May 10, 2023

Does Parking Explain the American City?

Henry Grabar, a staff writer at Slate whose reporting focuses on urbanism and design, believes that nothing explains the built form of today’s cities quite like parking. His new book, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World (Penguin Random House), dives into every aspect of this seemly quotidian subject: from the mandatory parking minimums that drive up the cost of affordable housing and make dense neighborhoods illegal to build, to the physical altercations over who can park where that break out with shocking regularity in American neighborhoods. Throughout the book, Grabar shows how much of the 20th-century’s built environment was determined not so much by where people drive, but where they can find a place to park. In order to right the wrongs of the past, he argues, we’ll need to reexamine this unloved backwater of urban planning.

Parking Is at the Core of Everything We’re Trying to Do in Cities

Ethan Tucker: The other day I was telling an architect that I was reading this book about parking, and they were like, “How boring. Why would you read a book about parking?” Obviously, you don’t think parking is a boring subject. What led you to pursue this topic and why should designers pay more attention to parking?

Henry Grabar: I am a journalist at Slate who writes about cities and in topic after topic that I came across, whether it was housing affordability or flooding or transportation from bus lanes to bike lanes or even municipal finance and revenue-driven policing, parking kept coming up as this subject that was absolutely at the core of all these things. I thought, well, I should try and knit all these subjects together and explain how parking and our fixation on parking, which I think is a broader psychological issue, is at the core of so many of these other things we’re trying to accomplish in our cities.

ET: You mentioned that parking has become this psychological fixation, what you mean by that? How has it become this thing people get really worked up about and even get into fights over?

HG: Well, I think that parking is really messy, right? The rules of the road are what they are, and they’re the same in every place you go. And so, if you know how to drive, I feel like you can pretty much feel at home in any city or state you drive into, and even in foreign countries as well. And when it comes to parking, it’s just such a different scenario. You go into a new place and the parking rules are totally inscrutable.

That’s because parking is basically this mismanaged and ignored backwater in urban planning where we’ve decided to have a bunch of overlapping and conflicting systems that make no sense. And so, this breeds confusion and in the case of parking fights, contested systems or expectations of ownership is something that I see all the time with parking. People believe that public parking to some extent is private property if it’s in front of their house, or their shop, or even just in their neighborhood.

So all these factors together, it doesn’t surprise me much that people wind up fighting about it. And the other thing I’ll say about that is that obviously people don’t fight about parking because they place a particular importance on parking. It’s just that parking is a means to an end. And unfortunately, throughout most of this country you need to drive to do most things. And so, parking is the link, parking is access, parking is your ability to do the thing that you got in the car to do. And so, I understand why it makes people emotional.

Parking Imposes Suburbanization, Not the Other Way Around

ET: That’s definitely the experience of parking in New York City, which is pretty unique among American cities for its lack of parking and lack of driving. Do you want to just briefly touch on how parking has determined the shape of some other cities, especially Los Angeles, and cities in Texas and Florida?

HG: In most jurisdictions in the United States, parking is a required feature of any new building or renovated historic building that’s taking on a new use. And there are these incredibly precise and complicated documents that determine how many parking spaces need to accompany, for example, a nunnery or a public swimming pool, or an apartment building, or a restaurant, and so on. And typically, the number of parking spaces required is very high.

As a result, parking becomes a very important, in fact, perhaps it’s the first thing that as an architect or a developer, you need to figure out when you get a site.

I think that if you look at cities that have evolved and continue to grow as these parking requirements were imposed, like Los Angeles is the example that I talk about in the book. You can see the architecture of the buildings evolving with the increased parking requirements as older forms of development basically go by the wayside because it is impossible to build them anymore.

And with the newly required number of parking spaces, I think people complain all the time about how they find new development is bigger and boxier, and uglier and unpleasant, and why don’t we build it like we used to? The answer to that question is pretty simple. It’s illegal to build it like we used to. Look at a new building in downtown, look at a new condo building in Austin or something like that. It’s like literally half a parking garage and the condo’s on top like that.

ET: And those minimums, as you point out in the book, they’re basically based on nothing, right? They were drawn up out of thin air and have just been perpetuated ever since.

HG: Yeah, they are based on some very limited data sets and in cases comically limited, but I think the most important thing to know about them is that they are based on examples taken from the suburbs. And so, when you take those suburban land use patterns and you make them a part of the city code, you are essentially telling architects and builders who are building in a place that’s not supposed to be car dependent to build all their structures as if they were operating in an entirely car dependent sprawling suburbs.

And so, these parking minimums became a way for cities to impose suburbanization on their own built fabric. And you can understand the attraction for them, right? They were struggling with congested curbs and people double parking and circling and looking for parking. And they thought, “Well, why don’t we make the private sector take care of this instead of us building the garages will require that every single new development, it builds the parking for us?”

In the 50 years since, it’s changed the way buildings look and the way neighborhoods feel. And anybody who’s ever walked around on an arterial road on the outskirts of an American city can tell you that what you’re mostly experiencing out there is the experience of walking through parking lots.

How Did Walkability Become a Luxury?

ET: One of my main responses to reading the book was just anger at this whole system that keeps us from building the cities that most people seem to want to live in because of parking. Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? Are there signs of change that maybe we’re moving away from this system of suburbanization?

HG: Yeah, I share your sense of irritation. One of the most profound and tragic misunderstandings to come out of this whole situation, when I say that I mean the American built environment broadly construed, is that places where it’s possible to walk have become very expensive because there are very few of them and they’re in great demand. And as a result, walkability, which you would think would be one of the most core elements of any human landscape has been taken as some sort of bourgeois amenity, and infrastructure or architecture that tries to make places more walkable is often misconstrued as an amenity for people high up on the income ladder, which doesn’t make any sense if you think about it.

And all of that is related to the fact that we have made it illegal and impossible to build more of those places. Often, the very same people, on the one hand will say, “We want a neighborhood like that. We want it to look like that.” But they refuse to make compromises on the question of parking. There have been a lot of studies that show that the amount of parking you provide determines the extent to which you’re going to wind up in a place where you’re able to walk. That’s not just because of the way the environment is designed, but it’s also because the more parking you have, the more you encourage people to drive and own cars.

However, I think there are lots of signs to be optimistic about. First, there’s a very vibrant and successful movement to repeal parking minimums in downtowns, around transit, for affordable housing development, and in some cases for entire cities. This movement has come to basically every corner of the United States, and it’s been really exciting to see these laws that for 60 years have deformed the American environment basically fall away over a period of five years as groups of activists like the people in the parking reform network go from city council to city council and make the argument.

The second aspect is that since the pandemic, and to some extent before, there’s been a recognition of how much valuable land at the curb has been given away to free storage of private automobiles. And people are starting to realize that that land could be put to other uses including bike lanes, bus lanes, or storm water retention, which is becoming a bigger and bigger issue with climate change—you can install, for example, bioswales or other types of landscape that will hold up rain and prevent urban flooding along the curb. And then of course with the pandemic, the idea that curb space could be used for restaurant seating or café seating or just public space. The parklet movement has been underway for 15 or 20 years now, but the pandemic really supercharged it.

Even if there’s been some backsliding since then, I feel optimistic that there’s been a widespread realization on the part of city dwellers that this is basically a waste of what in many places is the most valuable land in the city, the access point between the street and the building.

The place I’m feeling slightly less optimistic about is that I think that some of these changes, especially reducing parking minimums, people often talk about it with the understanding that this change will come with fewer people driving. And I see less evidence that people are going to stop driving. And I think to the extent we can build buildings with fewer parking spaces, or at least fewer required empty parking spaces that drive up the cost of housing, that’s great news. But it needs to be accompanied by changes to the streets so that people feel comfortable getting around without their cars. And on that front, I feel like the United States is way behind developed countries in Europe or Japan or China, where it’s just become an expectation that you can ride a bike without worrying about being killed. Unfortunately, that’s not the case even in the most walkable cities in this country.

Is There a Better Way to Park?

ET: What was the most surprising or interesting thing you learned about parking from reporting on the book?

HG: There’s been a lot of awareness in recent years about parking minimums as a force that propels architecture and urbanism into this low-density sprawl loop where everybody has to drive everywhere. But I think one thing that surprised me in learning about them is that one of the worst things about parking minimums is that the parking cannot be shared.

And if you think about it, sharing is at the root of so many of the efficiencies that cities unlock, which is to say certain facilities are used during the day and certain ones are used at night. And power generation is like electricity gets used by offices during the day and then it get used by homes at night. And that enables us to unlock basically all these. It’s just more efficient. It allows us to unlock a lot of savings associated with the provision of services and infrastructure. And with respect to parking, there’s an enormous potential there because there are so many compatible uses that are currently required to each have their own parking. But if they were just to share their parking, then you wouldn’t actually lose any parking in terms of access. Drivers would still basically have the same amount of parking available to them at various times of day. But in terms of the urban environment, you could almost cut the amount of parking required in half.

Another thing I realized is that for people who work with their cars (delivery, logistics, trades, etc.) the current parking-traffic status quo is pretty bad—parking may be free, but one box truck can rack up 10s of 1000s of dollars in tickets double-parking, because it’s impossible to find a legal space. Plus, the free parking-induced traffic adds huge costs for anyone who works with their car.

Also, better parking management doesn’t necessarily mean it gets more expensive to park—San Francisco’s SF Park reform raised rates on high-traffic streets, but garages got significantly cheaper, in an effort to push commuters into off-street parking. And on the whole, ticket revenue went down—to the extent out-of-towners find legal parking and pay meters instead of finding illegal parking and paying tickets, that’s a fairer system.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Projects

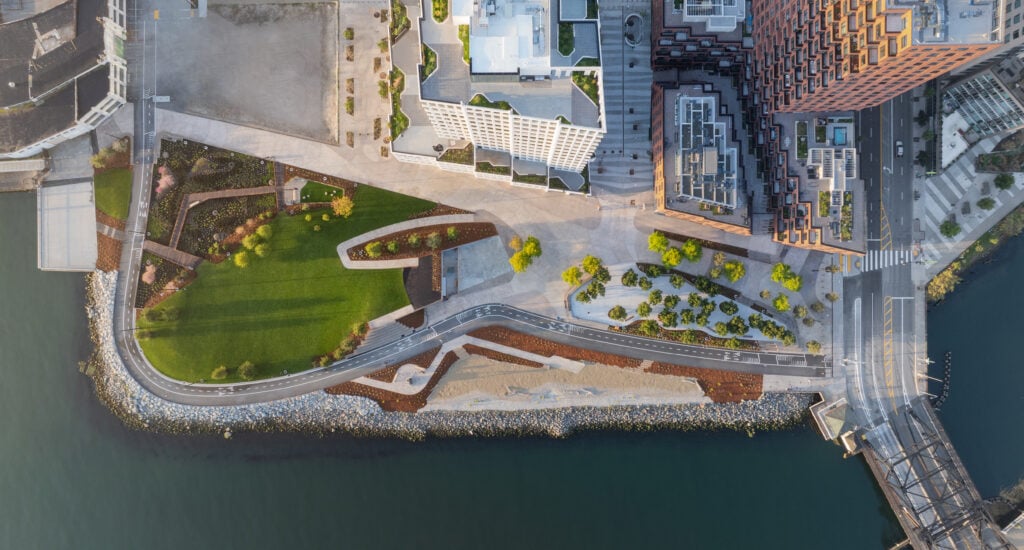

Mission Rock: San Francisco’s Waterfront Future

A Bold Vision Brings Resilient Parks, Affordable Housing, and Iconic Architecture to a Former Industrial Site.

Projects

Behind the Latest Megaproject to Rise Along Atlanta’s Beltline

Transforming an industrial wasteland into a vibrant mixed-use development, Fourth Ward is an ambitious addition to the city’s rapidly developing network of trails.

Projects

A ‘Ghost River’ Flows Through Baltimore

Learn how this public art installation tells the story of 100 years of urban development—and invites us to imagine what the next century should look like.