May 24, 2021

The Newest Addition to Harvard University’s Campus Is a Paragon of Sustainability

Behnisch Architekten’s design of a new hub for lab research marks a new chapter of sustainable construction and campus planning.

For its largest and most consequential building in a generation, Harvard University has pulled out all the stops to ensure its new Science and Engineering Complex (SEC), located on its emerging campus in Boston’s Allston neighborhood, is a paragon of building health and sustainability.

“Harvard said, ‘The goal here should be the healthiest building at Harvard if not the entire academic world. Period,’ ” recalls Matt Noblett, a partner at the Boston office of German-based firm Behnisch Architekten, which designed the project.

The building was just completed, and its accolades already read like an alphabet soup of ecological distinction: LEED Platinum, and notably the largest building certified under the International Living Future Institute’s Living Building Challenge (LBC). The criteria for certification include seven sections, known as “Petals”: Place, Water, Energy, Health + Happiness, Materials, Equity, and Beauty. There is an emphasis on eschewing so-called “Red List” toxic chemicals.

“This certification brings attention to the fact that only 10 to 15 percent of 80,000 chemicals in industrial use today have any health data; only 9 percent are regulated at a federal level,” says Heather Henriksen, Harvard’s chief sustainability officer. “For the SEC, we purchased 1,700 products that match both Harvard and LBC criteria.”

Elsie Sunderland, professor of environmental chemistry at Harvard’s Schools of Engineering and Public Health and Harvard Healthier Building Materials Academy adviser, adds: “Previously, there was a lack of transparency in the use of chemicals. At the SEC and elsewhere, Harvard is a living laboratory of clean building challenges.”

In addition to its use of “clean chemicals,” the SEC is significant because it is the first major academic building on the Allston campus, and will house the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Architecturally, it expresses both this urbanistic importance and the varied research taking place within.

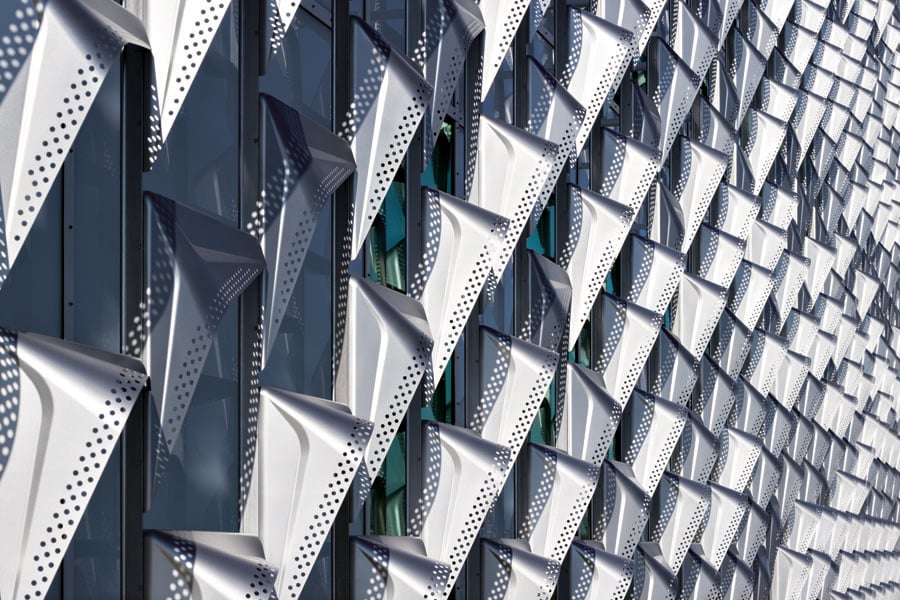

“Along the Western Avenue facade, it is three floating boxes,” says Stefan Behnisch, founding partner at Behnisch Architekten. “This cuts down the massing and makes it like three siblings.” On the opposite side, he continues, the building massing steps down in deference to the nearby residential neighborhood. Lacking Behnisch’s distinctive multi-angled forms, the 544,000-square-foot building is sheathed in a stainless-steel scrim, whose patterning is different on almost every facade.

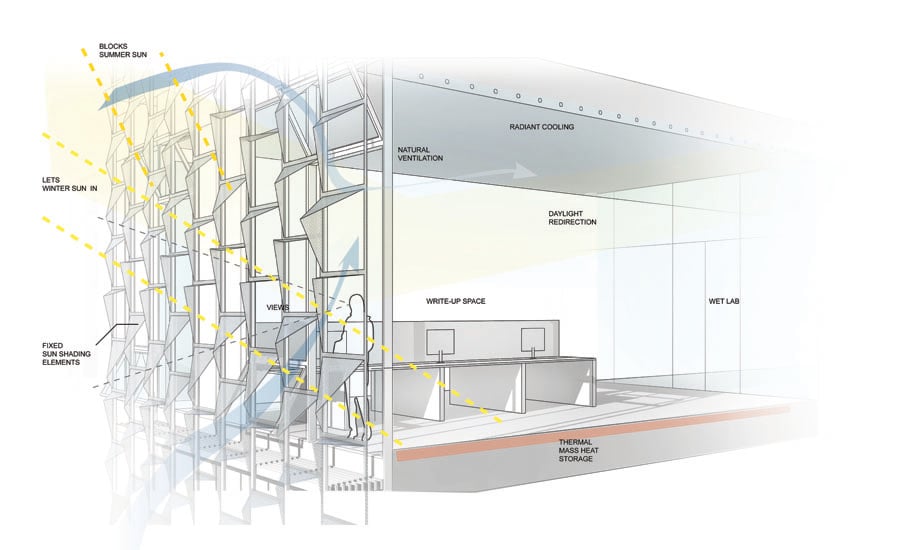

“From a distance, it looks like fabric,” Behnisch says. “It’s the signature of the building.” The curvaceous profile of the individual louvers recalls the spoiler on a Porsche 911—appropriate given that they were fashioned in Germany with metal forming techniques used by the automotive and aircraft industries. “They’re stationary,” Noblett says. “Clients hate movable sun shading systems because they are one more thing to fix, so these are optimized at angles to block summer sun while letting winter sun in.”

The building’s ventilation system is complex, yet deceptively simple. All windows, with the exception of those in labs, are operable. Noblett describes a system wherein all outside air is run through major atria, which allows the same quantity of outside air to be conditioned and reused within the building before being exhausted.

The building is programmed so the lower-level spaces are “public” while the upper reaches are reserved for laboratories. The atria are stunning, an indication of Behnisch’s agility with this building element, evident also at the Behnisch-designed Genzyme Center in nearby Cambridge. The spaces have a spare, industrial feel with exposed infrastructure and sealed concrete floors. The backdrop is white and light gray, which contrasts with colorful modern furniture peppered throughout. Ivy hanging from a horizontal planter is a puckish reference to the older Harvard campus across the Charles River. It is axiomatic in academic research buildings that the interiors be designed to promote social sustainability, which includes casual interaction among students, professors, and researchers at all levels. Noblett points out that “there are miniatria throughout the building” with break areas and small kitchens to facilitate spontaneous encounters.

“Engineers are a bit nerdy. They sit at their screens and space out. They could be on the moon and no one would care,” Behnisch says. “We talked a lot with Harvard about how we could bring them together.”

Behnisch concludes: “To make a great building, you need good clients and fantastic engineers as users. Here we had them both.”

You may also enjoy “Behnisch Architekten Completes an Energy Test and Simulation Lab in Germany”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.