April 7, 2025

How Architecture Must Evolve to Embrace Timber-Based Design

If there’s one defining trend in American architecture over the last decade, it’s the rediscovery of wood as a construction material. Mass timber buildings—made from large wooden panels, columns, and beams—are rising across North America, with developers racing to construct the tallest wooden tower. A new contender, the 32-story Edison in Milwaukee, just broke ground and is set to claim the title of the tallest mass timber building in the Western Hemisphere.

But why are American developers, architects, and builders all timberstruck? There are the carbon emissions—wood pulls down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as trees grow, so these buildings are a tool in the fight against climate change. Plus, they are quick to construct and can be cheaper to build. So should we start building everything out of wood?

In the latest episode of Deep Green, produced in partnership with Mannington Commercial, METROPOLIS editor in chief Avinash Rajagopal speaks with experts to unpack the potential of mass timber. In Part 1 of the discussion, Columbia University professor and author of Designing the Forest and Other Mass Timber Futures, Lindsey Wikstrom joins the conversation to explore how architecture and construction must evolve to fully embrace timber-based design. Read an excerpt from her discussion with Rajagopal below or listen to the full episode on the Surround Podcast Network.

Avinash Rajagopal (AR): What inspired you to do your research, write your book, and why is this a good time to ask some critical questions about mass timber?

Lindsey Wikstrom (LW): I was teaching at GSAP and leading an Advanced Studio at that time, which asked me to create a syllabus introducing students to nature for the first time.

This was because the studios leading up to that semester were focused urban sites. So, for the first time, students were to come face–to–face with territories of production rather than territories of consumption. We know this best with the phrase “farm to table.” It’s the most common co–located production and consumption experience. That’s how this got off and rolling, and the site I chose was in New York State in the Hudson Valley watershed.

I found myself joining that community and learning about what’s at stake here. What are people working on? What are people thinking about? What are the hurdles? I was learning a lot, really listening, and becoming a student, while also teaching this studio and helping students learn about mass timber as well.

I met folks like Susan Jones, who has a great community multidisciplinary practice that is not only about building beautiful pieces of architecture but also about working with the Department of Buildings in order to level up their codes. Taking time off from her practice to do that work suddenly expanded the way we practice architecture.

This got me thinking: What’s a good primer? What do I assign my students on the reading list? There were books that covered bits and pieces—I have some—but none were as comprehensive in challenging greenwashing or asking the question: Who gets to be part of this future?

So, I was hoping that my book would build on the existing knowledge, which is just starting. We’re at the beginning of this material era. Since we have this next 100 years to rewrite how materials move from territories of production to territories of consumption—and, hopefully, back in a more cyclical way—we also have the opportunity to determine who gets to profit from that, who gets to participate, where those materials go, and which communities will be healthier because of it. To me, it just gave it much more urgency.

AR: Why do we care about carbon for mass timber? How does mass timber help with carbon?

LW: First, from a global a scale, half of annual carbon emissions are contributed by the built environment, and of that, 25 percent of global annual carbon emissions—or greenhouse gas emissions—comes from just turning on the building.

For us, when it comes to carbon, energy efficiency also makes you more money so you can save money. The less energy you use, the more it tracks with capital, so inevitably, the market is driving down operational energy. The flip side is embodied energy—the fossil fuels it takes to heat or cook the materials we use to build the built environment.

Specifically, concrete, steel, and aluminum require massive amounts of heat, which is called industrial heat. Industrial heat contributes more carbon emissions to the global greenhouse gases than all transportation combined.

If we were to just use mass timber instead of 20 percent of the concrete, it would already save the planet. I hate to say something so easy like that, but just a little bite of that market with biogenic material has a massive impact.

When we think about carbon from a forest perspective and why mass timber is so impactful, it is because for the first time in the history of cities, we can now replace concrete and steel.

Then you get into this deeper question of the quality of the forest. And that has everything to do with carbon as well because if you are relying on monocultural forests that are clear-cut harvests, those forests are not going to be resilient. We must figure out how to get on the cycle of the forest—where we’re harvesting multiple species in a way that’s not destructive to the root systems—so that we can feed the construction industry without depleting the forest.

AR: To me, that is the beauty of mass timber. It’s the one place where addressing carbon emissions allows us to also address some of the other things we’ve not been very good at in the built environment. Suddenly, we start to care about life on this planet, species on this planet, what will it take for us to have enough healthy forests.

LW: If we were to tomorrow say that all construction in New York City had to used wood from New York State forests, could we maintain the same rate of construction that we’ve been doing? Could webuild the same buildings and essentially replace them one-to-one? Just like architecture—no one’s designed the same building—nobody designs the same forest. You have so many parameters to take into account.

Trees grow so prolifically when you keep them in the biodiverse environments that they really enjoy. So, you can figure it out. The volume is not the question—it’s more about the choreography. How do we harvest? How do we bring this management scheme across private property boundary lines? How do you get everybody to agree to do this? It’s more of a social challenge than a volume challenge, and it is changing the landscape of mass timber as we speak.

AR: We’re not used to thinking about our materials quite in that fine-grained way. How does that change the way we function? As architects and designers, if we must now start thinking about materials—mass timber, in this case—that have a life but are also biodiverse. How would that change architecture if we started to have to think about all that?

LW: One example: Before OSB sheets were used in the built environment—before that product was designed or invented—aspen trees were a blight on forest owners. They couldn’t get rid of them fast enough. The trees grew so fast and had no value, which devalued the forest because they had to spend so much to get rid of these trees that were so prolific. And then somebody invented OSB, and now aspen trees are the most cultivated tree on the planet.

To take it further, OSB has a distinct aesthetic, a specific color. Now, the more you use it or see it, it has a culture. It has this kind of industrial, off-the-grid feel. We have associations with that material.

When I talk about choreographing material, I mean that as a designer, you have an impact across all of these scales—especially aesthetics, which now have the potential to unlock incentives for cultivating certain species.

Demand has something to do with it. I like to think about how species-based design cuts across all these scales—from the forest to the experience of being in an interior environment, sitting at a wood desk, or living inside a mass timber space.

I’ve spoken with folks who live in mass timber apartments, and the smell is different. The sounds are different. In a mass timber building, you hear the wood moving and it’s not an echoey sound. It’s a different kind of sound. It’s very subtle and it also depends on how you design your buildings to be acoustically treated.

This is just the beginning. We’re just starting to get really good at using mass timber in the urban environment. If you consider concrete and steel, they’ve been modernized for the last 120 years. We’ve been getting good at designing with concrete and steel for 120 years. We’re about 10 years into mass timber.

So just imagine what is coming. It’s just an amazing amount of expertise that’s on the way. It’s exciting to be in these early days. I feel like we’re going to look back and think, wow, that was amazing. We did that!

AR: We’ve gotten so used to thinking about the built environment almost in contrast to the natural environment. We talk about those two things as two separate categories.

LW: I agree. I’m so glad you picked up on that.

We’re taking care of our building much more like we take care of our bodies. I love this comparison too. My clients—especially those used to concrete and steel buildings or plaster walls that don’t require the same level of maintenance—often wonder: How do you maintain wood in a way that prevents rot, termites, or catastrophic failure?

I like to compare it to taking care of your body. You do things because it’s part of maintaining a level of health and your own vision for your aesthetic. And so that’s how we might start to think about our spaces that we inhabit, that care is part of their lifespan.

Listen to “Why Architects Are All In On Wood” on the Surround Podcast Network. This season of Deep Green is produced in partnership with Mannington Commercial.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

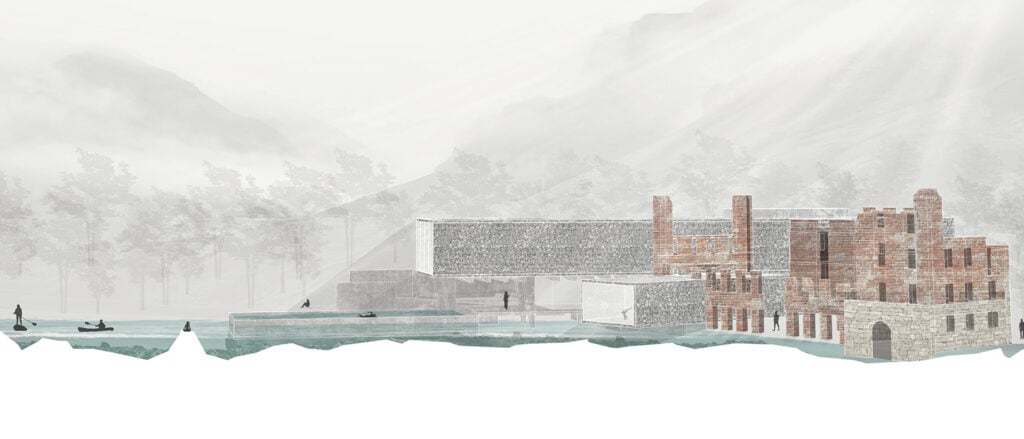

These Architecture Students Explore the Healing Power of Water

Design projects centered on water promote wellness, celebrate infrastructure, and reconnect communities with their environment.

Projects

KPF Reimagines the Arch in a Quietly Bold New York Facade

The repetition of deceptively simple window bays on a Greenwich Village building conceals the deep attention to innovation, craft, and context.