December 21, 2021

Can Architecture and Design Facilitate Healing?

What has made [the hospital] so indifferent to the human experience? Why the indignity? Where is the design?

Michael Murphy

The book is hardly sparing in its diagnosis on hospital architecture, “its complications are prevalent, its authorship multiheaded, its forms jumbled, incoherent, inelegant, and bipolar.” The results are often bad, facilities designed to provide care to persons who are unwell are confusing, frightening, or worse. Murphy wonders “What has made this place so indifferent to the human experience? Why the indignity? Where is the design?”

An early overview in The Architecture of Health is telling, consisting overwhelmingly of plans with an occasional axonometric; it becomes clear that the appearance of these buildings is beside the point in the longue durée. This design approach still demands attention, following the practical demands that explain just how hospitals have evolved. We’re a long way from the basilica hospitals that begin this list, but early proximity to the altar mirrored a more fundamental organizational relation, that of patients to nurses, a requirement whose logic is purely internal and has often been achieved with few windows or any coherent relationship to a building’s exterior.

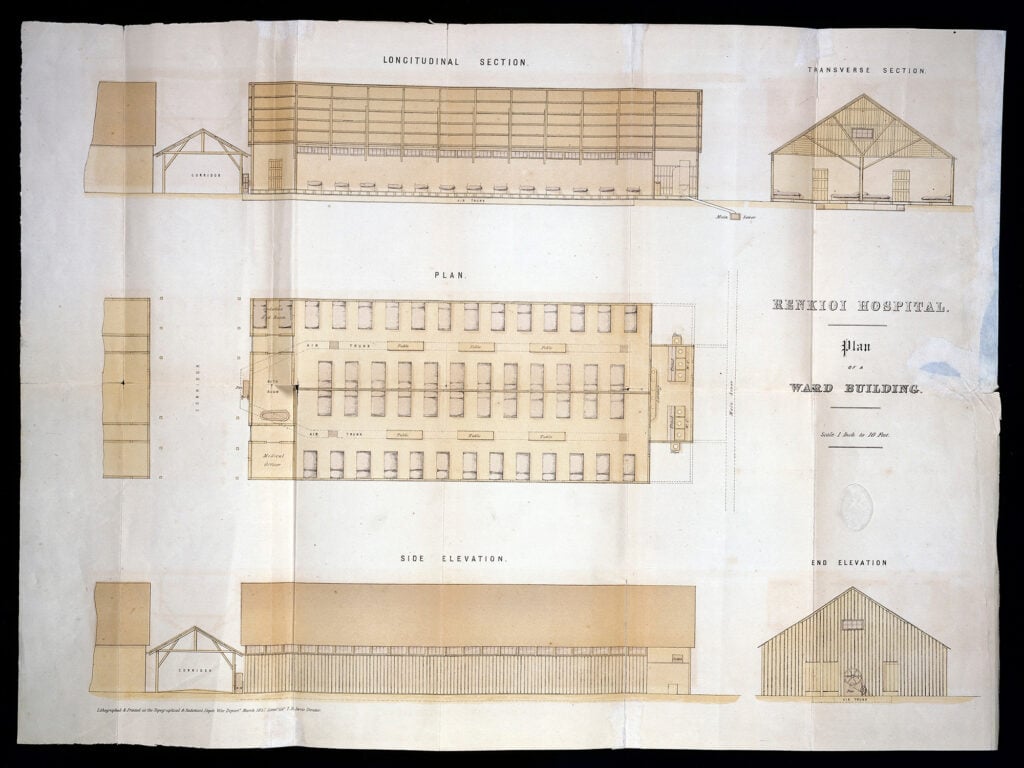

Rising awareness of the importance of ventilation, with great credit to hospital reform pioneer Florence Nightingale, rendered the building’s envelope more important. Isambard Brunel’s prefabricated field hospitals were an early vindication of this insight in the Crimean War; mortality rates at his Renikoi Hospital were about three percent; those at a barracks hospital nearby had been over forty percent.

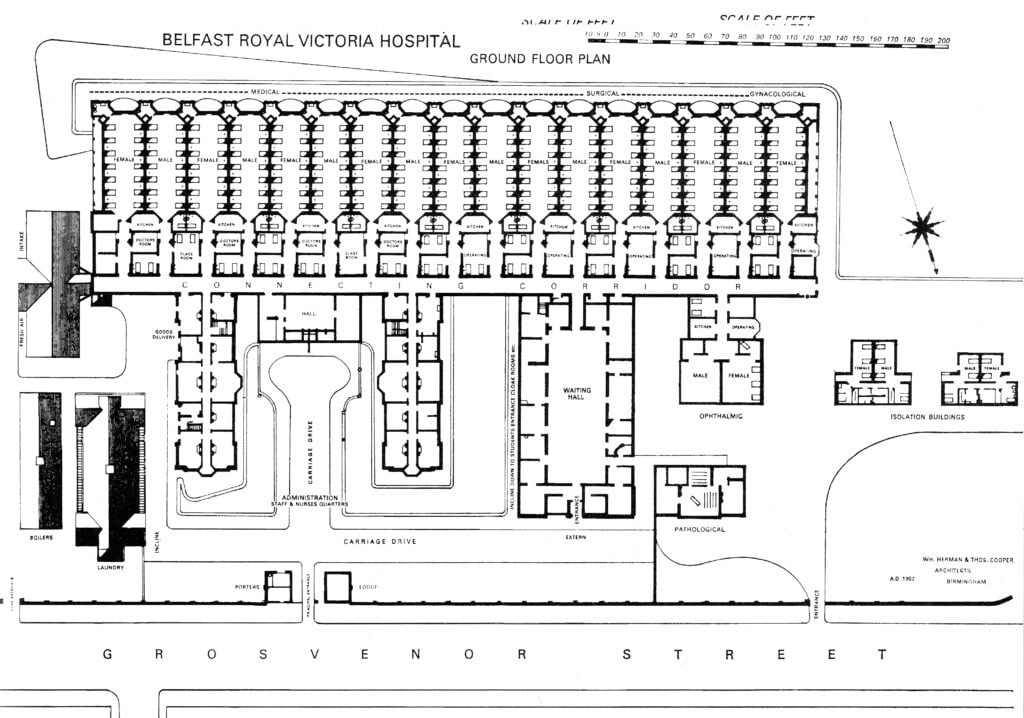

The age of operable windows wouldn’t last, however, as machines took over. Reyner Banham naturally crops up, with the authors noting his early attention to the consequentiality of the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast, as the authors observe, “the first to implement forced-air ventilation as a means of controlling the indoor air environment and regulating its heat and humidity.”

The rise of the hermetically sealed box meant that hospitals could again turn inward, swelling and rising in ways that natural ventilation would not have permitted. Albert Kahn’s commission for the University Hospital in Ann Arbor (complete with two miles of hallways) leaps off the page as emblematic of this scaling-up, “it was a closed system in which patients moved along an assembly line from one service to another—a factory for healing.”

The few healthcare facilities that are in the design canon appear more often as outliers than as replicable pinnacles. Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanitorium in Finland is wonderful but intrinsically small and inflexible. Others addressed the requirements of the moment but grew outmoded due to trends entirely beyond their control. Bertrand Goldberg’s sadly departed Prentice Women’s Hospital was well-conceived, “the top exemplifies the elemental ratio of nurse to patient; below is the control center of systems, operations, and technology.” The trouble is that mechanical elements were not content with this space and continued to demand evermore.

Efforts to articulate mechanical requirements certainly intrigue: E.Todd Wheeler’s very visible ventilation on his St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital in Chicago or Louis Kahn’s Richards Laboratories in Chicago. His Salk Institute was a rare building effectively future-proofed, with half-floors for mechanical elements more than any needs upon construction.

Even when future modification was seen as inevitable, it was difficult to tell just what form this would take. Eberhard Zeidler’s McMaster Health Center in Hamilton, Ontario was built as a series of replicable modules, a frame that worked, but most didn’t. Labyrinths often result. Who hasn’t made three lefts and two rights to realize you’re still two floors below the skybridge? The account features occasional heroes but plenty of villains, with Bellevue as a not-remotely-atypical avatar of “institutionalization and dehumanization.”

And the world delivers ever-new challenges. The sealed environment that became de rigeur was suddenly proven faulty by the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors point to Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City moving patients out of more recent wards into a building from the 1930s—because it still had operable windows.

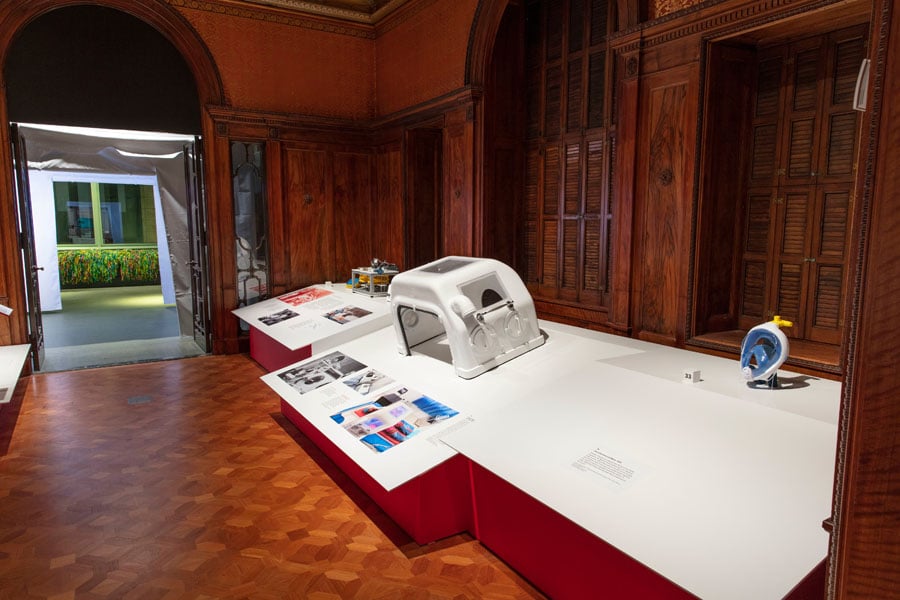

MASS Design Group’s especially thoughtful design of the Butaro District Hospital in Rwanda, designed to provide ventilation, views of nature, and effective care, is a very welcome coda to the volume, and featured prominently in Design and Healing. With a broader focus on open-source design, the exhibition showcases both innovative recent buildings and other medical technologies, from a range of masks to a low-cost cot for a Cholera treatment center in Port-au-Prince to smart thermometers to both UK and Bangladeshi negative pressure ventilators devised at a fraction of the cost of prior ventilators. Design, like illness, is a problem that can never be entirely overcome, but progress is always possible.

Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics is now on view in Cooper Hewitt’s Design Process Galleries through February 20, 2023.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Viewpoints

Archtober Invites You to Trace the Future of Architecture

Archtober 2024: Tracing the Future, taking place October 1–30 in New York City, aims to create a roadmap for how our living spaces will evolve.

Projects

Kengo Kuma Designs a Sculptural Addition to Lisbon’s Centro de Arte Moderna

The swooping tile- and timber-clad portico draws visitors into the newly renovated art museum.

Products

These Biobased Products Point to a Regenerative Future

Discover seven products that represent a new wave of bio-derived offerings for interior design and architecture.