April 24, 2023

Confronting Carbon Form, Embodied Carbon’s Complex Cousin

You won’t encounter any recent discussion of sustainable design without mention of embodied carbon, and that’s exactly as it should be. To grapple with the embodied carbon of a building means to take into account all of the greenhouse emissions produced by the manufacture, transport, and installation of building materials. Where the concept falls short, according to Elisa Iturbe, assistant professor at the Cooper Union, is that the quantification of carbon sometimes leads us to “neglect to understand that what is also at stake is this vast interconnected network of spaces and that in itself is a carbon form.” The trees are important, but we can’t ignore the forest.

Confronting Carbon Form

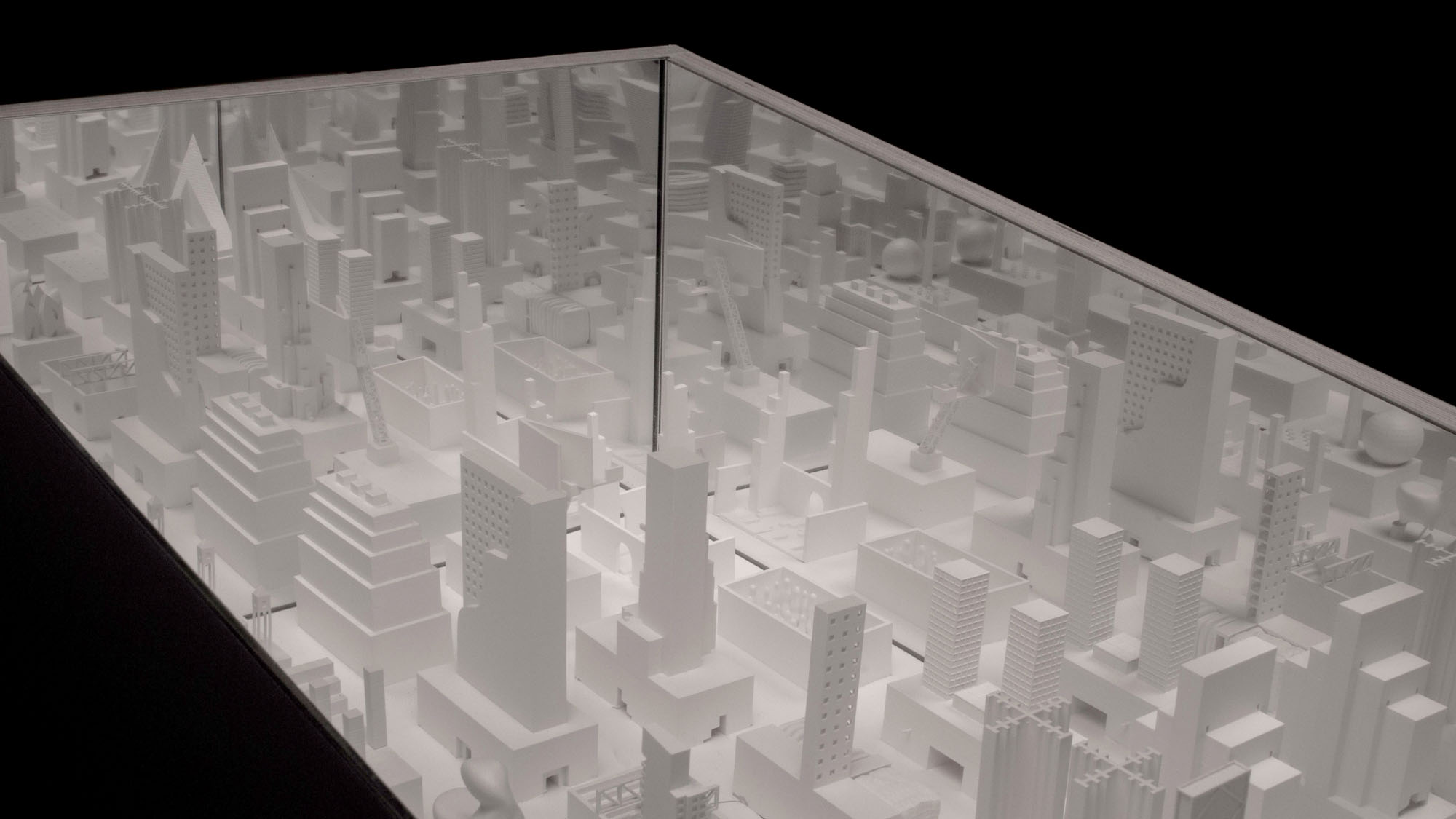

Confronting Carbon Form, a recent exhibition curated by Iturbe, Stanley Cho, founder of architecture practice Outside Development, and Alican Taylan, a Ph.D. student in architectural history at Columbia University, that was on display earlier this month at the Cooper Union takes a wider conceptual vantagepoint by examining carbon form and the broader landscapes of extraction.

The exhibition posits that what’s at stake is not simply the carbon required to produce an individual building but the carbon required to produce everything that comes into that building and to transport every person and every thing that might come into it.

“Our current conception of the city is completely dependent on production happening outside of the city; all of our spatial organizations are dependent on commodity production elsewhere and distribution aloof, which is super energy intensive,” Iturbe remarks.

Carbon Form and City Planning

Much of the exhibit was dedicated to paintings and graphics of well-known planning schemes, structures, and maps presented in simplified colorful silhouettes. Suburban forms that presume effortless automobile circulation are an obvious and familiar iteration of carbon form. The exhibition featured plans and renderings of Linear Cities and the Ville Radieuse that are stripped of their finer details to provide a vision of endlessly replicable construction.

The urban grid is healthier but part of the same continuum. The exhibition wall text explained, “An unbounded grid offers unlimited growth, which in turn perpetuates our current energy paradigm.” Their point is reemphasized in another segment which presents familiar planning templates, such as Koolhaas and Vriesendorp’s City of the Captive Globe in mirrored frames; the whole carbon-ravenous aim is not just to build them once but to build them over and over again.

A Problem of Scale

Distance is perhaps the most defining feature of these carbon forms. While a factory or warehouse or power plant might have been down the street in 1900, today it may be thousands of miles away, and the connecting tissue is yet more carbon use in the form of transportation networks. The world is increasingly composed, as the exhibition text read, of “highly specialized environments that can only function because of infrastructural integration at the territorial scale.”

Several Soviet examples complicate the picture of extractivism as a uniquely capitalist problem. “Part of the argument is that carbon modernity is an epistem that is continuous across different political ideologies and moments of historical rupture,” says Iturbe.

The Carbon Consequence of Everyday Objects

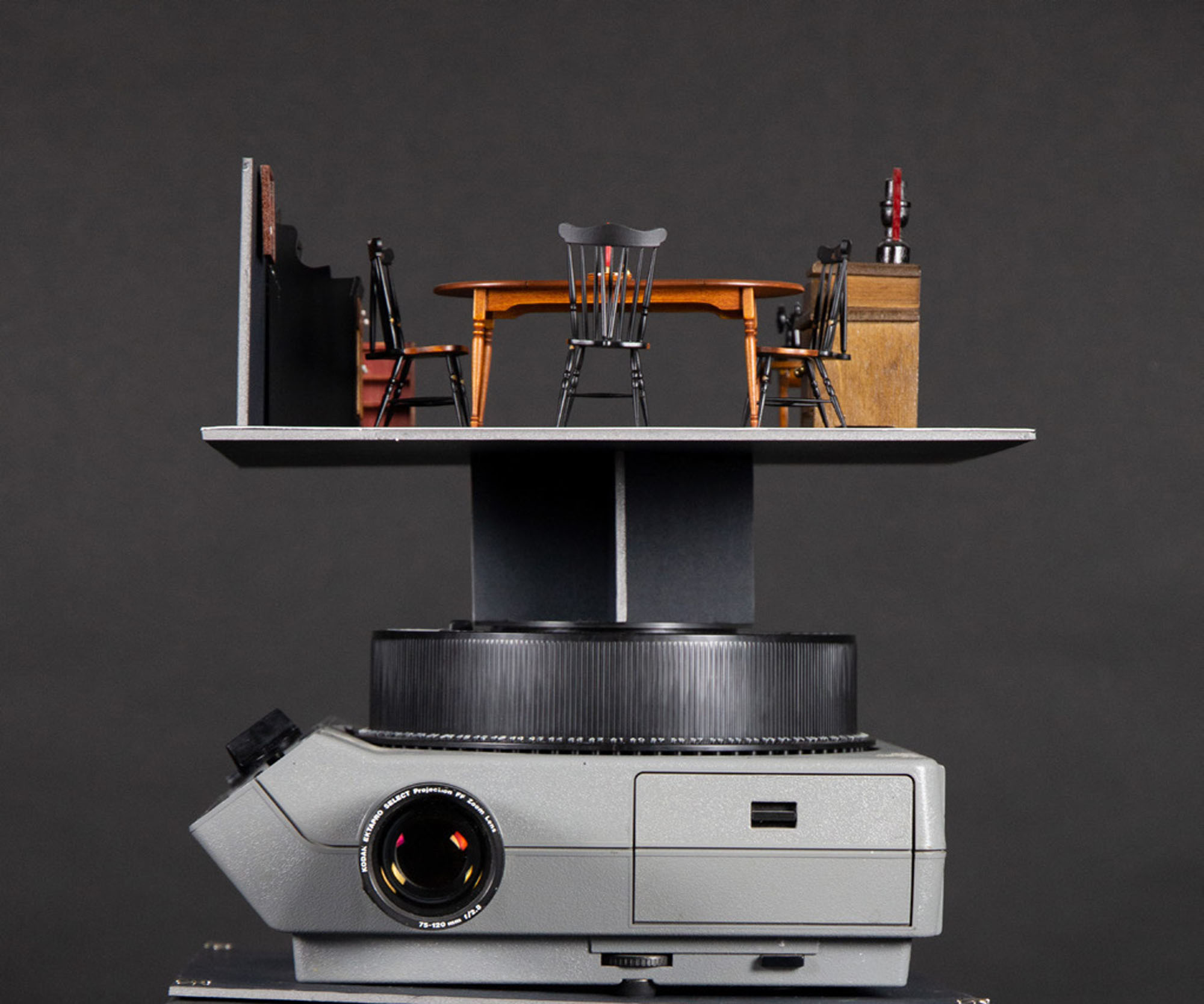

Some of their curatorial methods are ingenious. The Carousel of Progress exhibit, which Walt Disney designed for General Electric at the 1964 New York World’s Fair was the starting frame for a slideshow included in the exhibition. The slides presented images of the vast landscapes that are necessary for the production of domestic furnishings that appeared in the original exhibit. Taylan recounted, “Every time we picked one domestic object, we would look at the multiplicity of spaces that are required to have that one object to exist by itself.”

A chair, for example, might seem simple enough, but its production requires an extensive geography of specialized landscapes; slides for this range from lumber camps to Ikea factories. A washing machine, meanwhile, featured slides of coal, copper, and bauxite mines; water infrastructure; manufacturing plants; and the scrap metal and appliance graveyards that these processes generate after use.

What To Do About Carbon Form?

The exhibition featured one foray beyond diagnosis and into prescription, Iturbe explains, “When the city doesn’t offer spaces in which we can make things for ourselves then we become more dependent on production.” These solutions are efforts to break the cycles of production and shipping that intrinsically entail huge networks of production and shipping. One example Iturbe proposes is as simple as installing enhanced facilities at a fisherman’s pier. Amenities like countertops, sinks, lockers might be of use to individuals and to restaurants or other small-scale businesses—and spare the need to buy items whose production footprint might well stretch hundreds or thousands of miles.

Humanity’s deep indebtedness to carbon form is like a bank account whose balance we never check and investigating it is fascinating and though-provoking work. Though the exhibition was short on prescriptions, it is be credited for a cogent diagnosis, carbon form, the curators posit is “a source of energy that exists outside of the living biospheres and as such creates the illusion of autonomy from humankind’s immediate ecological dependencies,” this is a diagnosis that requires immediate attention.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Profiles

BLDUS Brings a ‘Farm-to-Shelter’ Approach to American Design

The Washington D.C.–based firm BLDUS is imagining a new American vernacular through natural materials and thoughtful placemaking.

Viewpoints

How Do You Measure a Product’s Sustainability?

Global head of sustainability and impact for the iF Design Awards, Lisa Gralnek, discusses the challenges of evaluating sustainability across diverse design disciplines.

Viewpoints

What ThinkLab is Hearing: Inside the Tariff Turmoil

Discover unfiltered insights from industry leaders, revealing how tariffs are reshaping strategy, pricing, and partnerships.