July 31, 2023

Chris Laing Builds a Bridge Between Architecture and the Deaf Community

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself, your background, and experience?

I grew up in Mitcham, South London, as the only Deaf person in a hearing family. My mum found out I was deaf when I was a few months old, and she started learning British Sign Language (BSL) so that we could communicate. As a young person, I didn’t have an awareness of barriers; at primary school I was part of a Deaf unit and didn’t yet understand the differences between me and my hearing peers.

Being Deaf, I found that I was always very visually minded. I was about eight years old when I knew I wanted to design buildings and rooms for a living, but I didn’t know the word “architect.“ I remember my stepdad once asked me if I would draw a new house for them. My step dad didn’t know any sign language so these drawings we shared together was our way of communicating. As I handed over these drawings to him, he saw the passion that I had, and he bought me some 3D software—and my skills and passion grew from there.

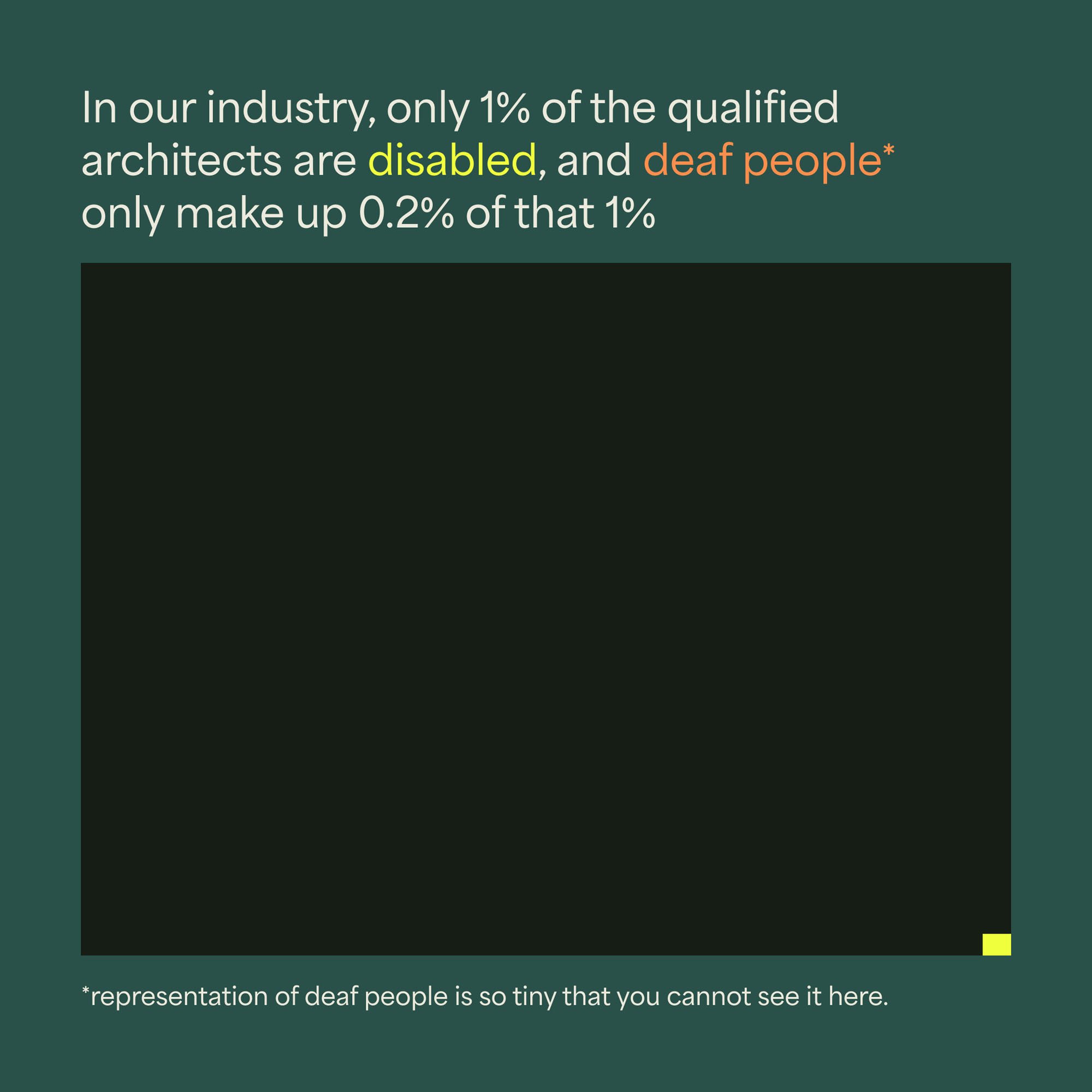

It wasn’t until I was older that I began to fully understand the obstacles I faced as a deaf person. With no Black Deaf architects visible anywhere in the UK, becoming one seemed like an impossible ambition, and it almost was. The academic qualifications required to get an architecture degree seemed unattainable for a Deaf person like me, for whom English is a second language, so I studied interior architecture and design instead.

This was the first time I became fully immersed into the hearing world, and it was a real culture shock. It was a learning curve to realise that I needed interpreters, notetakers, and teacher of the deaf (ToD), who would work with me one-to-one on my assignments to ensure I was getting full access to the course content. All of this, on top of the course itself and learning to fit into a hearing environment, was a huge challenge.

After completing the course I spent a year adrift and disconnected, not knowing what to do, until I met a Deaf architect with a mixed ethnic background. This, coupled with encouragement from my mum, gave me a new sense of possibility, and was instrumental in my enrollment in a full architecture degree program at Kingston University. This led to an MA at Royal University of the Arts, and a position with Howarth Tompkins architects, the firm where I work today. That journey has been far from easy, I almost gave up several times, and the problems I have encountered both in architecture and architectural education have led to the formation of the Deaf Architecture Front.

When and how did you conceive of the idea for Deaf Architecture Front?

I founded DAF to address the barriers and obstacles that stand in the way of people like me pursuing architectural careers. Over the course of my own journey, I had struggled to source interpreters and access resources, to secure work placements and find role models, to fight for funding—to see and believe that an architectural career might be possible. I want to be sure that things are easier for those who follow in my footsteps.

The idea for DAF really took shape in the wake of the BLM movement, when the world was starting to focus properly on systemic and intersectional injustices, and issues of access and inclusion became more widely understood. I took inspiration from Future Architects Front—a grassroots group founded to end exploitation in the architecture industry—which helped me understand that creating a unifying platform for the Deaf community in spatial design was the first, essential step in effecting change.

What are some of the barriers that prevent Deaf people from engaging with the built environment/architectural practice?

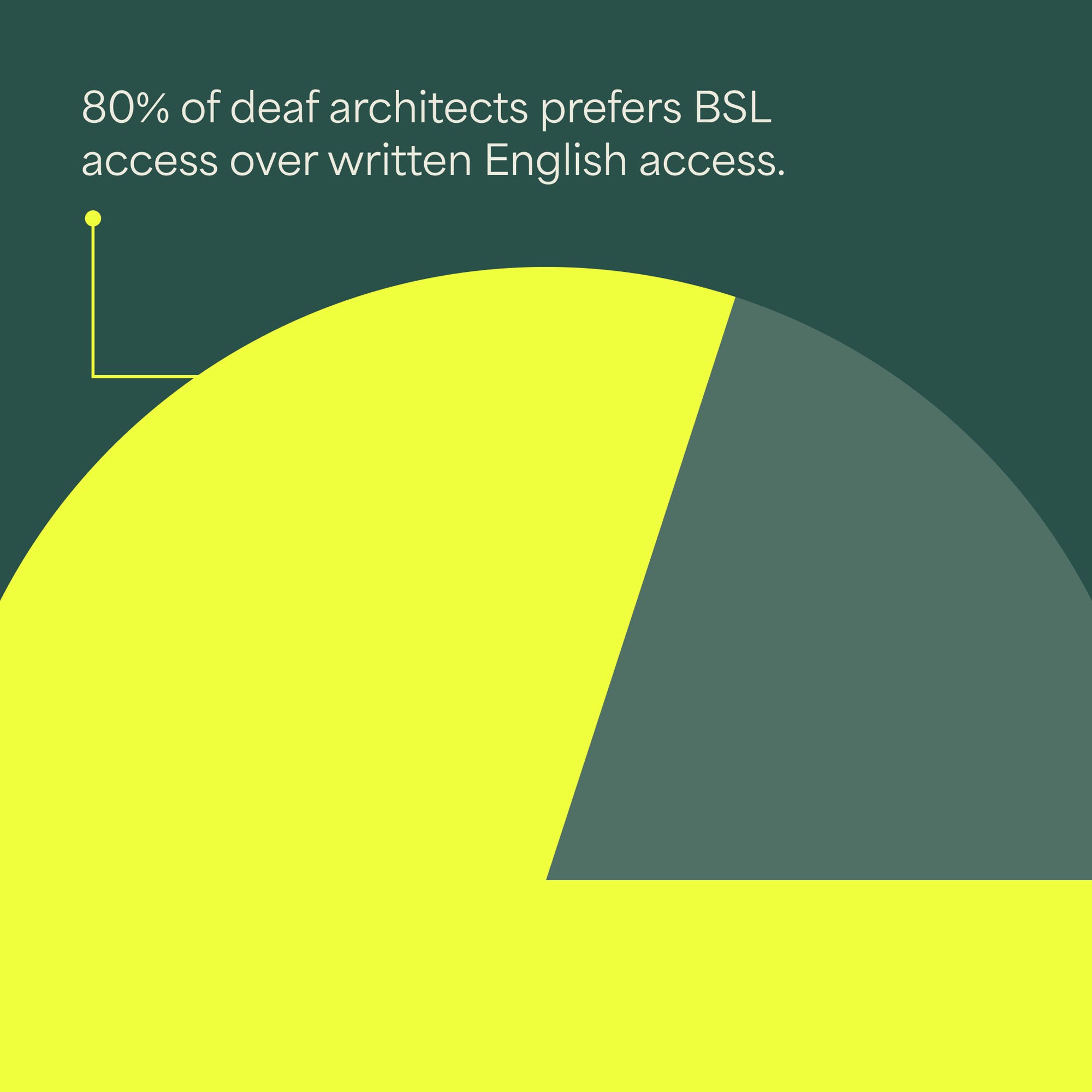

There are many and varied barriers! For me, one of the biggest is the fact that architectural education is heavily dependent on spoken and written English, which for Deaf people who communicate primarily in BSAL (or ASL), presents a barrier to accessing information in our first language. For example, I have not yet completed my Part III exam, as I am campaigning for the right to take it in BSL. Navigating websites can be a particular challenge for many Deaf people, and things like software training, which are normally conducted by someone orally explaining how to use a piece of software to a class of students at computer workstations, are difficult to interpret as they demand a Deaf person apply visual attention in two directions at once.

Sourcing and booking interpreters is another major challenge—there are only 1,800 registered BSL interpreters across the whole of the UK, so this isn’t just a problem in education; the lack of interpretation facilities often prevents or deters Deaf people from being involved in public consultations or events, so building projects go ahead without their input.

Can you talk a bit about Signstrokes and the limitations (or nonexistence) of BSL architectural terms?

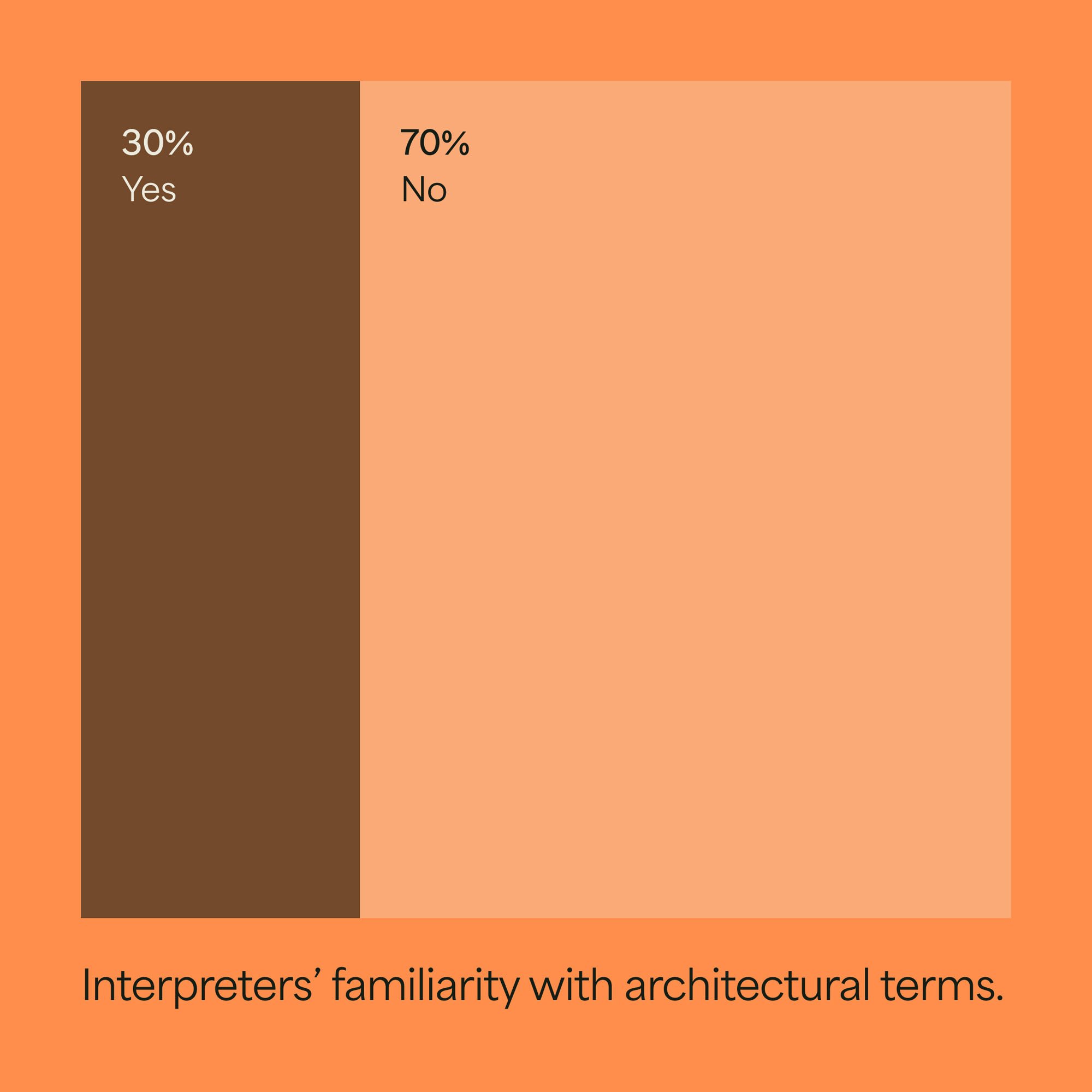

Throughout my studies, I tried to find signs for the technical language used in architecture—I would ask interpreters, and they simply didn’t know of any. I was therefore having to create architecture-specific signs on the fly, in parallel with my learning, which, as you can imagine, was challenging.

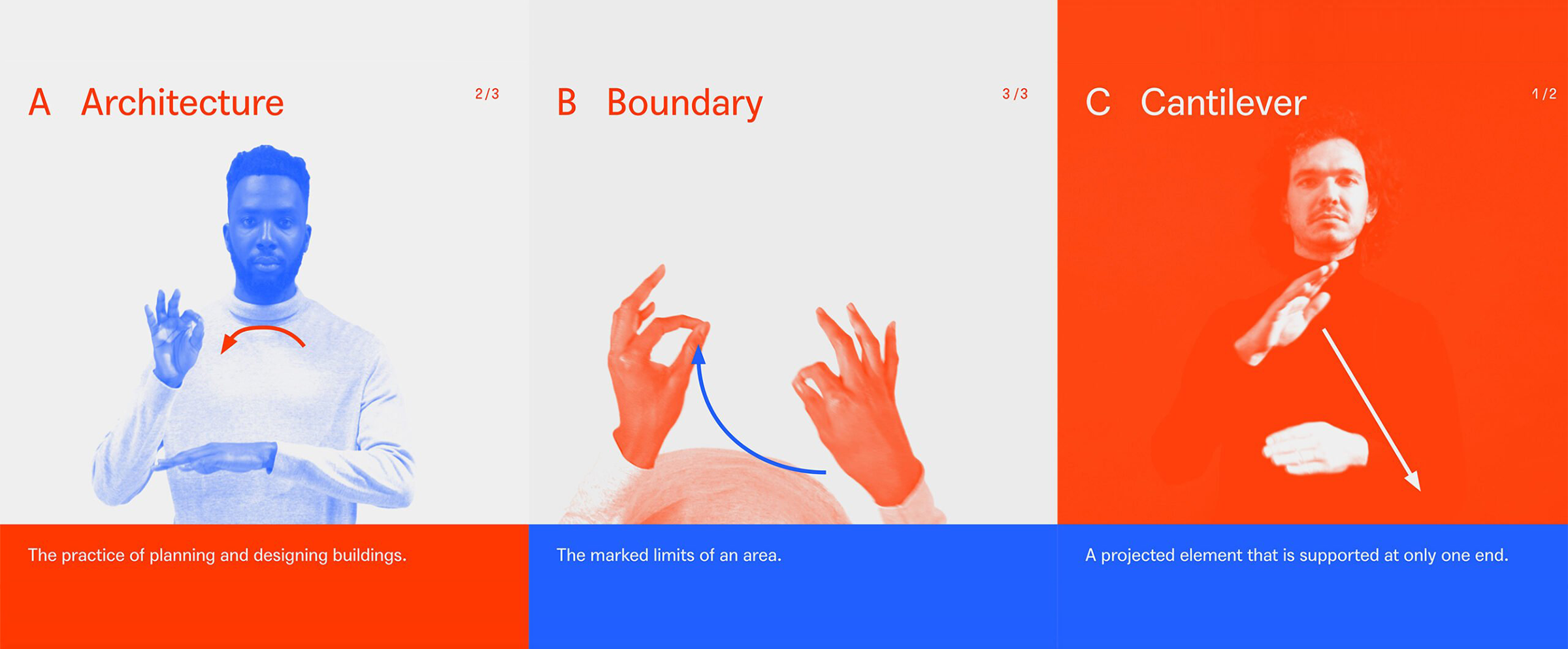

Adolfs Kristapsons and I developed Signstrokes to address the fact that BSL did not have any signs for architecture-specific terms—creating a huge language gap for Deaf architecture professionals and interpreters alike. The result is an ever-growing BSL lexicon for built environment and spatial design terminology—a much-needed resource that helps break down barriers to information. It is now part of DAF’s remit.

The Architectural Terms Competitions is a sweepstake-based initiative that enables people to raise funds for the DAF while also spreading awareness of the kind of architectural terms that Signstrokes set out to translate into BSL. To participate, you download a competition card from deafarchitecturefront.com/competition, and offer friends, family, or colleagues the chance to ‘buy’ one of the 15 words on the card for £5 or £10 each (depending on the size of sweepstake you choose). When the card is complete, you get access to DAF’s online raffle generator, which determines your winner. They win a third of the takings, while the rest goes towards supporting DAF at this crucial early stage in our operations.

How will DAF address the issues and raise awareness around Deafness and architecture?

DAF’s primary goals are interrelated: to generate awareness and proliferation of Deaf-friendly public space, and to break down the professional and educational barriers that keep Deaf people out of architectural careers. Put simply, more Deaf architects = more Deaf-inclusive architecture.

We aim to achieve this by offering a support network and safe spaces to Deaf people working in—or aspiring to work in—architecture; enhancing the visibility of practicing Deaf architects and designers; funding BSL interpreters, expanding Signstrokes; campaigning for accessibility guidelines to incorporate DeafSpace principles; and building a network of Deaf Consultants, who can advise architects and developers and ensure Deaf perspectives are considered in the architecture of the future.

Can you give an example of some of the most unfriendly public spaces for the Deaf community?

Many of the problems that a lot of public spaces present to Deaf people are not things that hearing people are likely to consider. Corners for example. A hearing person, whether conscious of it or not, is always assessing the space they’re in for changes. They know by the sound of footsteps if someone is about to turn the corner and can slow down or move to avoid a collision. Deaf people find themselves bumping into others a lot more often—something which can be mitigated simply by rounding off the corners.

Rectangular tables pose another kind of problem—especially for lip readers, who rely on full-face visibility. A round-table eliminates the issue. Lighting also affects communication—often when we go out, to a bar, maybe, my friends and I have to request a lamp so we can communicate with each other via BSL—there are times we’ve been refused and have had to converse by the light of our smartphones.

And then there’s public toilets. If you’re a Deaf person using a public toilet when a fire alarm goes off, how do you know? Without seeing people moving to evacuate, you might never realize an emergency is underway. Or if an elevator breaks down, what happens when we press the intercom button? I don’t believe that Deaf people should have to experience these kinds of anxieties in public buildings. It is my hope that DAF’s work will mean they never have to.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Viewpoints

Embracing Differences: Understanding and Designing for Neurodiversity

When we design for neurodiversity—be it autism, ADHD, sensory processing disorder—we design for everyone.

Viewpoints

David Gissen on Constructing an Architecture of Disability

The designer, historian, and educator speaks with Metropolis about his new book and the importance of centering disability in design practice and education.

Viewpoints

Manhattan’s Center for Architecture Imagines the Future of Universal Design

Curated by Barry Bergdoll and Juliana Barton, Reset: Towards a New Commons explores “more holistic approaches to inclusion” through architecture and design.