March 18, 2020

American Archetypes Are a Calling Card at the Catskills’ Urban Cowboy Lodge

The latest venture from Lyon Porter and Jersey Banks embraces rustic twigwork, bandana motifs, and Pendleton fabric.

As I speak with Lyon Porter, he pokes at a fire inside his newly renovated 19th-century lodge in Big Indian, New York. Like many of the other elements that define this place, the Urban Cowboy Lodge, the fireplace was handcrafted by a local artisan—a mason, using stones sourced from a creek that runs through the property. All around are mainstays of pioneer Americana. You could say it’s a kind of museum for the genre: There are wall-mounted trout, plaid flannel curtains, deer-antler chandeliers. It looks like somewhere Paul Bunyan might steal away for a weekend.

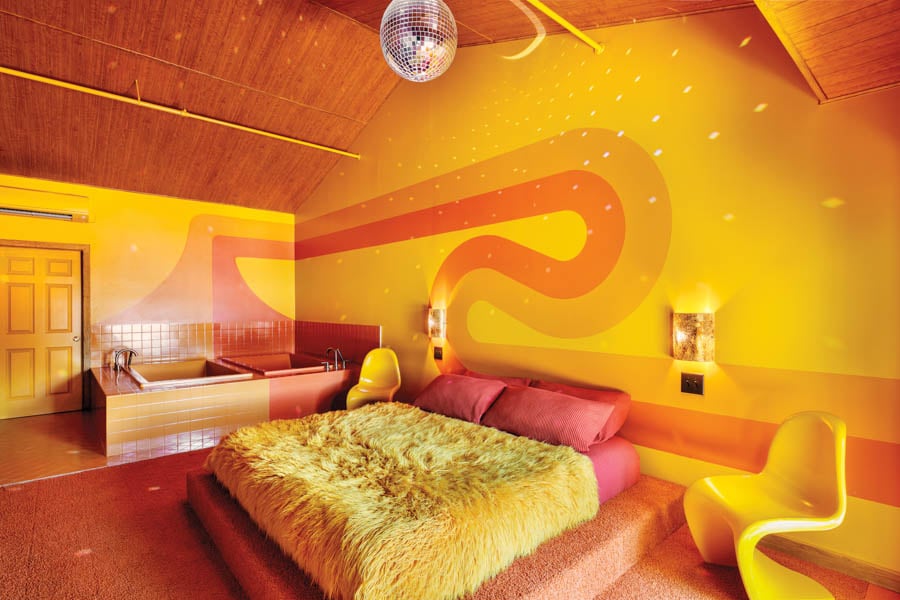

The 28-room upstate retreat isn’t Porter’s first rodeo. Together with his business and life partner, Jersey Banks, the designer-developer creates hotels that tap into romantic whimsy. The Urban Cowboy Catskills is their fourth venture: They’ve also built an Urban Cowboy in Brooklyn, and another in Nashville. And in a former motor lodge in Music City last year, they opened The Dive Motel & Swim Club, a supergraphic-studded and shag-carpeted party palace. Less Wild West, more Wild Cherry.

As different as those two aesthetics might be, there are through lines that make the projects definitively Porter and Banks’s: commitment to regional craft traditions, the use of handpicked antiques, and a maximalist’s eye for surface and pattern. But, says Porter, “the smell when people walk through the door is just as important.”

The Catskills lodge’s muse—the cowboy—is a telling symbol of core American values, a classic Western hero, and the archetypal self-made man. The fact that all these attributes have been problematized from every possible angle does not bother Porter or Banks. Rather, it’s the “play between softness and masculinity” that interests Banks, who has incorporated such dualities into the design. See in the rooms, for example, the tin-and-glass hanging lamps the couple found while antique picking: “[Each fixture has] this industrial feel with the tin, but the glass classes it right up, making it feel soft and fragile,” Banks explains. In a lodge characterized by tree-branch tables, camping lanterns, and century-old sports equipment, the lamps, by contrast, feel “really pretty.”

“[Porter] uses classic American motifs but turns [them] into a handcrafted wallpaper that fully wraps the room,” says Phil Hospod, a hotel developer who also collaborated on the Catskills Urban Cowboy. And that wallpaper fully wraps the room, creeping up the walls and covering the ceiling in a dizzying pattern. Each block was hand-printed and pasted by one man, Clinton Van Gemert of Printsburgh Wallpapers, and every print is a little different, resulting in what Porter describes as a “wabi-sabi that makes crooked walls go straight.”

This rustic style supports what Porter sees as American “romantic nostalgia,” an idea that has its precedent in design history. In the age of industrialization, the aesthetic was a part of the broader Romantic movement in America—one that advocated a simpler way of living rooted in the natural world. Henry G. Law, William C. Tweed, and Laura E. Soulliere argued in their 1977 book National Park Service Rustic Architecture 1916–1942 that this political atmosphere “restructured the American concept of wilderness,” laid the foundations for the national park system, and helped establish a visual identity for the emerging program.

What a spray of branches, or gnarled antlers, or, yes, even trout in suspended animation reminds us is that nature follows its own formal rules. Furniture that incorporates these irregularities results from a dialogue between nature and an artisan ready to embrace imperfection. Feeling, not prescription, is what counts, and Porter’s method correspondingly embraces intuition and idiosyncrasy. “I don’t mood-board, I don’t Pinterest, I’m not formally trained, and the way I design drives everyone mad,” says Porter. He points to a red cedar Adirondack tree growing from the floor and wrapping the lobby’s custom black-willow bar. “There is no way I could’ve CAD-ed [that] out.” (Both the lobby trees and the bar came from masters of the twigwork tradition—Judd Weisberg and Rick Pratt, respectively.)

At Nashville’s Dive Motel, where Americana takes on a ’70s inflection, Porter and Banks made similar overtures to craft—this time of the disco cowboy variety. And like the Catskills lodge, the structure—a motor inn—is itself an icon of American design. Porter notes that every generation has its own associations with motels: “I’ve stayed in motels where they have blood on the sheets and people screaming next door, and it’s not a great experience.” But for his parents, the motor lodge might evoke family vacations and the freedom of the open road. While Porter admits that some of his guests might not have ever stayed in a motel, younger people recognize something rock ’n’ roll about them.

For the most part, his and Banks’s environments are aesthetically convincing, and convey the feeling of authenticity because of era-specific objects. “You can’t fake a real antique. You can’t fake something that has a soul to it,” says Porter. But the objects ultimately help curate idealized visions of escape through “clean,” romanticized versions of classic American typologies. In a way, they create a safe space purposely distanced from the working-class realities found in the motels and dive bars that can still be seen from the highways of small American towns (and not just the glitzy grid of Instagram). One only has to take a drive through the sea of vacancy signs in Cherokee or Maggie Valley, North Carolina, to see that the motor lodge is not a dead typology, but one struggling to hang on. The Dive Motel is not a substitute for the real thing but purely an imagined place of the past, designed to provoke fantasy and sentimental longing. But can people be nostalgic for something they haven’t personally lived through?

Those arguments aside, all of Porter and Banks’s properties go back to the design of engrossing environments—ones that absorb the inhabitant into narratives told through decoration, whether or not that experience is known firsthand. There is a comfort to it associated with entering someone’s home and learning about them through their family heirlooms and the books that line their shelves. At the end of the day, the duo wants to create pleasurable environments that “envelop you, bring you in, and transport you.” By embracing the mundanity of everyday objects, Urban Cowboy and The Dive Motel tell collective stories by embedding North America’s complex mythologies, histories, and traditions in every room.

You may also enjoy “Nashville’s High-Kitsch Hideaway Is Full of Retro Charm.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]