September 3, 2024

Behind the Latest Megaproject to Rise Along Atlanta’s Beltline

“You feel the echo of the past—that fascination with things that will never be built again.” – Jim Irwin, developer

An Ambitious Mixed-Use Development Along Atlanta’s Beltline

Just a few blocks away, his latest project, called Fourth Ward, is by far his most ambitious. The mixed-use development, sited on a former surface parking lot owned by Georgia Power, takes advantage of both the Beltline, to its east, and, to its west, Fourth Ward Historic Park, a new 17-acre facility that includes green space, playgrounds, an amphitheater, a skate park, and a 2-acre lake, which doubles as a retention pond. Fourth Ward now includes New York-based Morris Adjmi Architects’ stepped brick Overline Residences (2023) and diagrid concrete and glass Fourth Hotel (which just opened) as well as a one-acre central plaza by Brooklyn-based Future Green, with master planning by Perkins&Will. Like all of Irwin’s projects, it is head and shoulders more sophisticated than most of the generic new complexes rising around the rapidly developing Beltline, and much of Atlanta.

The 16-story, 196-room FORTH Hotel is arguably the most striking component of the development. Its robust facade, topping a three-story, gray brick podium, consists of a concrete diagrid fronting floor-to-ceiling windows. “We wanted to give it a clear identity,” says Morris Adjmi, who notes that the sharp diamond shapes also carve out dramatic views inside rooms. “You get that layer of the glass plane and the structure and the way the diagrid elements kiss each other in the corners,” he adds.

Eclectic interior public spaces—marrying cozy rustic and sleek midcentury—are textured with, among other elements, timber-clad ceilings, parquet flooring, antique rugs, bespoke furniture, and paintings and tapestries that depict mountains and forests. Four restaurants, not to mention a members club bar and lounge, provide several more moods and settings. Apartment-style suites, warmed and energized with oak flooring, earth tones, and floral wallpaper, feature several Adjmi-designed pieces, including bed frames, armoires, minibars, and bedside tables. Adjmi, who employs this kind of holistic approach whenever possible, describes the design as “Southern hospitality—something that feels warm and friendly and human—but at the same time alluding to travel, sophistication, and a little bit of adventure.”

The development’s centerpiece is a 1.1 million-square-foot, 11-story commercial high rise designed by Seattle firm Olson Kundig. The sleek black, metal-edged edifice, containing retail at its base and several levels of sub-surface parking, is two bridged masses, separated by a wide swath of sloping greenery (a collaboration with Future Green.) Irwin calls the stepped passageway, packed with local plantings and cooling water features, a “portal,” breaking down the project’s mass, actively connecting the Beltline to the Fourth Ward Park, and creating valuable, highly diverse public space. Olson Kundig principal Kirsten Ring Murray, who compares the portal to a verdant version of Rome’s Spanish Steps, notes that colleagues call it the “Appalachian Steps,” an homage to the diverse fauna and sloping terrain of the Appalachian Mountain Range, which begins in North Georgia.

“Not only are you descending to this historic park, but there are locations for retail, neighborhood, and building access,” says Murray, of how the portal meets its surroundings at multiple levels and places. “As it passes under the buildings it grows from their geometries.”

Connecting the Past and Present

The contagiously upbeat Irwin, who beams when I bring up Olson Kundig on a recent tour, unironically calls working with the firm “an unfathomable pleasure cruise of pleasure and delight.” He adds: “We all sort of talk in story and feeling. I felt like I found comrades there. It was just instant…‘yes, yes, totally!’”

He invites me to turn a crank sliding open a gargantuan glass and steel door fronting one of the project’s Beltline level spaces. “It invites a fierce curiosity in people,” he says, of this unique employment of industrial technology—one of Olson Kundig’s specialties. “You feel the echo of the past—that fascination with things that will never be built again.”

Irwin says that while most of his team is local, he intentionally hired a design architect from outside the city, who could take a fresh look at the place and deliver something unexpected. “They really understood this alchemy of how you preserve the gritty context while doing something resolutely new.”

And while he clearly savored the process of collaboration, he knew when to give his designers leeway. “I’ve always loved the idea of acting like a client that allows architects to actually do what they went to school to do. Which is to dream and think about human interface and culture and community and the effect that the built environment has on people. Kind of giving that dreaming part of a project the time and space to really incubate.”

The building’s robust, powder-coated aluminum fins, encircling its glass envelope and becoming denser in areas more exposed to sunlight, have become its signature. Slightly curved like airplane wings, they give the project an edgy, industrial character (Irwin likens their look to sci-fi movies like Blade Runner and Star Wars) and help block the hot Georgia sun while still letting tenants see clearly out. “I knew it would push the boundaries for Atlanta, which is known for its high-rise blue glass towers,” notes Irwin. “It feels of the place. This is the part of Atlanta that is young and gritty, and is really the center of re-urbanization in the city.”

The louvers, planned with intensive thermal and solar modeling, cut energy consumption by up to 20 percent, says Irwin—part of a sustainability strategy that includes a storm water management plan, massing that promotes natural breezes, and access to mass transit. The project is now aiming for LEED Gold certification.

Future Green’s landscape, extending from the building’s edges and stitching into the city’s rich tree canopy, delivers an equal edge. Often abutting concrete or steel planters and curbs, it’s moodier and more untamed than flowery or precious. A planned third tower, edged with a similar palette, will connect to the project via another bridge, creating a second portal down from the Beltline.

Inside the Raw and Refined Office Spaces

Inside, like much of Olson Kundig’s work, public spaces have a tactile roughness, a welcome break from the typical sterile corporate office setting. There is a lot of exposed concrete, timber, and metal, much of it locally sourced. “We used every opportunity to allow the core materials to serve as the finish, which lets the construction and craft shine through,” says firm principal and founder Tom Kundig. “We also left the detailing uncomplicated, minimally finished, and honest in its expression.” Adds Murray: “You can’t just keep adding materials. Concrete is beautiful—expose it when you can. Expose the tectonics of the buildings. Hopefully the bones of the building read as art.”

Office floors, measuring 13-feet-by-6-inches slab to slab, are open, with varying floor plate depths, allowing each tenant—which include Mailchimp, One Trust bank, WPP marketing, and shared workplace space Industrious—to freely carve out their own niches within. (Mailchimp’s offices, by Studio O+A—with their vibrant art program, varied “neighborhoods,” and flexible “labs” and “everything” spaces, has gotten most of the attention so far.) The hillside site also provides sweeping views of the city. It all seems to be working: the building is now 98 percent leased, says Irwin.

“If we can create all these great spaces, we create a place where people want to be,” he notes. “The portals, the hardscape, the stairs. All these things are in service of creating these interesting moments along the way. These fun elements of surprise and delight.” He adds: “We thought, ‘imagine if you actually enjoyed where you went to work every day?’”

Up next for Fourth Ward, in addition to Olson Kundig’s addition, are a collection of multifamily housing buildings by German architects Barkow Liebinger, sited on the development’s lower level. Per local inclusionary zoning rules, each will contain 10 percent affordable units. This is not, to be sure, affordable housing, but Irwin, who notes that this part of the Old Fourth Ward had essentially been an industrial wasteland (meaning no houses or local amenities had to be torn down) is confident that the Beltline—which traces of over 40 neighborhoods in the city—can accommodate change in a way the relatively focused High Line was not able to do. Each of Fourth Ward’s new pieces resume Irwin’s clear vision for new and vibrant design that is also sensitive and humane—something Irwin is carrying over with new projects in Nashville and Knoxville, Tennessee, which include work by Adjmi, S9, HKS, and local firm Smith Gee Studio.

“He fights for design while balancing budgets with the goal of creating better places that we all deserve,” says Kundig. “He’s the kind of developer I like to collaborate with and work alongside.” Adds Murray: “It’s an honor to be invited to a catalyst project like this. It’s good change. Visionary change.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

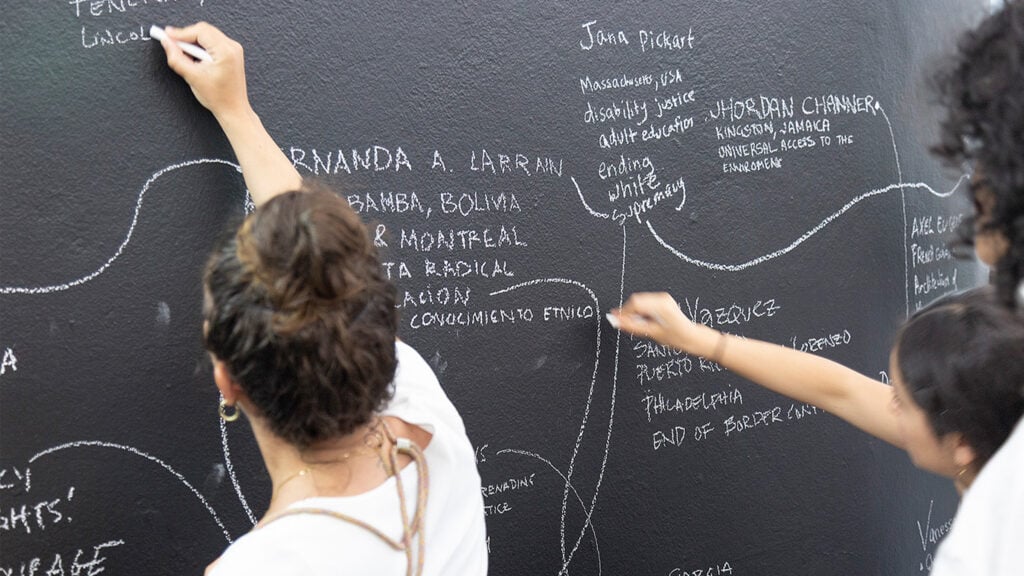

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.