October 31, 2013

Why the Solar Decathlon Should Enter the Real World

Is the Department of Energy’s well-intended program limited to the buzz it produces?

This article, by Guy Horton, originally appeared on ArchDaily as “The Indicator: Why the Solar Decathlon Should Enter the Real World”.

I don’t mean to poo poo the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Solar Decathlon project, but the more I hear about it the more I wonder if this isn’t an indication of just how far behind the United States is in terms of energy policy and the design of smart environments. Are we really that far behind that we need a program like this to prove this stuff really works? Are people still disbelieving? Do they really need demonstration homes to show how photovoltaics (PVs) produce electricity or how sustainable principles can be applied to architecture? I suppose it makes sense in a country that still obsesses about the Case Study Houses and has debates about whether climate change is a reality.

The purpose of the Solar Decathlon is primarily to educate the public on high-performance building practices. Since 2002 when the DOE held the first one, it’s been putting “green” building in front of people who otherwise would not get to experience it—or, in reality, a self-selecting population of people who are probably already into such things.

The University of Maryland’s entry, WaterShed, which placed first overall, in the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon 2011 in Washington, D.C., Friday, Sept. 30, 2011.

Courtesy © Stefano Paltera/U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

Of course, the other purpose is to get a bunch of architecture students to design and build to gain some practical experience with energy-efficient buildings. The Solar Decathlon has, according to their URL, “Affected the lives of nearly 17,000 collegiate participants.” Undoubtedly, the program serves as a catalyst for young architects-to-be and contributes to the knowledge base of participating architecture programs. How can this be bad?

But does it do anything else? It certainly generates a lot of buzz. But is that buzz that is reaching “tens of millions of people,” as their website claims, having an impact on the mainstream? By setting what are ostensibly mobile homes up in a field, this time in Irvine, California, does it really promote sustainable building practices in a meaningful way?

A little context: I recently returned from a trip to Hamburg, Germany where, even though it can be cloudy a lot of the time, solar power is a fact of life and part of the overall energy picture. People there don’t blink when you bring up PV panels or district solar hot water generation or any number of renewable energy strategies. Solar is simply viewed as part of a comprehensive long-term vision for the city’s energy future. They even believe climate change is real! What a strange land, this Germany.

Now, I think it’s a good thing the DOE is holding these competitions, but I wonder if it wouldn’t be more constructive at this point (this is the sixth event) to get this out of the grassy fields and into the hearts of cities, by partnering with real developers to create real-life affordable multi-family housing, say, in a place where real people need it.

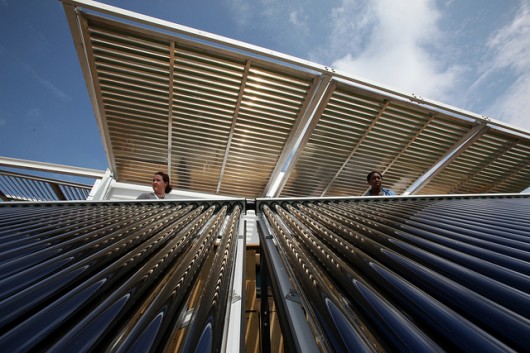

Brianna Bacon, right, and Lizzie DeLeonibus, left, of Maryland look out over Florida International University’s solar thermal collector system at West Potomac Park in Washington, D.C., Wed., Sept. 28, 2011.

Courtesy © Stefano Paltera/U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

In Hamburg, public-private partnerships were formed to convert existing low-performance housing to smart, high-performance housing. One of Europe’s largest energy companies, Vattenfall, worked with a test group to bring renewable energy (a combination of wind, solar, geothermal, and other sources) to converted flats by employing smart metering and smart grid technology. In fact, they completely re-conceptualized the mode of power distribution/consumption and now envision this new “smart” system as the future of energy use for the city—along with hydrogen buses and electric vehicle infrastructure.

It’s extremely ambitious, and, as an American, I found myself being skeptical. Can they really do this, I wondered. The test group customers have to undergo behavior modification and be re-educated about how to consume less energy and use it more efficiently by following the ebb and flow of renewable power sources. Of course, the smart-grid does much of this for them if they go along with it.

Interior architectural photograph of Middlebury College’s entry in the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon 2011, Washington D.C., Sept. 23, 2011.

Courtesy © Jim Tetro/U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

This seems to be the one crucial element of the sustainable equation that often gets overlooked by energy-hungry Americans. People seem to expect that they can consume at the same levels they always have and that houses like Solar Decathlon houses can be experienced the same way they would experience a conventional energy-hog home. It’s set up as if the home has to prove its worth to the customer rather than the customer having to adapt to the home. This establishes a false precedent that, in the long run, undermines sustainable building initiatives.

The other issue is that the Solar Decathlon positions these “experiments” outside the complete context of urban transportation, real neighborhoods, and the overall infrastructure of daily life that would actually “demonstrate” that such homes work.

Team Alberta: University of Calgary’s Solar Decathlon 2013 House Rendering.

Courtesy U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

What if the next Solar Decathlon were in Detroit or New Orleans, or even a Native American reservation out in the middle of nowhere? What if it implicated real energy-users and real buildings? Then it would start to get interesting. Until it does something on this scale it will continue to be temporary, like an event at a World’s Fair or a carnival ride—it will still be something people can question and think of in terms of being outside the norm. The enduring influence of the Case Study Houses, after all, is due to the fact that they are real houses in real contexts, hooked into the grid.

DOE could move beyond the “temporary pavilion” or “demonstration model” approach and actually implement sustainable practices to retrofit existing buildings to have an impact on real communities. This would begin to move their education initiative more into the public realm. By modeling real-world energy initiatives like those found in Hamburg, DOE could increase the real-world relevance of the Solar Decathlon for the future. And if the Decathlon did that, then it could truly consider itself sustainable – in all senses of the word.

Southern California Institute of Architecture and California Institute of Technology’s Solar Decathlon 2013 House Rendering.

Courtesy U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon

Guy Horton is a writer based in Los Angeles. In addition to authoring “The Indicator,” he is a frequent contributor to The Architect’s Newspaper, Metropolis Magazine, The Atlantic Cities, and The Huffington Post. He has also written for Architectural Record, GOOD Magazine, and Architect Magazine. You can hear Guy on the radio and podcast as guest host for the show DnA: Design & Architecture on 89.9 FM KCRW out of Los Angeles. Follow Guy on Twitter @GuyHorton.