January 16, 2020

You Can’t Spell SOM Without Gordon Bunshaft

Relatively little was known about the driving force behind many of SOM’s most accomplished buildings. A new book fills in the gaps of Bunshaft’s biography.

You couldn’t invent a firm of more interest or appeal to organization theorists and historians of capitalism than SOM. Abjuring the atelier model, SOM reconstructed architectural practice in the multinational corporate mode, churning out slick, high-Modernist products as if by assembly line. In their turn toward “initialism,” founding partners Louis Skidmore, Nathaniel Owings, and John O. Merrill forsook the perks that come with name recognition; indeed, they seemed intent on obliterating their individual identities. The titles of the sanctioned monographs—SOM 1950–62, SOM 1963–1973, SOM 1973–1983, and so on—read like telegraph codes. So it’s no surprise that subsequent company heads and design leads eventually bridled against this self-abnegation, or that the public grew curious, but truly accurate apportionings of credit have often been difficult to come by, in large part because institutional methods did not value the question much at all.

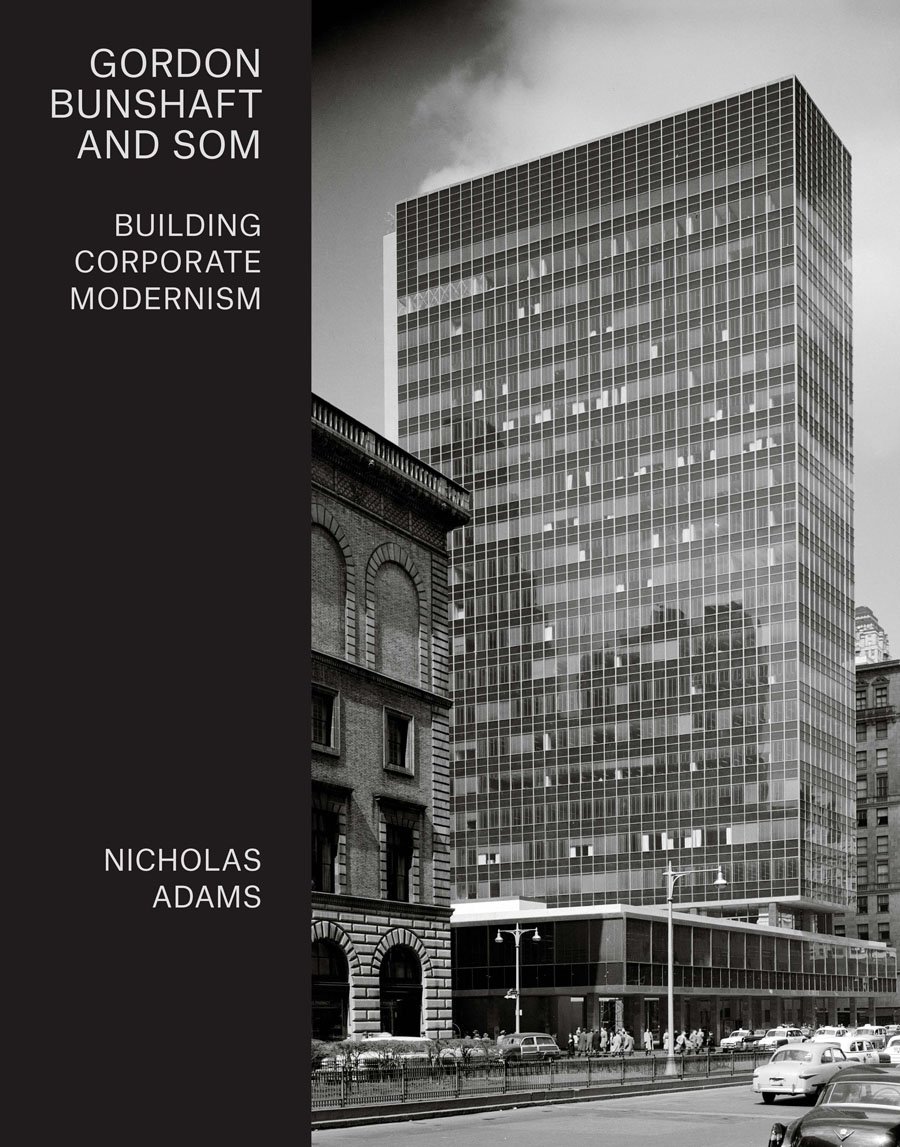

Excavating creative agency from these obfuscations can be difficult for the historian, but not Nicholas Adams. Adams’s latest work, Gordon Bunshaft and SOM: Building Corporate Modernism (Yale University Press), is an invaluable follow-up to his earlier Skidmore, Owings & Merrill: SOM Since 1936, but whereas the latter read the firm’s past through its key buildings, the former dwells on one of its most singular creative forces.

On the face of it, the job of elevating Bunshaft’s profile over and above his faceless associates seems retrograde: The myth of the solitary genius is exactly that. Adams has previously written that SOM was structured along the lines of “a federated group of city states or affiliated research teams.” Against this relief, Bunshaft emerges as a primus inter pares, and not a monarch. The architect wasn’t entirely wrong to tell a Newsweek reporter in 1959 that there “always has to be one dominant force, someone who comes up with the original design.”

Yet, the question of who exactly did what—who contributed this or that idea or solution—is an essential one, and the fact that clear dividing lines can’t always be drawn doesn’t justify anything less than the most dutiful inquiry. Just how dutiful Adam was in carrying out his research is demonstrated by an early passage, in which he agonizes over

Who set the bay width (and when)? Or the story height? Who determined the structural system and the material choices? Who proposed a new lighting system, or thought the old panel track system for the window covering unsatisfactory? Who found out that there was a new alloy available, and the new alloy made other design alternatives possible? Some senior designers put more flesh on the bones and some put less, offering a smaller or a greater role to the production department […]

It’s a research task complicated by substantial difficulties, such as the loss of much of SOM’s New York archives (due, in Adams’s assessment, to the attrition of office moves and storage costs in Manhattan) and the paucity of recorded matter from principal architects. Bunshaft’s laconic demeanor certainly compacted matters; as Adams admits in his introduction to the new volume, “Telling Bunshaft’s story would have been much easier had he been more communicative.” The architect didn’t pen a single article, didn’t deliver any lectures, made almost no drawings. His correspondence contained next to no design revelations. His Pritzker (’88) acceptance speech was the shortest to date. A lesser author might have tossed in the towel.

By contrast, Bunshaft’s life outside of SOM is very easily summed up, precisely because there was so little of it. Born in Buffalo in 1909 to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, he received undergraduate and graduate (in architecture) degrees from MIT and then worked for Edward Durrell Stone for a few months before landing at SOM in 1937. There he remained until his death in 1990. The conjunction of SOM and Bunshaft, the inability to extract the latter from the former, underpins Adams’s creative biography.

Adams structures his investigation around the 38 projects that Bunshaft asserted as his own for Carol Herselle Krinsky’s 1985 Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merill. His cardinal effort is to situate these within the broader organization of SOM, in which design work and administrative practice were thoroughly entangled. According to Adams, the responsibility for a project was shared by five employees: administrative partner, design partner, senior designer, project manager, and job captain. Bunshaft was administrative partner and design partner on 16 of the 38 projects, and generally acted as design partner on the remainder. The identity of his collaborators can be determined by and large, and Adams provides a thorough account of many who lent a helping hand, although a few are inevitably lost to history. It’s clear that Bunshaft gravitated toward a few select senior designers: He partnered with Roger Radford eight times, while he appointed Natalie de Blois, Sherwood A. Smith, and Whitson Overcash to the role on seven projects each. Adams traces the influence of each through the “family resemblances” evident in the (mostly) built works.

Bunshaft was generally parsimonious in doling out credit to these collaborators, however, though he was more prone to lend praise to lower-level production personnel than his direct peers. There were exceptions, namely in the praise he reserved for Natalie de Blois. (Bunshaft did not figure among de Blois’s late-career criticisms of SOM principals, whom she felt willingly ignored her contributions). Paul Weidlinger, whose engineering expertise enabled Bunshaft’s later shift toward sculptural concrete, received a bit more acknowledgement than most.

Bunshaft might not have had much to say about his own projects but thankfully Adams does, and he provides excellent readings of individual projects in chapters that parse out the stylistic phases of the former’s work. Of the Lever House (1952), still one of Bunshaft’s greatest achievements, Adams detects influences that can only be described as catholic, ranging from Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion (1929) and Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer’s Ministry of Education (1942) to the works of the delineator Raymond Hood. Adams places emphasis on the latter, whose mannerisms and lugubrious affect would have surely seemed passé by the 1950s. “The buoyancy of Lever House,” Adams writes, “depends on this irregularity, a jilted recollection of the late deco and early modern works of Raymond Hood.” Contrast this with Bunshaft’s odd, blunt sentiments:

Somebody likes to say Lever House is Corbu. Another guy says it’s Mies because it has thin mullions. And they’re both full of baloney. It’s modern and it’s probably influenced by Corbu’s pilotis and things, period. But it’s an insult to Corbusier. He would do a much more interesting building than Lever.

For all of his marvelous geometries, Bunshaft had little patience for the structural principles and logic that Mies had elevated to a gestalt. One Chase Manhattan Plaza (1962) is a prime example. Structural piers stand outside the building on its lengthier sides, falling “like pleats” while sitting flush with the structure on its north and south facades. It’s a solution that imparts “vertical dynamism and three dimensionality,” but it also suggests a workmanlike attitude to materials and their arrangement. “In effect,” writes Adams, “Bunshaft wants to say that an H-mullion is no more or less than what it is; it has no meaningful symbolic role.”

Bunshaft’s “rectangular” buildings frequently conceal internal irregularities as well. (Something similar could be said about Mies’s Seagram Building.) The elevator core in One Chase Manhattan is off-center so as to provide the south-facing offices with better light. The plan of the Pepsi-Cola Corporation World Headquarters (1960) in Manhattan cast the “core” off-center entirely; to accentuate the appearance of levitating floors, Bunshaft relocated the elevators and services to the rear of the structure, along a party wall.

Innovations of this kind can be found in other aspects of Bunshaft’s work beyond. What appeared as simple geometries often incorporated expressionist elements. Adams compares the mullions of the Union Carbide Building (1960) to “sparkling icicles,” and indeed, they played as much of a structural role as icicles do, exactly none. (Union Carbide is currently being demolished. RIP to a real one.)

Thick concrete exoskeletons began to appear around the same time. At the First National City Building (1960) in Houston, the curtain wall is set back a full six feet from its concrete frame. The rectangle and right angle gave way to increasingly sculptural shapes, none more so than the diagonal cruciform trusses of the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale University (1963), which Adams likens to origami. Even stranger and more wonderful things happened within these frames, where marble, prized for most of human history for its milky opaqueness and solidity, is tasked with translucence. That’s only the building envelope, however. Adams picks out the interior glass-encased pavilion containing the library stacks as being equally inspired. “[I]n these sepulchral spaces it is something of a surprise to find that the book tower is a playful replica of a Miesian bronze curtain wall with Seagram-like corner solutions,” he writes. “There is, in fact, no Bunshaft curtain wall that is more completely Mieisan than this tower.”

There’s much more to Adams’s study than the buildings, of course. The historian’s close look at Bunshaft and his wife’s considerable art collection and steadfast advocacy of the inclusion of art in his projects is worthwhile. Adams also details Bunshaft’s work on the Commission of Fine Arts in Washington, D.C.. When a commission member asked about the Hirshhorn Museum’s (1974) single loggia lending it an appearance of a piggy bank, Bunshaft’s reply was characteristically terse (and head-scratching): “You know what, you can call it anything you want. You can call the whole building an old penny or old coin. It looks pretty good in the renderings we have.”

Bunshaft remained inventive well into his ninth decade, a fact attested to by the handful of projects he completed in the Middle East, namely the National Commercial Bank in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (1983). With the advent of Postmodernism, however, his body of work fell out of fashion. The Postmodernists didn’t care for him, and the feeling was mutual. Bunshaft characterized the building of the period as “a joke” and dismissed Robert Venturi as “a hot rod who wrote a book.” Yet Bunshaft’s taciturn nature also made him an easy target. “His silence made him and SOM into a modernist rag doll,” Adams explains.

Monotony also set in at SOM, with Adams describing the production department turning at times into “a library of habitual results.” The art critic Hilton Kramer provided the most succinct barb up to that point: “Studying an SOM building is therefore a bit like reading The New Yorker: you marvel at all the talent, and then you marvel at how little difference it makes.”

But it’s easy to make too much of this critique, for as Adams very pithily argues, “Repetition has been integral to architecture throughout history; good solutions are reused.” This is the source of both good and lamentable things. Bunshaft-like elements can be found in many SOM buildings beyond the canonical 38. Not all of these matched Bunshaft’s best, but some—the 1963 Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs and the 1958 Inland Steel Building in Chicago—gained from their association to his legacy, one that, thanks to Adams, we might now understand better than we ever have.

You may also enjoy “A New Idea in Architecture? No New Buildings.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]