October 7, 2022

Can We Design for Happiness?

Above: Happy Street, a 2019 installation in London by designer Yinka Ilori, was created to transform a forbidding bridge underpass into a space that puts a smile on pedestrians’ faces. © LUKE O’DONOVAN

There is no universal recipe for pleasure and delight, but some ingredients are foundational such as safety, comfort, inclusion, and the freedom to make our own choices. Many of these feelings have evolutionary bases. Visit pretty much any Frank Lloyd Wright building and you will be welcomed by low-ceilinged entrances that open into magnificent tall spaces. This was meant to reinforce the feeling of shelter that humans once felt when living in caves. In public buildings, the need for shelter could mean adopting human-scale proportions that make us feel enveloped instead of exposed. And in cities, it could be fulfilled by something as simple as a row of trees, or even umbrellas at an outdoor café.

“Part of it is that we naturally evolved to be under tree canopies and feel safe in that way,” says Erin Peavey, an architect and design researcher at architecture firm HKS who also has academic training in psychology. We evolved in small tribes, says Peavey, and countless studies confirm that we live happier, longer, and healthier lives when we’re connected to other people. “There’s nothing that makes us feel better than feeling wanted,” she says, as long as we at least have the choice to engage in a social activity. At the University of California San Diego, for example, HKS designed various degrees of connection, where a single dorm room is part of a small cluster of rooms, which is connected to a hall that is linked to a larger building with bigger connecting spaces—“like a Russian doll of architectural connection,” says Peavey.

As loneliness continues to rise in the United States—a post-pandemic study commissioned by Cigna found that more than half of all American adults can be considered lonely—understanding the benefit of connection is crucial. One landmark study from 1998 showed that a lack of social connection is more detrimental to our health than smoking or high blood pressure.

HAPPY BRAIN, HEALTHY BEING

The relationship between health and social connection—and ultimately happiness—has deep roots. For the ancient Greeks, happiness could manifest only in a community, but they didn’t really have the concept of happiness that we do today. Instead, they used the word eudaimonia to describe “the good life.” This encompassed both spiritual and physical well-being, and according to Peavey, it was reflected in the kinds of buildings that were built at the time. “[Eudaimonia] was an embedded part of the Greek temples that were some of the first ways that we think of architecture of health and healing, because that’s what they were really about,” she says, noting key features like sunlight, nature, and water in the form of healing baths.

HKS is now putting the pursuit of eudaimonia to the test in the workplace. Earlier this year, the firm partnered with The University of Texas at Dallas’s Center for BrainHealth for a six-month training program on brain health. The program includes online training, think tanks, and daily brain exercises designed to optimize almost 200 employees’ nervous systems. It seeks to improve their emotional balance, compassion, and resilience—all of which can help architects achieve a balanced lifestyle, but also be more attuned to the needs and challenges of their clients, with the ultimate goal of becoming better innovators.

That brings up the important distinction between individual contentment and organizational happiness. The Industrial Revolution in the 18th century marked a shift in the way people thought about happiness. In one sense, happiness seemed more attainable, as people lived healthier lives thanks to germ theory and the decline of epidemics (so much for that), but also more comfortable ones, with technological advances like modern heating and electricity.

But capitalism simultaneously put an emphasis on productivity and efficiency. Take the office cubicle. “The cubicle was probably [about] looking into the happiness of an organization, which could equal financial performance. But did that really equal happiness for everyone?” asks Susan Chung, a senior research program manager at HKS and a key driver in the firm’s BrainHealth training. “Now with the pandemic, we’re getting back into understanding what’s the meaning and purpose behind our individual happiness within an organization.”

HAPPINESS AT WORK

The pandemic, and the Great Resignation that it fueled, has inspired a wave of creative hand-wringing over ways to attract people back to the office and make them feel supported and seen. But here’s the problem: How do you build a strategy to make people happy, and then how do you measure its success? Putting a number on something as abstract and personal as happiness can be a challenge, but one company is proposing a solution.

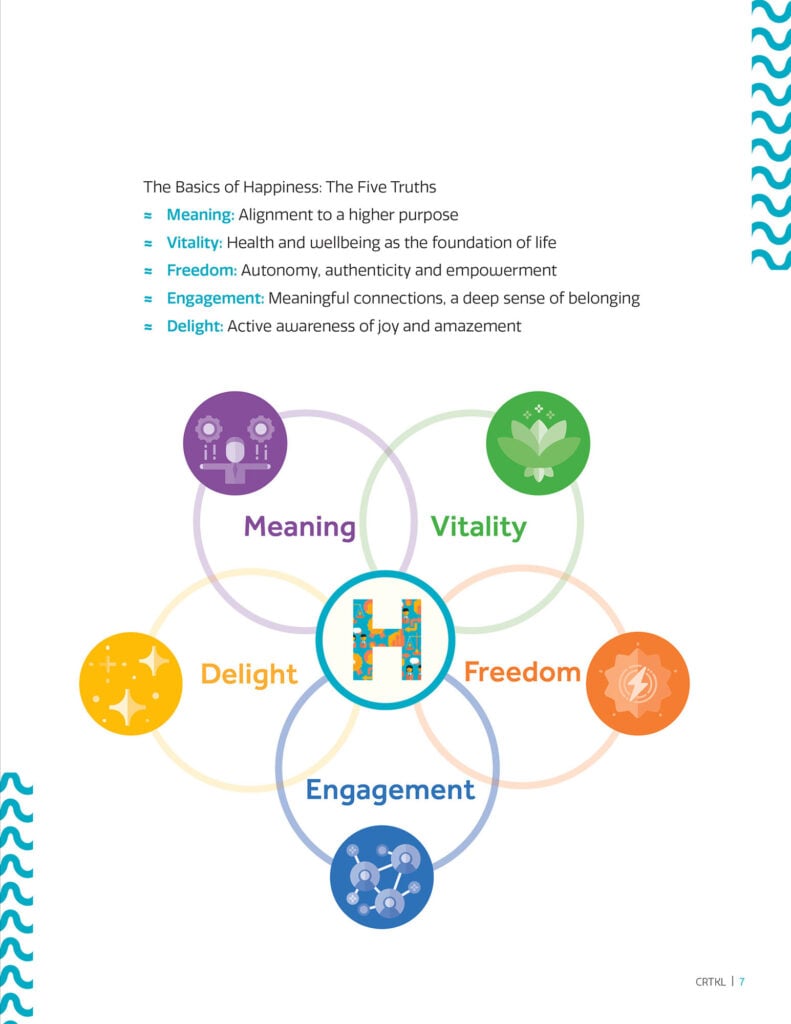

Earlier this year, CallisonRTKL launched the Happiness Ecosystem Index (HEI). Created in partnership with Delivering Happiness, which describes itself as a “coach|sultancy,” and Egyptian developer Mountain View, HEI acts as a guide for organizations, communities, and ultimately designers who want to improve the connection between buildings and people. “The intent was to take what was done for sustainability with LEED, and for wellness with WELL, and think about that more holistically,” explains Jodi Williams, a principal at CallisonRTKL.

Unlike LEED or WELL, however, HEI is less of a point-based system with a rating, and more of a roadmap. It’s broken down into five categories called “Truths” (meaning vitality, freedom, engagement, and delight) and includes 200 design actions. Organizations fill out an initial survey (a bit like the Myers-Briggs personality test) to get a sense of their strengths and weaknesses. If a company’s interested in making a change, it can then take a deeper dive in the form of a consult with CallisonRTKL and use the final assessment as the basis of a design brief. To date, HEI has informed the design of an office building in Egypt and several of CallisonRTKL’s own offices, including a retrofit in Washington, D.C., and a new lease in London.

Ultimately, though, happiness is a complex condition and doesn’t come tied up in a neat little bow. “There’s beauty in sadness, and we don’t need to strive to be 100 percent perfect; that’s not a realistic goal,” says Williams. “Happiness is about the ability to be who you need to be, where you need to be, where you have choice and control to live your life to the fullest.” Anything that architects and designers can do to give people that sense of connectedness and purpose is a step forward in the pursuit of happiness.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.