cooper-Hewitt’s National Design Museum program, where Weber was among the first to earn a master’s degree. Twenty years later, BGC is an internationally respected institute that trains curators and collaborates on exhibitions for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), and other leading institutions.

I meet the ebullient iconoclast at the BGC Gallery. William Kent is the organization’s most ambitious show to date, an exhibition ten years in the making. Weber stands under an oil portrait of Kent, an artist who transformed English taste in the early 1700s with his architecture, interiors, furniture, metalwork, illustrations, costumes, and gardens. Despite his enormous influence, he died in obscurity in 1748. Few English curators would touch Kent because his creations are scattered, difficult to authenticate, and would require negotiating 40 to 50 separate loans. Plus, no Kent archive exists. These challenges drew Weber to him. “This is my strangeness,” she says. “I always like to study areas no one has any interest in.”

The BGC’s latest exhibition, curated by Susan Weber and Julius Bryant, is its most ambitious to date. Born out of a ten-year process involving a scientific committee of British scholars and a close collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the show takes an in-depth look at Kent’s genius through nearly 200 works spanning four decades.

The BGC’s latest exhibition William Kent: Designing Georgian Britain, curated by Susan Weber and Julius Bryant, is its most ambitious to date. Born out of a ten-year process involving a scientific committee of British scholars and a close collaboration with the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the show takes an in-depth look at Kent’s genius through nearly 200 works spanning four decades.

When asked to point out a favorite “Kentian” item, her blue eyes flash and she races up the elegant central staircase and stands before a gilt settee Kent designed in 1730 for Wanstead House, Essex. The piece is a visual feast, elegantly embellished with ancient motifs (sphinxes, acanthus scrolls, a mask of a woman—possibly Roman goddess of the hunt, Diana), scrolled elbows, and festoons of flowers, upholstered in opulent Genoa velvet (faded from an original crimson that might have matched Weber’s pedicure). “This stuff was very exotic,” she explains. “This stuff is like stage scenery. England is the country of boring brown wood. This is gilded! What’s also fun about Kent is that he has humble beginnings. This is a rags-to-riches story.”

How it got to West 86th Street is something of a rags-to-riches story as well, and it captures the demands and rewards of doing work other institutions won’t touch. Namely, after nine years of securing loaned objects and the catalog going to press, an English lender pulled out of the show, denying the exhibition the promised settee and other items. A tip-off from Yale University Press, BGC’s longtime publisher, led them to the UK’s National Trust, which told Weber where to find an identical Kent settee from 1730 (only eight exist and six were unavailable). “They’ve been sitting outside on a covered porch at a National Trust house,” she says “They don’t know what they have! I send a friend. He says they’re authentic. He takes hundreds of pictures and goes to Wilton to compare with the other six. They get the settee conserved and send it to us.”

The Kent exhibition is the first major show to examine one of the most influential designers of eighteenth-century Britain. Seen here, William Hogarth’s “The Assembly of Wanstead House” (1728-31), which is set in the ballroom believed to have been designed by Kent.

She points to a painting in the gallery directly above the settee and says, “This is the document that tells us that it was at Wanstead, and we have the sales record.” (Using paintings as historic documents to explain culture is a scholarly practice at which BGC excels.) Beaming and breathless, she remarks: “That is how a piece re-enters the scholarly world, and a whole new life is rediscovered.”

Weber readily acknowledges that she and BGC didn’t get where they are today themselves. Bard College’s president, Leon Botstein, and BGC Gallery Director Nina Stritzler-Levine have been integral members of Weber’s team since 1992. Academic Dean Peter Miller expands that vision today. If the Met is a metropolis with a vast permanent collection for curators to use in shows, BGC is a kunsthalle dependent entirely on complicated loans. Nevertheless, BGC’s exhibits are meticulously conceived and staged. Cast Iron elevated a base metal to a fine art; Women Designers unearthed and displayed work of ruefully little-known twentieth-century designers. BGC catalogs are gorgeous, scholarly tomes. Paola Antonelli, MoMA’s Senior Curator, Architecture and Design, says, “When you look at how much serious, deep work the BGC has initiated and completed in the past 20 years, it feels like the institution is as old as MoMA, the Cooper-Hewitt, and the Victoria and Albert combined.”

Upstairs in her fifth-floor office, Weber reclines on a sleek gray sofa that is as simple as Kent’s settee is opulent. On a small round table rests a wine glass full of Coca-Cola. “Yes, I drink Coke!” she says, smiling.

“If I had stopped to think about it, I wouldn’t have done it,” she says of the 20-year journey. A native New Yorker, Weber attended private school in Brooklyn. Her father manufactured shoe trees and shoe polish and other shoe items; her mother was a collector who took Weber hunting for antique European porcelain. Her “Rosebud” object was a reproduction Queen Anne dollhouse that she knit rugs for and renovate —until she was twelve and saw a better one at the Smithsonian.

After earning an art history degree from Barnard College–Columbia University in 1977, she worked for the Albany Museum and then produced two art documentaries. She started the art journal, Source: Notes in the History of Art, published by the Ars Brevis Foundation. In the 1980s, she enrolled in Parsons’s first decorative arts master’s program at the Cooper-Hewitt, where she wrote her thesis on the painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler—as a decorative artist. In 1998, she completed her doctorate at the Royal College of Art in London.

Weber was married to Hungarian-born hedge fund billionaire George Soros for 20 years, and she still hates the fact that when she started BGC his name was always mentioned as the reason for her success. But institutions like BGC do not exist without endowments, and Weber thanks Soros for establishing the Iris Foundation, which granted Bard the millions Weber used to buy the town house, hire faculty, and start the library. Twenty-three students enrolled the first year; tuition was $17,000 and the library had 17,000 volumes. Today, BGC boasts a staff of 90 and 50,000 volumes, and tuition is $60,000 for two years (though 85 percent of students receive financial aid).

Weber and Soros married in 1983, when she was 28 and a partner in an antiques store, and divorced when she was 48. In the years between, they bought a small house in South Kensington near the V&A and started the Open Society Fund, granting money for exhibits and fellowships in Eastern Europe. “I ran the foundation for many years,” she says. “We had two children. We were traveling all over the place. Then I decided it wasn’t rewarding enough just to write the checks for other people’s projects. I applied for a job at the Cooper-Hewitt. They interviewed me for a year and a half. I would have restructured their program. Later, I learned that they thought I was too independent a thinker.”

Currently on view at the BGC, this groundbreaking exhibition documents the search for a distinctly “American” aesthetic in textiles and fashion, through World War I and the subsequent years. This quest was spearheaded by the American Museum of Natural History, which allowed designers unprecedented access to its collections of Native American, Mesoamerican, Andean, and South American objects.

People figured Weber would hire others to do the heavy academic lifting. “Billionairess Snubbed by Cooper-Hewitt, Soros Opens Furniture School of Her Own” ran a headline in the New York Observer. Botstein disagreed: “In America, there’s a long tradition of the gentleman scholar…but if a woman does it, it’s somehow suspicious.” With a 15-page outline of a new academic program, Weber decided to establish her own institute devoted to the decorative arts. A trustee at Bard, she approached Botstein, who was known for his innovative approach to education and the arts; he loved the idea of a satellite campus devoted to material culture and became intimately involved in its operations. (Last year, in fact, he wrote an essay on circus music for BGC’s exhibit, “The American Circus.” Weber’s own essay, “The WPA Circus in New York,” is almost Lou Reed–like in its depiction of a 1930s underworld inhabited by clowns named Shorty, Lollipop, Salt Pork, and La-La, “the happy poet of pantomime.”)

Nina Stritzler-Levine recalls the risk they undertook, working from a temporary space on Madison Avenue and 67th Street: “We had no collection, no loans, no reputation, no gallery furniture, no equipment of any kind, and no program. But there was a vision that this newly forming graduate program devoted to the decorative arts would have a gallery.”

Fifty-seven exhibits later, Weber stands before a crowded symposium entitled, The BGC at 20. In a four-minute talk, she conveys two decades of insight: “Twenty years is a long time in a person’s life, but in an institution it’s a very small amount of time.” Then she surprises an audience used to her innovations by unveiling History of Design: Decorative Arts and Material Culture, 1400–2000, a comprehensive and beautiful textbook ten years in the making. She declares her hope and goal that this book would be to material culture what Janson’s History of Art was to survey courses when she was in college.

The catalog for Weber’s most recent accomplishment, William Kent: Designing Georgian Britain, quotes a warning that the British art historian Horace Walpole issued in a letter announcing Kent’s death: “…scarce any school retains its purity after the death of the institutor.” Weber is determined that Walpole’s admonition not prove true in her case. “I want to make sure this place is strong for its future,” she says. “I want the place to carry on when I am no longer on the earth.”

A visual glossary of the Bard Graduate Center’s largest exhibitions

All images courtesy the Bard Graduate Center

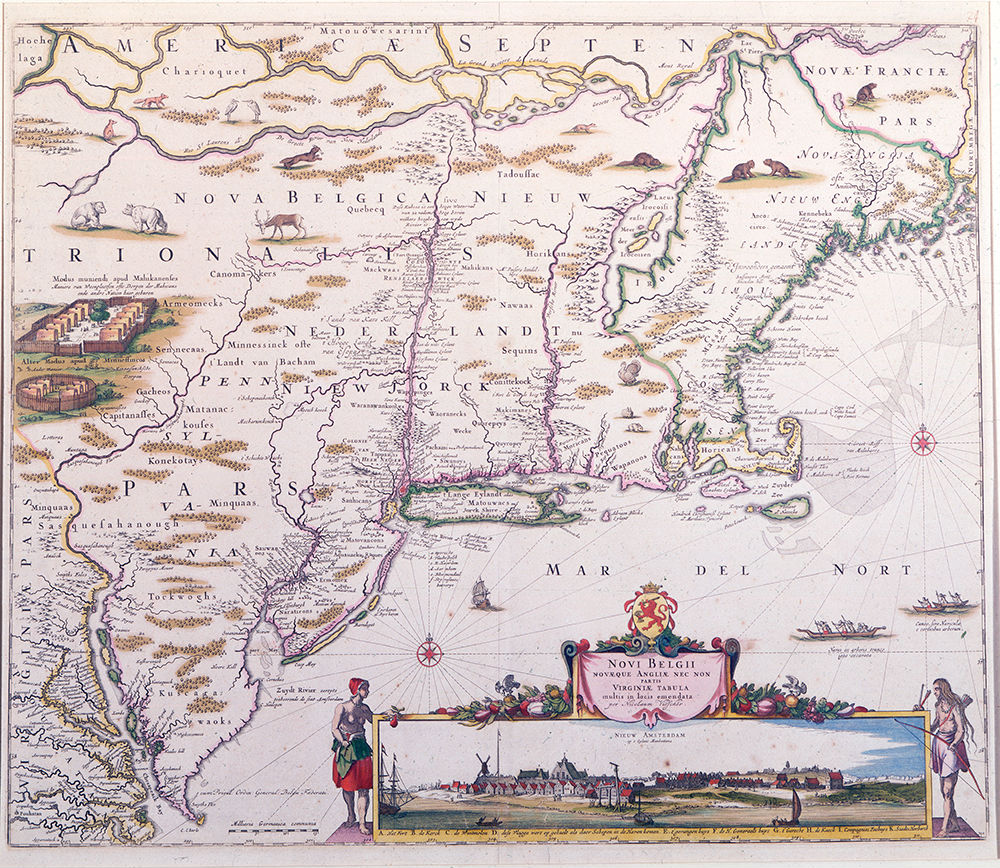

Exhibition: Dutch New York between East and West: The World of Margrieta van Varick

Year: 2009–2010

The BGC used the possessions of one woman and her family in the late seventeenth century to celebrate the lasting legacy of Dutch culture in New York. Intertwining art, history, and the decorative arts, this fascinating show did not get the critical reception it deserved. Pictured: Novi Belgii Novaque Angliae Nec Non Partis Virginiae Tabula, ca. 1655-77, a hand-colored engraving by Claes Janzoon Visscher.

|

Exhibition: Women Designers in the USA, 1900–2000: Diversity and Difference Year: 2000–2001 BGC’s new millennium project was the first survey of female American designers and how they helped shape the twentieth century. Curated by Pat Kirkham, the exhibition was a “landmark in research and scholarship, and grounded in feminist studies,” says Stritzler-Levine. |

|

Exhibition: E.W. Godwin: Aesthetic Movement Architecture and Design Year: 1999–2000 The exhibition and accompanying book looked at one of the seminal figures in ninteenth-century English architecture and design. |

Exhibition: A.W.N Pugin: Master of Gothic Revival

Year: 1995–1996

In the early years, the BGC became adept at “Bardizing” existing projects, expanding their scope and depth. This exhibition on the nineteenth-century British designer was adapted from London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, with a catalog that established the BGC’s longterm collaboration with Yale University Press.

|

Exhibition: Cast Iron from Central Europe, 1800–1850

|

|

Exhibition Sheila Hicks: Weaving as Metaphor Year: 2006“This was our first exhibition on a living artist,” says Stritzler-Levine, who curated the show as a deep dive into understanding Hicks’s creative process and constant innovation with materials. The catalog, which designer Irma Boom calls her “manifesto,” won the Gold Medal for “The Most Beautiful Book in the World” at the Leipzig Book Fair. |

Exhibition along the Royal Yoad: Berlin and Potsdam in KPM Porcelain Painting, 1815–1848

Year: 1993–1994

The first exhibition at BGC used the work of Carl Daniel Freydank, who painted views of Berlin and Potsdam on porcelain between 1838 and 1848, to explore how Prussian culture transformed during that era. In a bold move, the curators engaged a photographer, Bruce White, to shoot those same views after the Berlin Wall came down, offering a full trajectory of how the city has been portrayed through the ages.

|

Exhibition: Objects of Exchange: Social and Material Transformation of the Late Nineteenth-Century Northwest Coast Year: 2011Using a range of goods created by indigenous peoples of the American Northwest, curator Aaron Glass, BGC students, and specialists suggested that the turn of the century doesn’t mark the end of “traditional” art and culture, but the dawn of modernity in indigenous society. This was the first exhibition at the BGC Focus Gallery. Pictured: Mask attributed to sdiihldaa/Simeon Stilthda (c. 1799-1889), Haida. |

|

Exhibition Knoll Textiles: 1945–2010 With never-before-seen archival material, and a close examination of the personalities who influenced the design of midcentury fabrics, this exhibition was the first to showcase the textiles division of the design giant Knoll. Paul Makovsky, Metropolis’s editorial director, was one of the curators. |

Exhibition: An American Style: Global Sources for New York Textile and Fashion Design, 1915–1928

Year: 2013–2014