November 14, 2023

Embracing Differences: Understanding and Designing for Neurodiversity

What is Neurodiversity?

Coined by sociologist Judy Singer in the 1990s, the term “neurodiversity” challenges the notion of a singular norm and celebrates the natural variability in human neurology—including conditions like autism, ADHD and sensory processing disorders—as well as physical differences. As we become more educated on creating inclusive spaces that embrace all abilities, designers and architects are increasingly advocating for adjustments that improve focus, productivity, and comfort in settings like schools, workplaces, and beyond.

Learn more about neurodiversity and its crossover with architecture and design:

Neurodiversity

What is Autism and How Do We Design for It?

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurological development disorder that not only affects how people interact with others, but can also impact how they communicate and behave. About 1 in 54 children has ASD, and an even broader segment of the population identifies as neurodivergent. The A&D industry has responded, shifting away from designing for the “average” person and embracing a more universal approach that accommodates a greater range of thinking styles. Designers have also stepped up to the plate creating everything from colorful kitchen tools and human-centered spaces to inclusive nonprofits and evidence-based design guidelines to address built environments for those on the autism spectrum.

To learn more about how we can design for autism, check out the following articles below:

Autism

What is Sensory Design?

As mentioned in Ellen Lupton and Andrea Lipps’ book The Senses: Design Beyond Vision, which accompanied the eponymous Cooper Hewitt exhibit in 2018, sensory design addresses how people receive information and explore the world. It is manifested through the sense of touch, sound, smell and taste. Though the topic has only recently entered popular discourse, sensory design has expanded to include a mindset shift in how we can create spaces for all people, regardless of their sensory abilities. This, we found, helps better connect us to the material world and to each other.

For a closer look at sensory design, check out the following articles:

Sensory Design

How Can We Achieve Accessibility and Universal Design?

In the realm of design, accessibility entails creating products, devices, services or environments that can be used by as many people as possible. Though discussions around the topic have been ongoing for a while, a turning point in the conversation occurred when the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed in 1990. The landmark legislation not only outlawed discrimination based on disability but also required employers to provide reasonable accommodations to employees with disabilities and enforced accessibility requirements on public accommodations. More than 30 years later, great strides in accessibility for architecture and design have been made, but there’s still much work to be done—especially in the technological and the building space.

Read more about how we can design for accessibility and universal design with these articles.

Accessibility

Conclusion

By taking steps to foster independence and empower success for those with neurological differences, examples of truly accessible architecture continue to grow. Architects and designers are increasingly weighing concepts like acoustics, spatial sequences, and sensory zoning that encompass design elements like color, lighting, material choices, wayfinding, and technology. As the notion of designing for neurodiversity continues to evolve our ideas of inclusivity and accessibility, we can agree on this: There’s a growing aspiration for creating more inclusive environments where diverse minds and abilities harmoniously coexist.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

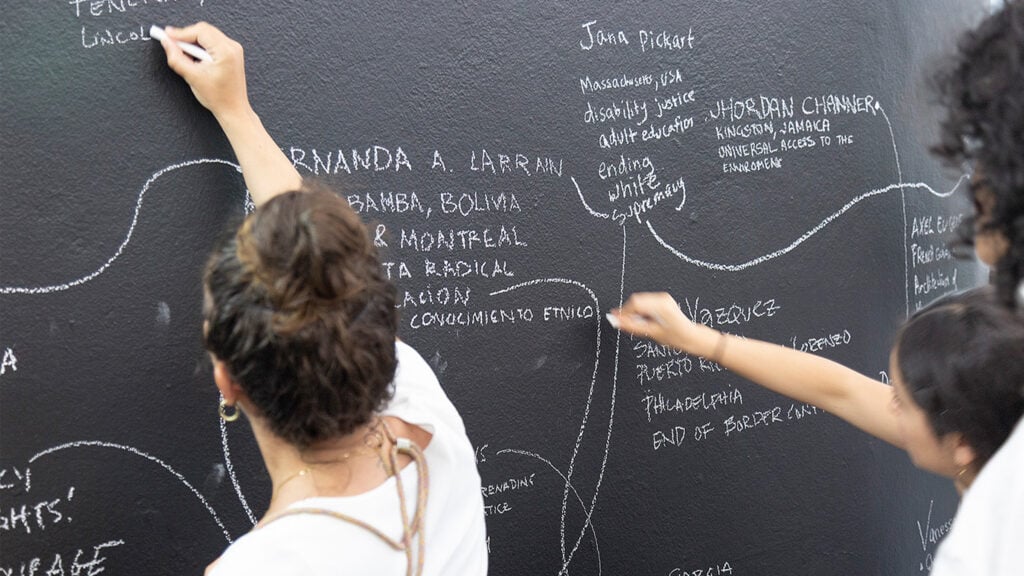

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.

Profiles

The Next Generation Is Designing With Nature in Mind

Three METROPOLIS Future100 creators are looking to the world around them for inspiration.