May 15, 2020

Already Great: Successful Civic Architecture Begins at the Municipal Level

While federal architecture dithers over style wars, civic projects at the city, county, and state-level march to the beat of a different drum.

In February, a draft executive order from the White House surfaced, which threatened to mandate that all new federal buildings be designed in neoclassical or traditional regional styles. Titled “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again,” the order proposed a revision of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1962 “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture” and a possible ban on Brutalist and Deconstructivist styles, which were specifically noted. While it’s unclear whether the order will ever be implemented, it predictably ruffled feathers in the architecture world and was denounced by a slew of professional organizations, including the National Organization of Minority Architects, the American Institute of Architects, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the American Society of Landscape Architects.

But the most exciting by-product of the controversy wasn’t the advancement of a compelling argument against a mandated style: It was a realization that individual states and cities are already commissioning buildings that reflect their constituents’ expectations of pluralistic and progressive architecture—regardless of the Trump administration’s mood in Washington, D.C.

For proof, look to current practice and consider what is being built. Public buildings can tell a region’s story. A good analogy might be politics: Local elections are often less susceptible to the political theater of the national news cycle and ideological grandstanding at the federal level, which nonetheless captures our attention and imagination; and local results have a greater impact on our daily lives. Likewise, local architecture must chart a realistic, pragmatic course to serve the specific needs of its community.

So where can we discern government projects that represent their local communities and lead the march toward a more progressive architecture? Consider those designs that speak to prevailing ideals of our time, such as community, social justice, government transparency, sustainability, and cultural sensitivity.

Police community relations are one national issue with intensely local consequences. And justice-reform experts suggest that building a community-led policing strategy (one that addresses public safety concerns, advances social equity, and fosters trust and familiarity between officers and residents) should extend to the design of the station itself. To that end, Minneapolis-based firm Snow Kreilich designed the local Metro Transit Police Department to serve as an expression of the community-policing philosophy.

Completed in 2019, the project included a renovation of and an extension to an existing building, fronted by a parking lot and flanked by a main entrance. Rather than design a defensive, fortified station with clerestory windows, as is often the case, the architects opted for floor-to-ceiling glass and conceived an inviting main entrance on a street-facing elevation, now used by both the officers and the public.

“How do you make a building that is safe and secure, but doesn’t feel like a bunker?” Matt Kreilich, a founder of Snow Kreilich, asked rhetorically. Then he added: “The vast majority of interactions at this building are positive, so how do we make it a pleasant experience?” Rather than bulletproof glass, a receptionist in a welcoming lobby greets visitors, with layers of security beyond. Establishing a common entrance and incorporating a view of the lively social scene, including neighborhood breweries, music venues, and public transit, helped the station assert a message of trust through its building connections.

That approach has precedent. The search for open and inviting municipal architecture propelled the great Brutalist government buildings of the 1960s and ’70s, most notably Paul Rudolph’s Government Service Center in Boston, where a mostly glass facade signifies openness and transparency. While the metaphor of transparency does not necessarily carry over into government, such features can offer clearer wayfinding and more accessible navigation.

Another inclusive design is that of the East County Office & Archives in Santee, California, where architecture firm Miller Hull devised what it calls “the public street.” It is basically a main corridor—covered by a folded roof and daylit from above by a long clerestory—that was built to provide a friendly link between the entrance and services inside. Like storefronts on a familiar main street, the county clerk, tax assessor, and county archives are all arranged along the corridor for intuitive navigation. “Transparency and clarity are attributes critical to wayfinding, but also represent the ideals of an accessible government in service to its community,” says Ben Dalton, a principal at Miller Hull.

While embodying larger ideals of good governance, such as community building and accessibility, progressive municipal architecture can also reflect local context in a way institutions cannot.

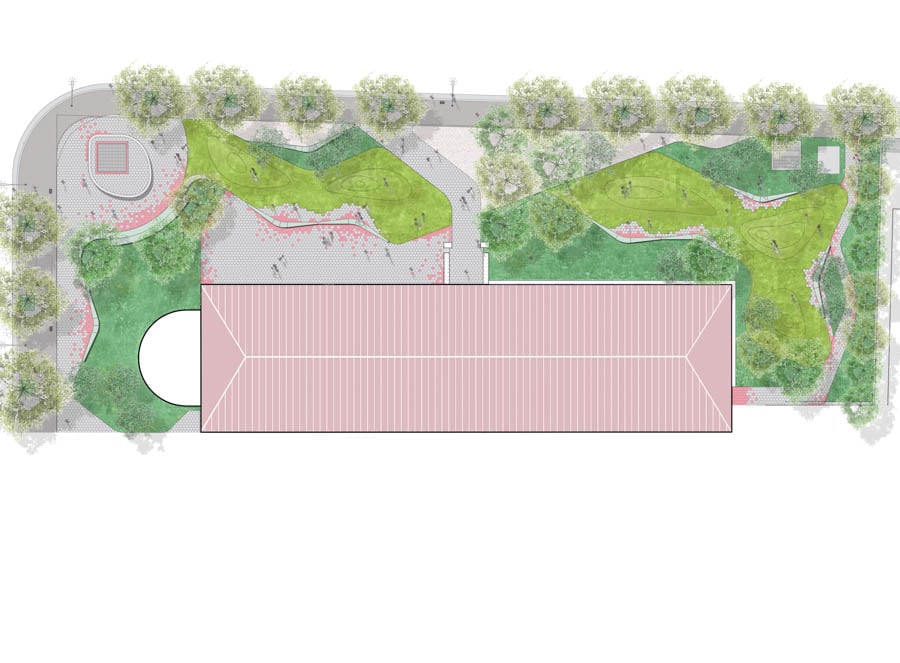

In Culver City, California, wHY Architecture has designed the landscape for an existing neo-mission-style courthouse using native-species plantings that respond to drought conditions notorious for killing the area’s lawns. Native plants such as salvia, alumroot, Little Sur coffeeberry, ceanothus, silver bush lupine, and sand dune sedge need less irrigation and blend naturally into the surrounding hillsides, improving water usage as well as adding visual interest to the site.

The landscaping acts as a connective tissue, binding the property to its surrounding streetscape. “We asked, what does it mean to have a city hall?” said Mark Thomann, a director at wHY. “It has to be civic and inviting, with layers of garden and open space.” Linking Culver Boulevard’s robust pedestrian traffic with the adjacent residential neighborhood, the landscaping responds to its context: It serves as a flexible, open space attuned to the site conditions.

A civic building should also meet the needs of those who work in it. Many newer public buildings excel in energy efficiency, which translates into comfortable working environments featuring daylighting, passive ventilation, and natural materials. As a demonstration of Santa Monica’s reputation as a progressive city, building performance and wellness were a main focus for Frederick Fisher and Partners (FF&P) as they designed the Santa Monica City Services Building.

Working alongside Living Building consultants from engineering firm BuroHappold, FF&P united all of the city’s services in one state-of-the-art facility annexed to city hall. Foregrounding sustainability and a healthy workplace, the new volume sets a standard for energy and water performance in public buildings and aspires to goals of carbon neutrality, water self-sufficiency, and zero waste in the future.

From the conceptual stage, the building’s energy efficiency informed the design, starting with a decision to orient the building in a way that maximizes natural ventilation to cool its concrete slabs at night. The massing is long and narrow, so daylight floods most of the open-plan workspaces; meeting rooms occupy the parts that are farthest from the windows. Radiant heating and high-performance glazing, among other moves, helped to earn the project a net-zero-energy designation. Meanwhile, composting toilets, gray-water irrigation for landscaping, and a backup well for use during drought conditions help curb water consumption.

“Rather than celebrate the building as an icon, we hope it is an expression of values about civic government that embodies what the creative community of Santa Monica is about,” FF&P partner Frederick Fisher says.

Community representation is something many cities rightfully demand of civic architecture, and firms are aware of the expectations. “Design is such a diverse field,” says Brian Tibbs, a partner at the Nashville office of Moody Nolan, architect of record on the Corgan-designed Terminal Garage and Airport Administration Building for the Metropolitan Nashville Airport Authority, expected to be completed this year. “To say that everything has to be one way is really boxing us in; it’s definitely not symbolic of the design community.”

Not only is it socially dubious to mandate one style, it’s politically incorrect. These projects and their architects show that sticking to any one style misses the point of America’s public spaces. Moynihan, in the original “Guiding Principles,” wrote, “The Government should be willing to pay some additional cost to avoid excessive uniformity in design of Federal buildings.” Whether classical or modern, the style matters only to the extent that it ensures the building evokes an appropriate sense of place. Followed to the letter, that guidance could lead to a traditional profile as easily as to a modern or contemporary one.

For Robert A.M. Stern Architects, the appropriate scheme for the Nathan Deal Judicial Center (NDJC), Atlanta’s state courthouse dedicated in February, incorporates both contemporary and classical elements. A monumental curved facade is an expression of a civic tradition in America and in the history of Georgia’s courthouse buildings, many of which are neoclassical in style. However, the building and its civic ambitions still have much in common with progressive, contemporary projects because it also features a welcoming entry and interiors, friendly wayfinding features, and transparency—though not in the ways one might guess. Large windows on the third and sixth floors open to views of the Georgia state capitol, connecting the building visually to the political core across a highway.

“Though the Nathan Deal Judicial Center looks like a classical building, it is in fact completely modern—essentially an office building with court suites,” says Grant F. Marani, a partner at the firm. “Our design emphasized wayfinding, a consideration that challenges many Modernist buildings. Our main entrance, behind a plaza, is easy to spot. Once inside, the atrium provides even first-time visitors with an immediate sense of the building’s organization.”

In other words, the NDJC may take cues from national political theater, but it ultimately has its own agenda, which is more attuned to context and responds in specific ways to local community needs. To be sure, more projects that embrace such needs are on the drawing boards and continue to be built by municipal, county, and state governments. As long as Americans continue to act locally, they’ll continue to fuel this blueprint for future civic pride. All the better to represent a multitude of places and demographics, rather than a one-size fits-all solution.

You may also enjoy “New Talent: Space Popular Mines the Distant Past and Imminent Future“

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.