December 4, 2017

After #MeToo, the AA’s Celebration of Women in Architecture Is More Necessary Than Ever

The legendary London design school mounted AA XX 100, showcasing a century of women-led architecture.

On an unseasonably warm October day 100 years ago, four female students entered the hallowed halls of the Architectural Association (AA) in London, ready to make history. This moment, when the legendary design school admitted its first women pupils, is the point of departure for AA XX 100, currently on display at its in-house gallery. Stepping back from architecture’s present pseudo-equality purgatory, this intriguing show reveals a long legacy of women who, for a century and counting, have faced down the forces of institutionalized and professionalized sexism.

The exhibition, part of a larger series of programming honoring the centennial, is rich with archival materials including photographs, models, publications, and other ephemera, which weave around the Georgian townhouse’s central staircase like beloved family portraits, flanking the student café bar on the first floor and even bumping elbows with the Digital Prototyping Lab in the basement. An early highlight is a fierce text written by Winifred Ryle, one of the AA’s “first four,” that was published in March 1918. Ryle’s essay is a riposte to her male peers, who griped about the integration of women on the building site. (But how will she climb scaffolding, they fretted, how could they order workmen around?) Having dispensed with these objections, however, Ryle concludes on a stoic note. As to the “experiment of the female architect,” she wavers: “Time alone can show us the result.”

Despite her reservations, it’s likely Ryle imagined something more progressive than today’s “woman architect,” a PR buzzword that reeks of second-tier status—and which AA XX 100’s co-curators, the architectural historians Elizabeth Darling and Lynne Walker, take pains to distance themselves from. “We wanted to underscore how the stories of women at the AA parallel the stories of women worldwide throughout the last century,” Darling says.

This parallel method traces the feminist movement and other key socio-political events of the 20th century, beginning with the First World War. Lagging far behind its peer schools (the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the Helsinki Polytechnic Institute, and MIT all boasted female graduates by the late 19th century) the AA only began with accepting female students in 1917, and only then to curb plummeting wartime enrollment rates. (The measure also helped foot the tab for the AA’s new digs in Bedford Square, which it moved into that same year.) It is this contextual criticism that makes the exhibition feel less of a nostalgic memorandum than a sober evaluation that’s keen to paint a bigger picture.

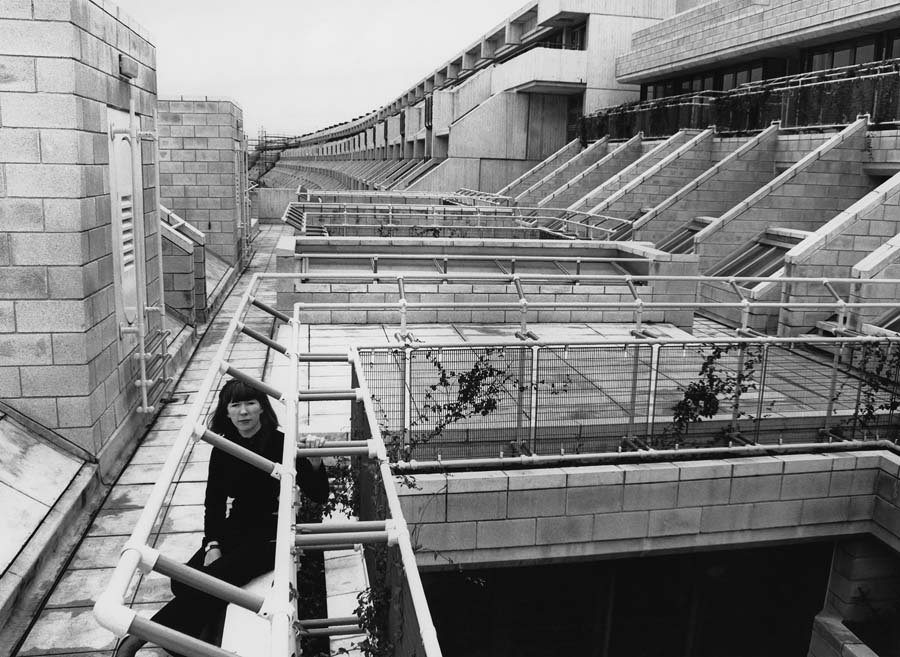

We tend to talk about women in architecture through a reified cast of characters, a tack Darling calls into question. As she puts it, “before the Zaha Hadids of the world, there were women like Judith Ledeboer and Mary Crowley in the 1910s and ’20s fighting the same gender hierarchies.” Somewhat at odds with this goal is the amount of floor space given to such recognizable names as Amanda Levete, and, indeed, Hadid, whose Hong Kong Peak (1983) and Trafalgar Square (1985) projects are immediately encountered upon entering the exhibition.

Still, no one can argue that AA XX 100 failed to give credence to those who have historically flown under the radar. The curators have been careful to highlight skillful designers, many of whom—Dorothy Hughes in Kenya, Jane Drew in 1930s Ghana, and Gillian Hopwood in midcentury Nigeria—worked on a global scale. The work of 1980s feminist design co-operative Matrix is given deserved treatment, as is the contemporary all-female practice MUF, which works at the intersection of art and landscape architecture.

Across the board, there is a unifying theme of opportunism and experimentation that in itself inspires. AA women were (are) constantly breaking new ground; whether in school or across oceans, their work was (is) almost always collaborative, and highly responsive to both user needs and local context. At the back of the house, we get a mesmerizing spread of student thesis projects including Janet Kaye’s Open Borstal for Girls (1957), Eldred Evans’ Concert Hall (1960), and Amanda Marshall’s Pier in Cornwall (1977-78). Moving overseas, AA XX 100 gave a delightful anecdote of Drew’s anthropological-grade “fieldwork” for a housing project in Chandigarh, India, where she approached the street sweepers who would later live in the building to discover what they sought in a house.

From this presentation emerges, somewhat inevitably, the model of the husband-and-wife partnership. Here, Eldred Evans (of Evans + Shalev), Su Rogers (of John Miller + Partners), and Denise Scott-Brown (of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates) are featured to varying degrees alongside their male counterparts in knockout projects such as Cambridge Jesus College Library (Evans + Shalev, 1996) and the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery by Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, 1991). Darling and Walker pick at the compulsion to “split evenly” the credit between the male and female partner, which hints at a larger flaw in the system—where are the non-hetero, non-marital, non-neurotypical collaborative practices?

The importance of internationalism emerges as another central theme. “There has always been a diaspora instrument to the AA,” explains Darling; indeed, 90 percent of AA’s current students hail from overseas, and this melding of cultures is an integral part of the school’s identity. The exhibition delves into the stories of Angeline Yuen Mo-Ting and Esther Yuen Mo-Yow, the AA’s first Asian students admitted in the ’30s, not to mention the influx of female Australian students that peaked in the ’70s and ’80s. Moving beyond Bedford Square, the global perspective is evident in the volume of featured work built by AA alumni abroad in continental Europe, as well as former British Colonies in Africa and India over the course of the 20th century.

Yet in spotlighting the gender hierarchies historically at play within the discipline and skimming the racial politics of the AA’s past, it feels remiss for AA XX 100 to ignore the power structures of colonization and Western capitalist exploitation that enabled young graduates to cut their teeth on building projects in Africa during the ’50s and ’60s. This parallel abuse of power levied by male students upon their female counterparts and AA alumni upon the African continent is unrecognized by the exhibition, even in its inclusion of work by husband and wife duo Hopwood + Goodwin, who moved to Nigeria in 1955 to found their own practice. There, they solicited work from companies such as Shell, Reckitt Benckiser, and Nestle, for whom they built factories and other colonizing infrastructures.

The topic of internationalism is increasingly salient today. How will the school’s legacy of cultural diversity be impacted by Brexit? It’s a troubling episode of deja-vu from Winifred Ryle’s wait-and-see mantra of 100 years prior. Likewise, it feels a charged moment to host an exhibition tackling the history of internalized sexism within the discipline. This is the era of Harvey Weinstein and Knight Landesman, of #metoo and #notsurprised. It’s a horrifying and ecstatic time of social and political undoing, where the weighted power relations of fear, shame, and vulnerability that sustained the denial, ignorance, and silence surrounding gender-based abuses of power are coming loose. This is the era we collectively confront the ugliness of a sexism so deeply interred in every sector, from Hollywood to high art. Is architecture next?

As Anna Winston argues in Dezeen, probably, yes. While the architecture and design journalists take aim at their freshly enabled targets, the academic response is, perhaps unsurprisingly, more hesitant. “Education is always a fluid context where the hierarchies aren’t so embedded in what’s taught,” Darling suggests. Yet past the healthy debate of the classroom, the reality is that these standards still cut deep into the structural anatomy of the academic institution, as a place where female architectural historians “mysteriously disappear” at senior level, Darling later confesses. Moving beyond the ivory tower, it seems less about the repetition of progressive ideals within a screwed-up system and more about shattering that system entirely. One thing is clear: Unlike Ryle, we are not waiting another 100 years to find out.

You may also enjoy “Three Women Designers Blasting Through NASA’s Glass Ceiling.”